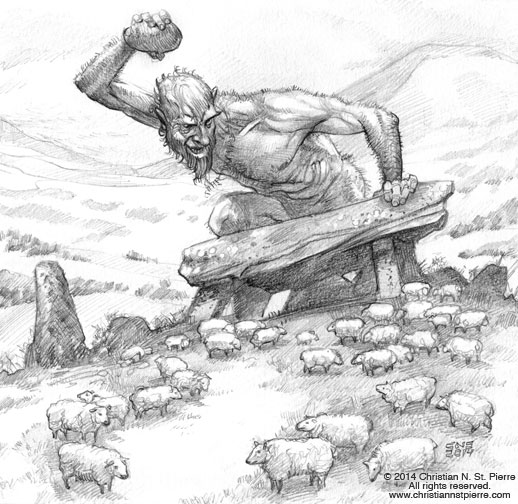

Anyone who has been to a Basque festival will recognize the rural theme of many Basque sports. Based on activities that would have occurred at the baserri, or farm house, Basque rural sports include wood chopping and sawing, bale lifting, and weight carrying. In fact, the Basque Government has identified 18 of these events in its Strategic Plan. Perhaps one of the most spectacular and popular of these events is harri jasotzea, or stone lifting. There are various variants of stone lifting, from lifting the biggest weight to lifting a smaller weight as many times as possible. In all cases, a successful lift consists of getting the stone to one’s shoulder.

- The world record for the heaviest lift is held by Mieltxo Saralegi, with a lift of 329 kilograms, or 725 pounds, a feat which took place in 2001 in Lekunberri. That is, he lifted rectangular rock off the ground and up to his shoulder that weighed over 700 pounds!

- Perhaps the most famous stone lifter is Iñaki Perurena, who held the previous record at 320 kilograms. He also held the record for the most lifts of a 100 kilogram stone: 1,700 times over the course of 9 hours. Iñaki has become a celebrity in the Basque Country, acting in the TV series Goenkale and writing bertsos.

- There is a stone, the Albizuri-Handi de Amezketa, that has become almost mythic in the history of Basque stone lifting. Weighing “only” 166.5 kilograms (367 pounds), it is a natural stone with a very irregular shape. While stories swirl that it was lifted in 1875 by José María Zuriarrain Galarza, the first confirmed lift occurred in 1947, by Santos Iriarte (known as Errekartetxo), who barely got it to his shoulder within the ten minute time limit. Aimar Irigoien lifted this stone in 2002, when he was only 16 years old.

- It wasn’t until stone lifter Bittor Zabala, who lifted between 1910 and 1945, came along that the stones were given standard dimensions and weights. Before that, stone lifters used whatever stones they wished, in whatever shape. Today, all of the stones (with the exception of special stones such as the Albizuru-Handi), are of specific size, weights, and dimensions.