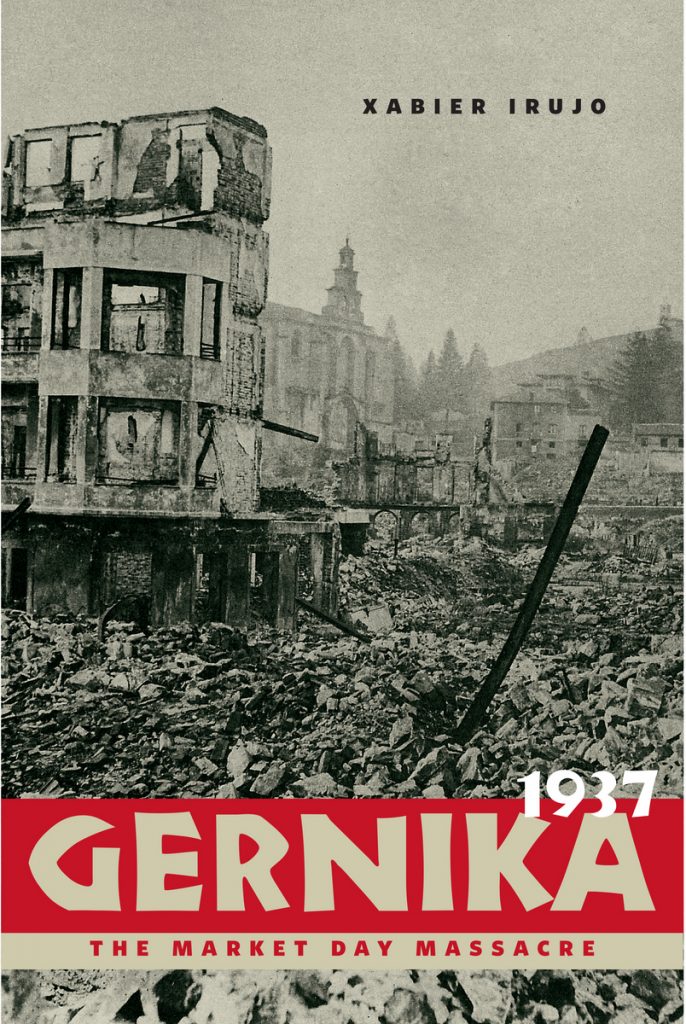

That Old Bilbao Moon is a complex and multifaceted book. Part memoir, part the history of a generation of Basques growing up in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, and part the story of the city of Bilbao and her people, Joseba Zulaika’s book takes a page from Dante and describes the history of the Basque Country via the lens of Bilbao. It is a wide ranging account, touching on the various underpriviledged and stigmatized classes of Bilbao’s people and the multitude of characters Zulaika has known that were connected, in one way or another, with the political and social upheaval that typified Euskadi in the later half of the 20th century. These were the Basques who formed the first Basque government and were subsequently exiled after Franco won the Spanish Civil War and, later, the young men and women who were disgruntled with the perceived failure of the earlier generation and turned to violence as a way of pursuing their goals.

That Old Bilbao Moon is a complex and multifaceted book. Part memoir, part the history of a generation of Basques growing up in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, and part the story of the city of Bilbao and her people, Joseba Zulaika’s book takes a page from Dante and describes the history of the Basque Country via the lens of Bilbao. It is a wide ranging account, touching on the various underpriviledged and stigmatized classes of Bilbao’s people and the multitude of characters Zulaika has known that were connected, in one way or another, with the political and social upheaval that typified Euskadi in the later half of the 20th century. These were the Basques who formed the first Basque government and were subsequently exiled after Franco won the Spanish Civil War and, later, the young men and women who were disgruntled with the perceived failure of the earlier generation and turned to violence as a way of pursuing their goals.

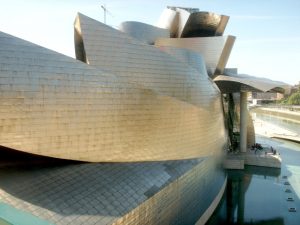

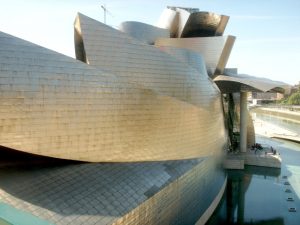

Zulaika’s tour of his generation and the forces that shaped it delves deep into the collective psyche of those men and women, often through philosophical discussions that, to be honest, were beyond me. But they provide a touch-stone for the environment in which the men and women that formed ETA and, in some cases, later found alternative paths to shape the future of their country. After the turmoil of a generation that rejected the politics of Aguirre and his contemporaries, modern Basque politics has begun a return to that approach that offers new paths for the future. As Bilbao has been reborn with the construction of the Guggenheim Museum and the so-called “Bilbao effect”, so to does the entirety of the Basque Country see new possibilities for a bright future.

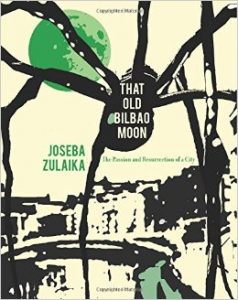

Joseba Zulaika kindly “sat down” (at his computer) and answered some questions I had about That Old Bilbao Moon.

Buber’s Basque Page: In your book, the history and struggle of the Basque Country, at least over the last 100 years, is embodied by Bilbao. Bilbao is an inferno in which the Basque identity is both forged and struggles. I’m curious as to what the other two Basque capitals, or for that matter, Pamplona, symbolize for you? Gipuzkoa has a higher percentage of Euskara speakers. Does Donostia have a different symbolism than Bilbao? Or is Bilbao special because of its history of the workers and its proximity to Gernika?

Joseba Zulaika: There are several reasons why I chose Bilbao for my book. Its historical proximity with and symbolic centrality of Gernika was one (and its relevance in the politics and history of art — Picasso — of the 20th century). The immediate reason was the establishment of the Guggenheim Museum and the international echo this had in the world of architecture, art and urbanism. I was writing in English for an international audience and the readers could have a reference about the Basques though the Guggenheim. And there were other reasons having to do with the recent history of the modern Basque Country, my generation’s struggles (euskera, ETA, nationalism, socialism), as well as autobiographical (I was in a convent there and studied in Deusto). Donostia or Gasteiz or Pamplona would share some of my generation’s themes and would have other historical and cultural references. Given my own interests and from the perspective of an international audience, Bilbao was the city.

Joseba Zulaika: There are several reasons why I chose Bilbao for my book. Its historical proximity with and symbolic centrality of Gernika was one (and its relevance in the politics and history of art — Picasso — of the 20th century). The immediate reason was the establishment of the Guggenheim Museum and the international echo this had in the world of architecture, art and urbanism. I was writing in English for an international audience and the readers could have a reference about the Basques though the Guggenheim. And there were other reasons having to do with the recent history of the modern Basque Country, my generation’s struggles (euskera, ETA, nationalism, socialism), as well as autobiographical (I was in a convent there and studied in Deusto). Donostia or Gasteiz or Pamplona would share some of my generation’s themes and would have other historical and cultural references. Given my own interests and from the perspective of an international audience, Bilbao was the city.

BBP: It seems to me that your generation delved deep into philosophy, something which I think isn’t happening so much anymore. Why was philosophy such an important factor in your generation’s lives as compared to today’s youth? Are you alarmed by a seemingly lack of interest in philosophy today?

Joseba Zulaika: I wouldn’t say we were necessarily more “philosophical” than other generations, but those of us who grew up in the 1960s in the Basque Country, many forced into an educational system controlled by religious orders, and in a convulse period of fighting dictatorship with revolutionary ideals, we were subject to conflicting worldviews and moralities that required thinking and philosophical arguments.

BBP: You mention how, in the last three generations, leisure has supplanted work as a source of satisfaction. Where do you see this going? Is this sustainable? Can a culture or economy that exists solely to consume survive?

Joseba Zulaika: On the one hand, there is a remarkable change regarding the value of work, leisure, consumption. On the other hand, as the majority of the youth can’t find work in the current Spanish economic slump, the search for employment is pushing many young people abroad, work being the only way for having a middle-class lifestyle.

BBP: As you write, your generation, the generation of ETA, rejected the politics of Aguirre as failed, as “impotent fathers” who had not fulfilled their promise of Basque nationalism. However, at the same time, you show how Aguirre and Prieto resolved, at least at a personal level, their political impasse and that modern politicians almost embrace the ideas of Aguirre. What do you think the true legacy of Aguirre and his generation is, post-ETA? Did Aguirre accomplish more than what was thought?

Joseba Zulaika: You could say that Aguirre and Prieto’s complicity has been repeated to some extent between Arnaldo Otegi and Jesus Egiguren in their search for overcoming the political impasse posed by ETA. Aguirre was an extraordinary man whose fate in a fascist Europe was tragic; he was a radical Christian and democrat who had to antagonize the Catholic Church and was abandoned by the European democracies. Some founders of ETA dismissed him as too accommodating with Spain, but his figure is unparalleled in the history of Basque nationalism and for many, including people on the nationalist left, he is the best guide for the kind of politics that is currently needed.

Joseba Zulaika: You could say that Aguirre and Prieto’s complicity has been repeated to some extent between Arnaldo Otegi and Jesus Egiguren in their search for overcoming the political impasse posed by ETA. Aguirre was an extraordinary man whose fate in a fascist Europe was tragic; he was a radical Christian and democrat who had to antagonize the Catholic Church and was abandoned by the European democracies. Some founders of ETA dismissed him as too accommodating with Spain, but his figure is unparalleled in the history of Basque nationalism and for many, including people on the nationalist left, he is the best guide for the kind of politics that is currently needed.

BBP: For your generation, the abondonment of Christianity is linked to the previous generation, their failure to establish an independent Euskadi, and a rejection of what they believed. However, it seems to me that atheism has risen across Europe and is not uniquely a Basque phenomenon. What other factors, broader than the Basque experience, have also pushed society in this direction?

Joseba Zulaika: Bilbao, like Basque society in general, has been a very Catholic city. But large pockets of atheism became a social reality at the turn of the 20th century with the creation of the socialist movement and the struggles of the working class. Many Basque nationalists stopped going to church as the result of the Catholic Church’s implication with Franco. Many of my generation, raised in seminaries, lost their religious faith as the result of getting involved in political protest. But this was nothing exclusively Basque of course; we were part of a larger European trend towards a more secular culture.

BBP: When you describe your discussion with the priest Bengoa, you highlight how he saw the break with ritual and ceremony as possibly beneficial, that breaking with religiousity might be good. That those who are most Christian are those that are the most anti-Christian in their language. It seems to me that the opposite is also often true, at least in the US. Those that profess their Christian values the most are often the least Christian, in some sense. How do you view this dichotomy?

BBP: When you describe your discussion with the priest Bengoa, you highlight how he saw the break with ritual and ceremony as possibly beneficial, that breaking with religiousity might be good. That those who are most Christian are those that are the most anti-Christian in their language. It seems to me that the opposite is also often true, at least in the US. Those that profess their Christian values the most are often the least Christian, in some sense. How do you view this dichotomy?

Joseba Zulaika: That was exactly how those radical Christians saw it: true religion is not about going to church and taking the sacraments, it is about helping the poor. The only God they accepted was the God of the poor. This led to the theology of liberation and to accepting ideas that might sound revolutionary. What they were doing was taking literally the Christ’s message that “what you do to one of these people, you do it to me.” Nothing was more deplorable to them than a Church that sided with the rich.

BBP: What is your view of the recent efforts by Scotland and Catalonia, and the ongoing efforts in Euskadi via Gure Esku Dago, for a voice? At least in Scotland, the people, in the end, rejected separating from the United Kingdom. If given the chance, will events turn out differently for the Basques and Catalans?

Joseba Zulaika: Scotland is fortunate to be in the United Kingdom and to be allowed to express the people’s will through a referendum. Basques and Catalans are simply not allowed such a referendum. This has been the losing struggle for Basques: the denied right to express their political will. The current situation in Catalonia is explosive, as they have decided to dismiss Spain’s prohibition to hold a referendum by framing the September 27 elections as “plebiscitary”—meaning that they will interpret a favorable vote to the parties seeking independence as a mandate to act and go ahead with secession.

BBP: Basque society today seems to be a series of polar opposites: Catholocism versus atheism, folk versus punk music, leisure versus the working poor, factories versus basseria. Is this simply a transition period from one time to the next, or is this inherent in Basque society?

Joseba Zulaika: Such polar opposites are primarily the creation of the analyst who has to make sense of the cultural and social complexity. But a century of sharp changes and transitions in every aspect of life has tended to create antagonistic oppositions that have made for turbulent times. This is not something uniquely Basque but, given the enormity of changes in concrete areas of culture and politics, the share among Basques for such polar opposites has been remarkable.

BBP: You mention that Aguirre finally became disillusioned when the US policy to contain communism meant siding with Franco’s government. In fact, the outcome of the Spanish Civil War was in large part a consequence of the West not wanting to get involved. Maybe it is foolish to play “what if”, but how do you think things might have turned out if the West had taken up the Republican and Basque causes?

Joseba Zulaika: Hitler and Mussolini sided openly with Franco. The democratic powers hypocritically adopted a policy of “neutrality.” Had they sided with the Republic, Franco would not have won. The U.S. was Aguirre’s only promised land of freedom where he found refuge—until even the U.S. sided with Franco in the early 1950s. The betrayals suffered by Aguirre would lead soon to ETA and another half a century of political turmoil for the Basques.

BBP: As you mention, you were one of those that was initially opposed to the idea of the Guggenheim in Bilbao. Later, however, you changed your mind. Was there a specific thing that changed your mind? What lessons do you think the Guggenheim effect has for other cities or nations? Is it a uniquely Basque phenomenon or something that has broader lessons?

BBP: As you mention, you were one of those that was initially opposed to the idea of the Guggenheim in Bilbao. Later, however, you changed your mind. Was there a specific thing that changed your mind? What lessons do you think the Guggenheim effect has for other cities or nations? Is it a uniquely Basque phenomenon or something that has broader lessons?

Joseba Zulaika: I changed my mind when I saw Gehry’s masterpiece of a building and the worldwide effect it had on architecture and art. Bilbao became the paradigm of a city transformed by iconic architecture and every city wanted to replicate the same “Bilbao effect.” I soon realized that the ironies I had seen in the deal between the Guggenheim and Bilbao were not the true story, but rather the power of the architecture and the will of Bilbao to transform itself into a new postindustrial city. Gehry says that the relationship with the client is the most important thing in the creation of his work and it says a lot about Bilbao and the Basques that he built his masterpiece there. There have been news about dozens of other similar Guggenheim projects worldwide but so far it has materialized only in Bilbao. The broader lesson is that a success story such as Bilbao doesn’t happen unless a city really believes in its future and is willing to do what it takes to make it happen.

BBP: What is next for Joseba Zulaika? What projects are you working on?

Joseba Zulaika: My next project is a book on Las Vegas. Lately I have been working mostly on two main areas of research — the transformation of cities, and drones and counterterrorism. Las Vegas combines both these interests, as drones are operated mostly from the Creech Air Force Base near Vegas. Besides, I have lived in Nevada close to three decades and this now my place.

Joseba Zulaika: My next project is a book on Las Vegas. Lately I have been working mostly on two main areas of research — the transformation of cities, and drones and counterterrorism. Las Vegas combines both these interests, as drones are operated mostly from the Creech Air Force Base near Vegas. Besides, I have lived in Nevada close to three decades and this now my place.

Share this / Partekatu hau:

Like this:

Like Loading...

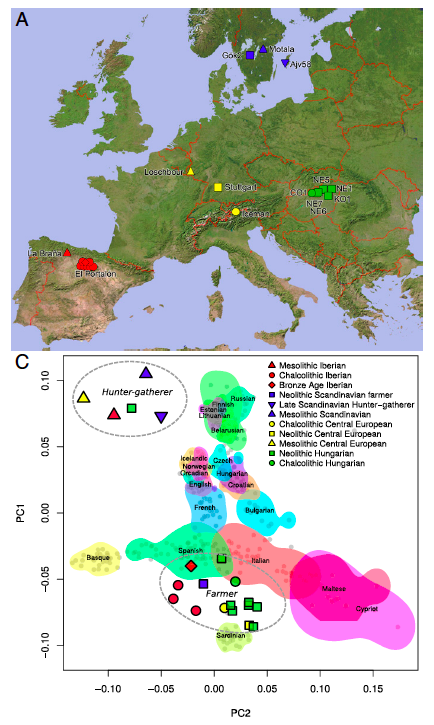

A few months back, a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) (Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques) caused quite the stir on the Basque portion of the internet. The paper examined the genetics of various populations, including Spanish, Italian, Russian, and, of course, Basque, and compared those genetics to determine where the Basques came from. Many reports had sensational headlines like Cave DNA unravels riddle of the Basque people, Ancient DNA cracks puzzle of Basque origins, Basques Linked to Ancient Iberian Farmers, Basque ancestors were farmers, Mystery of Basque origins solved, Science Seeks Answers to Riddles of the Mysterious Basques, and Unusual ‘relic language’ comes from small group of farmers isolated for thousands of years.

A few months back, a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) (Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques) caused quite the stir on the Basque portion of the internet. The paper examined the genetics of various populations, including Spanish, Italian, Russian, and, of course, Basque, and compared those genetics to determine where the Basques came from. Many reports had sensational headlines like Cave DNA unravels riddle of the Basque people, Ancient DNA cracks puzzle of Basque origins, Basques Linked to Ancient Iberian Farmers, Basque ancestors were farmers, Mystery of Basque origins solved, Science Seeks Answers to Riddles of the Mysterious Basques, and Unusual ‘relic language’ comes from small group of farmers isolated for thousands of years.

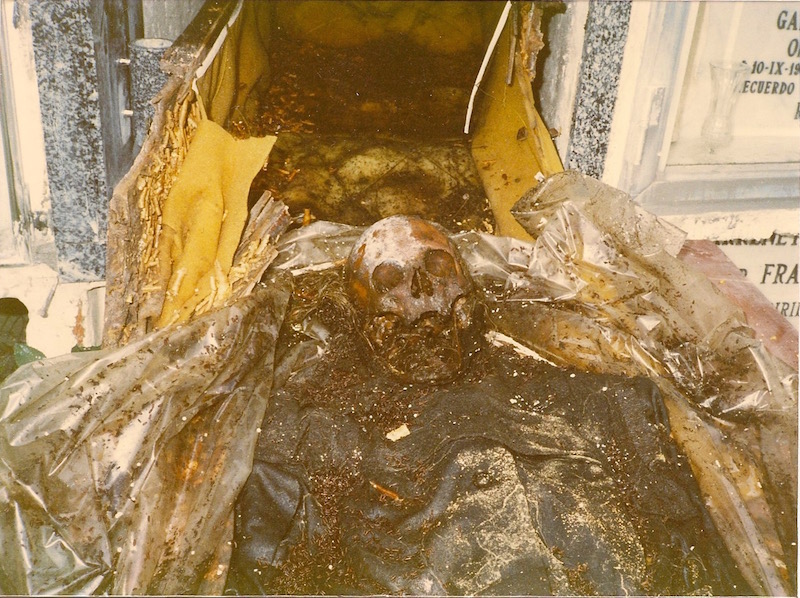

One of the most interesting and surreal experiences I had when I lived in the Basque Country during 1991-92 was when I went with my great uncle to the Gerrikaitz-Arbatzegi emetery. Cemeteries in the Basque Country are not as expansive as they are in the United States.

One of the most interesting and surreal experiences I had when I lived in the Basque Country during 1991-92 was when I went with my great uncle to the Gerrikaitz-Arbatzegi emetery. Cemeteries in the Basque Country are not as expansive as they are in the United States.

In addition, all of the people on the ship, including the cabin boys, were paid, at least in part, with oil.

In addition, all of the people on the ship, including the cabin boys, were paid, at least in part, with oil.

The Elhuyar brothers were born in

The Elhuyar brothers were born in