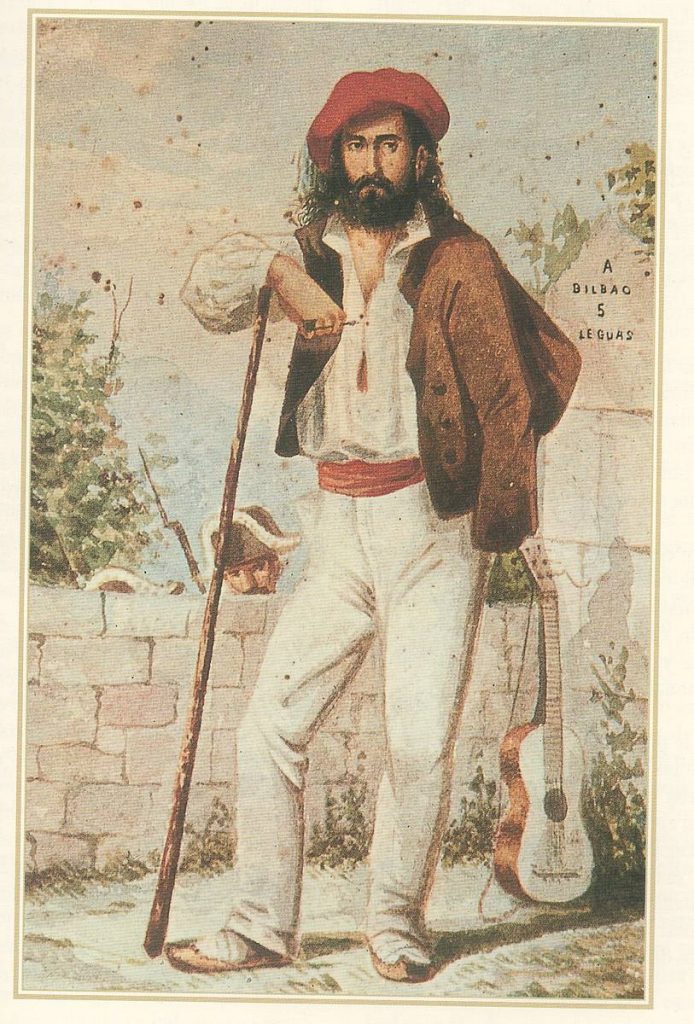

Soldier. Poet. Singer. Composer. Romanticist. Jose Mari Iparragirre was all of those things and more. A man out of time, he enjoyed great success and renown but never found a place he truly belonged. Even so, his most famous song, Gernikako Arbola, inspired generations of Basques.

- Iparragirre was born on August 12, 1820, in the village of Urretxu, in Gipuzkoa. His father, a merchant, pushed him towards of life of letters – Iparragirre was sent to Zerain to study Spanish with his uncle, then to Vitoria-Gasteiz when he was 11 to study Latin, possibly to prepare him for the priesthood. When he was 13, the family moved to Madrid where he entered a school run by the Jesuits.

- In 1833, the First Carlist War broke out and Iparragirre ran away to join the fight, with no other thought than “love for my countrymen.” He enlisted on the Carlist side, as part of the first battalion of Gipuzkoa. It seems this is when he took up the guitar, playing during free moments. He was injured first in the battle of Arrigorriaga and later in the Battle of Mendigorria, both in 1835, after which he became an attendant to Carlos, the claimant to the throne. Rejecting the Convention of Vergara that ended the war but saw a reduction in the strength of the fueros — the tradition of Basque home rule — and the final incorporation of the Basque Country into Spain, Iparragirre fled to France.

- Iparragirre became, in essence, a traveling minstrel. With guitar in hand, he wandered Europe, singing his songs wherever he could. In 1848, he joined the French Revolution of 1848, singing La Marseillaise — the French National Anthem — and inspiring the crowd. Once he took over, Napoleon III expelled Iparragirre as a subversive, after which he traveled through Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and, ultimately, England.

- In England, he met with a Spanish general who proposed a pardon. Iparragirre was given a pardon to return to Spain in 1853, and, it was during that year, in Madrid, that he first publicly performed, with Juan José Altuna, Gernikako Arbola. The song became the de facto Basque anthem, sung by Basques everywhere. The Spanish authorities became nervous and expelled him from Spain in 1855.

- This time, Iparragirre made his way across the Atlantic, to Argentina, with fellow Gipuzkoan, Anjela Kerexeta, in tow. In Argentina, they wed and had 8 children together. All the while, Iparragirre kept composing songs. In 1876, the last of the Basque fueros were abolished, leaving Iparragirre disconsolate for some time. He struggled, unable to make a living as a musician and with no mind for business. He told Anjela “It doesn’t matter if you have anything or not. Even the birds have nothing, and they live happily, flying in the sun.”

- In 1876, with the financial support of his countrymen, Iparragirre returned to the Basque Country, leaving his family behind in Argentina. He was honored by his country. He traveled, giving public recitals. Ultimately, he was given a pension by the provincial councils of Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, and Araba while that of Nafarroa gave him a donation. He died on April 6, 1881, in Itsaso, Gipuzkoa, after being caught in a storm and catching pneumonia.

Primary sources: Arozamena Ayala, Ainhoa. Iparraguirre Balerdi, José María. Enciclopedia Auñamendi. Available at: http://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/iparraguirre-balerdi-jose-maria/ar-69087/; Amagoia Gurrutxaga Uranga, Konbentzioen kontra, Berria; Wikipedia.