“It’s sort of like a cheat code,” mused Kepa as Amalur hovered above their bed expectantly. “You know, in video games, there are times where they right combination of moves opens up an Easter egg.”

Maite turned to look at him. “You think this is all some kind of game?”

Kepa shrugged. “Not a game, exactly, but maybe it’s all some kind of program, some kind of Matrix-like virtual world. And I inadvertantly tapped into some parallel world.”

“I’ve seen some scientists argue that we are living in a simulation,” mused Maite. “I personally never believed it.”

Garuna rumbled in the back of Maite’s head. “This is no simulation. Of that I am sure.”

Maite repeated the AI’s words outloud for Kepa’s benefit. “Garuna says this isn’t a simulation.”

“Ok,” replied Kepa, “but then what does this mean?” He waved his hand in the general direction of Amalur. “She’s here.”

“Has she said anything since you conjured her? Besides ‘agur’?” asked Maite.

Kepa shook his head. “To be honest, I really haven’t tried to engage her. She barely appeared before you got home.”

Maite nodded as she turned to look at the dazzling form of Eguzki, her beauty almost painful to look at. “Why are you here?”

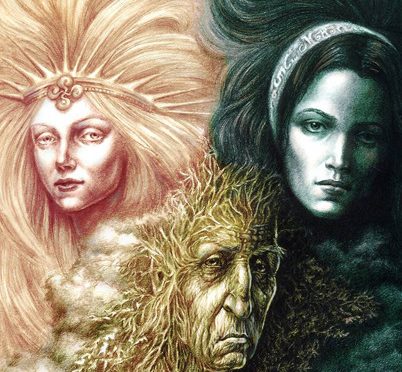

“I was summoned,” replied the unearthly figure as it slowly morphed into Ilargi, a visage that was equally as beautiful but easier to behold. At times, Maite couldn’t tell if there were three distinct beings or if they were all three present all the time and the one she saw was a matter of how her eye focused. It reminded her of those optical illusions where you saw either a duck or a rabbit depending on how you focused on the image.

“And?” asked Kepa. “What happens now?”

“Why was I summoned?” asked Amalur.

“No reason,” responded Kepa. “I summoned you by accident.”

“Then I will go,” replied Amalur as she began to fade.

“Ez! Wait!” exclaimed Maite.

The floating vision wavered for a moment, almost flickering, before it again solidified.

“Bai?” it asked.

Maite didn’t know what she should ask but she didn’t want Amalur to leave yet.

“Are you magic?” she asked.

“What is magic?” asked Amalur in reply. “There is no magic. There is simply the manipulation of energy.”

“Energy?” Maite sat, pondering for a moment. “Do you mean the conversion of energy from one type to another?”

“Energy is energy. There is no difference. Just how it is manifested.”

Maite turned to Kepa. “In physics, there is a theorem that all energy is conserved, that if you lose one type you gain another. Maybe magic is way to change that balance?”

“To break conservation?” asked Kepa.

“Not exactly,” replied Maite. “Maybe it is to control the flow of energy, to overcome entropy.”

“I’m not following,” interjected Kepa, looking thoroughly confused.

“Energy is always conserved, but entropy is always increasing. This means that energy is converted into forms that are less useful, like through friction, that increases entropy. Maybe magic lets us control or even reverse that loss. Think about it like this. Maybe magic lets us take energy from the air around us and turn it into more useful forms.”

“Like light and electricity?” asked Kepa.

Maite nodded. “Maybe.” She looked up at Amalur who appeared to her now in her earthly mother form. She was smiling at Maite.

If you get this post via email, the return-to address goes no where, so please write blas@buber.net if you want to get in touch with me.