In memory of Dr. Emilia (Sarriugarte) Doyaga (Brooklyn, New York, 1925-2020).

This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, and the invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese Empire began an unstoppable expansionist military campaign across the Pacific against American, British and Dutch possessions in response to logistical support that, since 1941, the United States (USA) had given to the Republic of China in its war with the Japanese (the Second Sino-Japanese War began on July 7, 1937), and to the oil embargo by the Dutch and the British. In December 1941, Japan attacked British colonial territories in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, and Burma (today Myanmar). This opened a new military front in the global war, in which China, with the support of the United States and the Soviet Union, became a key player in curbing Japanese imperialist ambitions in Southeast Asia and which was baptized the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations. It was the great forgotten military theater of World War II (WWII). An estimated four million Chinese and Japanese soldiers perished as a result of the war, to which should be added between 10 and 25 million Chinese civilians who also died. The Second Sino-Japanese War was the greatest human tragedy in terms of the number of deaths in the entire Pacific War.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

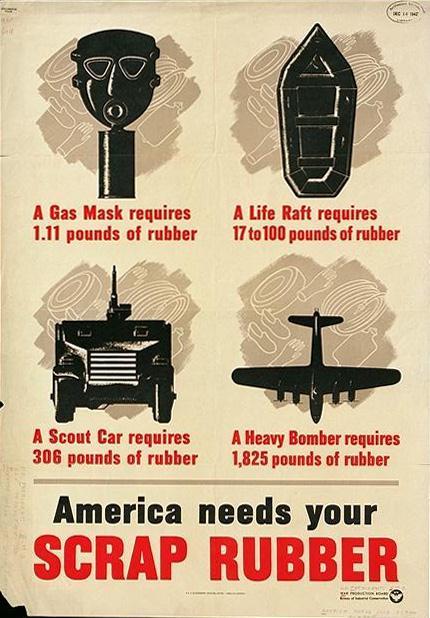

The invasion of Malaysia occurred on December 8 and was fully occupied by February 1942. From there, Japan launched another attack on the island of Singapore, south of the Malay Peninsula. On February 15, British troops from Singapore surrendered. In late December, Japan invaded Burma with 100,000 soldiers and nearly 700 aircraft. The British capitulated in April 1942. The invasion of Burma meant for Japan the capture of military supplies vital for the Allies and particularly for the United States, such as natural rubber. 90% of all natural rubber production grew within a 15-degree radius of Singapore. The response from the US government did not take long, which formed a consortium of rubber manufacturing companies with the objective of replacing natural rubber with synthetic ones. The multinational companies of today Firestone and later Goodyear would manufacture, in the spring of 1942, the first synthetic rubber in history.

Furthermore, Burma was a strategic target for Japan in its final victory against the Chinese resistance. Japan needed to cut off supplies to China, which were mainly carried out through the so-called Burma Road, built in 1938 with a length of 1,154 kilometers, that connected Yangon, to the south of Burma, and Kunming, in the Chinese province of Yunnan. Burma was the main country through which China supplied itself in its objective of defeating Japan since the invasion of 1937. The taking of Yangon in March 1942 meant control of the Burma Road and the end of allied supplies by land to China. (Japan had China isolated by sea since 1937.) The only allied solution at the time was to supply Chinese nationalists and US Air Force units by air from, initially, Dinjan in the province of Assam, India, to the city of Kunming — through the eastern tip of the Himalaya mountain range, baptized by the pilots as “hump” (with elevations above 4000 meters). The 800-kilometer-area route, also known as the Aluminum Trail, was inaugurated on April 8, 1942.

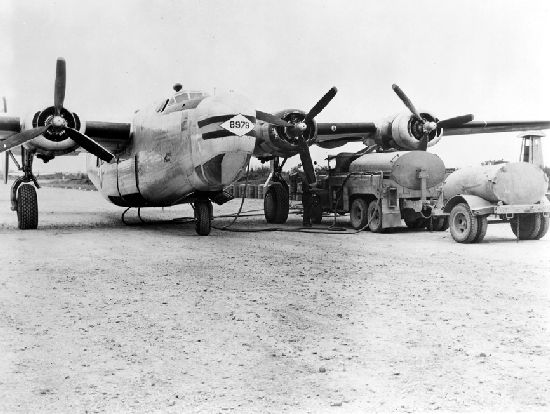

Among the children of immigrant Basques who flew over the Aluminum Trail, there were coincidentally four young people from Humboldt County, in the State of Nevada: Santiago Arriola Onandia and Joseph Malaxechevarria Plaza — both born in 1919 in the small rural town of Paradise Valley — John Montero Bidegaray, born in 1922 at the Leonard Creek family ranch, and Domingo Arangüena Bengoa, born in 1917 in Winnemucca. Santiago Arriola was recruited on October 17, 1941 before the United States entered the war. He joined the Air Force and received radio operator training at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. Promoted to Staff Sergeant, he departed for India under sealed orders from Sioux Falls (South Dakota) on an extraordinary journey that took him first to Greensboro (North Carolina), then to Miami Beach (Florida), where he caught a flight that would fly a route via Puerto Rico, Belim, Ascension Island, the Gold Coast of Africa (present Ghana), Khartoum, and Aden. His plane had engine problems and was forced to land in Madagascar, then continude on to Karachi, Barrackpore and, finally, the Kurmitola (Bengal) airfield, where he was assigned to the China-India Division of Transport Command. He flew the C-109 “Liberator Express” aircraft, modified as fuel transports, in what became known as the “Gas runs” from India to China. In late 1944 his unit was posted to the Shamshernagar Indian Airfield, where it remained until it was bombed by the Japanese in June 1945. By the end of his term of service he had crossed the Himalayas more than 100 times. At the end of the war, he was flown to Karachi, where he took a boat that would take him to New York. Demobilized in Fort Douglas, Utah, he arrived at his Paradise Valley home just in time for Christmas. He died in 1994.

Joseph Malaxechevarria (in the USA he was known as Joseph Echevarría) enlisted the same day of the attack on Pearl Harbor. He entered the Air Force and got a place at the technical training school at the Chanute Air Force Base (Illinois), where he graduated as a mechanic. He was sent to North Africa in late 1942 and then to Sicily, reaching the rank of Staff Sergeant. Later he was sent to India and China, where he had the opportunity to fly over the eastern end of the Himalayas. He received the Bronze Star for having successfully completed 150 hours of operational flight on transport aircraft in the months of January and February 1945 on the dangerous and difficult air routes between India and China, “while flying both day and night at high altitudes above impassable mountains which required courage and skill for long operating periods.” In the spring of 1945, he returned to the United States and was assigned to the fighter jet base in Indian Springs, Nevada, where he graduated. He passed away in 2010 at the age of 91.

An estimated 650,000 tons (81% of all supplies and people entering China) were transported by air between India and China throughout the war. By volume transported, it was the largest and most extended strategic airlift in the history of aviation until 1949. The human and aircraft cost was considerable, due to adverse weather conditions, extraordinary altitude, mechanical failures, the inexperience of pilots, and the occasional attacks by Japanese fighters. The pilots did not have a radar or a control tower and the radios were inadequate. Almost 1,700 crew and passengers and about 600 planes that made the India-China route were left for dead or missing. Among the latter is John Montero.

Montero was drafted on October 28, 1942 and entered the Air Force. He graduated as a gunner, joining the 45th Squadron of the 40th Bombardment Group, being part of the crew of the B-29 Superfortress “Stockett’s Rocket,” which was piloted by Captain Marvin M. Stockett. The B-29s began arriving at the base in Kuangchan (China) on April 24, 1944, but the first combat departure would not take place until June 5, 1944, from airfields in India. The objective was to bomb railway workshops in Bangkok (Thailand), losing up to five planes due to technical problems. The next mission was on June 15, 1944, targeting Japan, in what would be the first such attacks since the 1942 “Doolittle” Raid. Three B-29s were lost, including the plane that Sergeant Montero was flying in, who covered the gunner position on the left side. After taking off without incident from its base in Chakulia (India), “Stockett’s Rocket” disappeared without having been able to learn what its destination was, and its loss was officially reported. Everything indicates that they crashed when they could not pass the Himalayas. The news of Montero’s disappearance reached his hometown of Leonard Creek just a month later, and a mass was celebrated in his memory in the Catholic Church of Saint Paul in Winnemucca on July 9, 1944. The family was informed that he died during a routine flight from Chakulia (India) to Hsing-Ching (China) and that the last radio contact occurred when they were flying over Jorhat (India). Neither the plane nor, obviously, the bodies were ever found. Montero is memorialized in the Manila American Cemetery.

Domingo Arangüena was drafted on March 10, 1942. Destined for the Air Force, he trained as a mechanic and flight engineer for the B-25 medium bomber “Mitchell” at Mather Air Force Base in Sacramento, California. He then began a long journey that took him to North Africa, Egypt, Iran, Indochina, Burma and India, establishing his base of operations in Jorhat. Just after the war, he took part in search flights over the Himalayas, India, and Burma, where hundreds of planes had been lost, including John Montero’s B-29 “Stockett’s Rocket”. After returning to Winnemucca, he had the opportunity to speak with Montero’s father, Ramón, who asked him if he knew that country well and if it would be possible to go look for his son. He replied that there were planes searching and that he participated in many of those missions after the end of the war. About 1,200 crew members were happily rescued or returned to base on their own during the war. Arangüena passed away in 2004 at the age of 86.

Without the sacrifice and iron will of the air command and its personnel, it would not have been possible to distribute the resources necessary for the defense of China, which would have led to its military defeat. The success of the heroic operations over the Himalayas led Japan to keep more than a million soldiers and numerous resources on the Chinese front, without being able to dispose of them on the Pacific front, which greatly facilitated the final success of the Allies (1).

(1) Launis, Roger D., Scott, Beth F., Rainey, James C., y Hunt, Andrew W. (eds. 2000). The Hump Airlift Operation. The Logistics of War: A Historical perspective. Air Force Logistics Management Agency (U.S. Air Force). pp. 110–113

One thought on “Fighting Basques: The Aluminum Trail. Basques who flew over the Himalayas, 1942-1945”