Guns, Germs, and Steel was one of the best books I’ve read, so I was very interested in reading Jared Diamond’s latest book, Collapse. Browsing the reviews at Amazon, they were very mixed, with some finding the book boring, a rush job, or saying nothing new. I guess I can see the last point, if I’d read more about the condition of the world’s environment. But I haven’t, so, for me, it was a real thought-provoking, eye-opening read. And I thought it was far from boring. I don’t know enough about the facts behind Diamond’s claims, so I can’t judge at all the veracity or the bias behind the statistics or claims Diamond makes. Even so, if even half of what he writes represents the real situation, then still the book is of great importance.

Guns, Germs, and Steel was one of the best books I’ve read, so I was very interested in reading Jared Diamond’s latest book, Collapse. Browsing the reviews at Amazon, they were very mixed, with some finding the book boring, a rush job, or saying nothing new. I guess I can see the last point, if I’d read more about the condition of the world’s environment. But I haven’t, so, for me, it was a real thought-provoking, eye-opening read. And I thought it was far from boring. I don’t know enough about the facts behind Diamond’s claims, so I can’t judge at all the veracity or the bias behind the statistics or claims Diamond makes. Even so, if even half of what he writes represents the real situation, then still the book is of great importance.

The basic theme of the book is that there are many examples of societies, both in the past and in modern times, that have failed. Diamond’s task is to try to understand why, and he has arrived at a five-point framework to consider a given society’s collapse:

- environmental damage by the society

- climate change

- hostile neighbors

- friendly trade partners

- the society’s response to its environmental problems

Not all of these factors contribute to any given society’s collapse, but, according to Diamond, at least one of these is a major contributing factor and for nearly all societies, the first one is often the most important. Diamond tries to demonstrate this by looking at various past and present societies that did fail, including Easter Island, the island of Henderson, the Anasazi, the Maya, Rawanda and Burundi, and the Greenland Norse, and some that overcame their problems and developed a sustainable society, such as New Guinea, Iceland, the Greenland Inuit, and Japan. As Diamond points out, some of the problems that faced some of these societies was essentially random luck, such as the quality of the land they settled. For example, the Greenland that the Norse encountered looked lush, like their native Norway, but the soil was not anywhere near as productive and that led to some of their struggles.

The point of all of this is to understand what led to the failure or eventual success of each society so that we can apply the underlying lessons to our modern world. Diamond illustrates those dangers by describing the current state of China, Australia and Montana, showing how ecological damage has affected the environment and, more important, the people and society of each. He concludes that failure is not a given, that societies at some point essentially choose to either fail or succeed.

One might wonder why they would ever “choose” to fail. To say that they choose to fail is a bit misleading. Rather, Diamond gives 4 reasons that they essentially do not end up fixing their problems:

- they fail to anticipate a problem before it arrives

- they fail to perceive a problem that has arisen

- they fail to try to solve a problem they do perceive

- they may try to solve the problem, but fail

The third point, that they don’t even try to solve a problem that they do know about, is the hardest to understand, but in truth it seems that societies do indeed just fail to act. Whether the choices involved in acting are too difficult, maybe involving abondoning core values or beliefs, or there are conflicting values, such as a profit motive. We are at a point where we will have to make these hard choices to confront problems facing us, choices that many of us will be reluctant to make.

Finally, Diamond describes 12 problems that are currently facing the world:

- the destruction of natural habitats, such as forests and wetlands

– Diamond claims that deforestation was one of or the primary reason for the collapse of each previous society he analyzes

– half of the world’s original forests have been converted to other uses and a quarter of what remains will be converted within the next 50 years - wild foods, a large fraction of protein for many of the world’s people, are disappearing, with many fisheries already having collapsed

- many species have gone extinct, decreasing the world’s biodiversity, upsetting the balance of many ecosystems

- farmland soil is being eroded at a much greater rate than it is being reformed, leading to the eventual ruination of that land; much other farmland is being destroyed by salinization

- the primary energy sources are fossil fuels, which are a limited, non-renewable resource

- most of the world’s freshwater is already being used, for irrigation, domestic and industrial use, or recreation, leaving very little for future expansion

- we are near the photosynthetic capacity of the planet; that is, the way that sunlight can be used for plant growth is finite and we are already using about half of that, even assuming plants are 100% efficient at capturing photons

- chemicals, either synthetic ones made by humans or natural ones that are made in extreme quantities by humans, are entering the environment; they have reached the furthest corners of the planet — the level of PCBs in the milk of Inuit mothers is at hazardous levels

- alien species, introduced either intentionally or unintentionally, are upsetting ecosystems around the world, destroying native species and making farming extremely difficult in some areas

- greenhouse gases and global warming

- the growth of the global human population

- finally, even more importantly, the impact per person on the environment is increasing

Upon reading his arguments, one realizes that the most alarming aspect of all of this is that these are problems today, in a world where the First World uses 32 times more resources per capita than the rest of the world, and the rest of the world is trying to catch up. The rest of the world sees how the First World lives and wants that standard of living. Getting there will mean that they too have a much higher per capita impact on the world, exacerbating all of the problems listed above. For example, if China alone, which is pushing hard to achieve First World standards of living, reaches the same level as the First World, the per capita environmental impact of the world will increase by a factor of 2. This is just if China reaches that level, and many of the other very populus countries are currently poor and working to get to First World standards.

All of this made me feel very depressed and pessimistic about the future. These are huge problems that will require huge efforts to fix, require huge changes in how we live. It seems to me that, to reach a sustainable lifestyle, people all around the world will have to compromise. The First World will have to realize that, even if the rest of the world stays poor, the lifestyle we have is unsustainable. We will have to settle for a lifestyle that is less affluent. At the same time, the rest of the world will have to realize that they cannot have the same standard of living the First World currently has, a harsh realization. This means hard choices on both sides, choices that it is not clear to me we will all make.

Diamond does end on one cautiously optimistic note. The problems we are facing are caused by us, meaning they can be fixed by us. Some of them will be difficult to fix even if we decide to do everything possible today. But, it can be done if we have the will. Whether we choose to do so will be the big question.

There is a lot in this book that I have failed to mention. I highly recommend this book and think it should be a topic of discussion in all classrooms in the country. We all have to acknowledge the problems facing us for there to be any chance that we can address them. That means we have to think beyond how we want to live and consider how we should live.

After reading this book, I am concerned about the world my daughter will live in. Hopefully, my generation will begin to act such that her generation has a better chance for a world in which the majority of humanity can live in both a sustainable and reasonably affluent manner.

On the way back home from Idaho, Lisa and I began listening to the audio version of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father. We aren’t done yet, so I’ll wait until giving my thoughts of his story, but there was one thing that jumped out at me.

On the way back home from Idaho, Lisa and I began listening to the audio version of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father. We aren’t done yet, so I’ll wait until giving my thoughts of his story, but there was one thing that jumped out at me. The

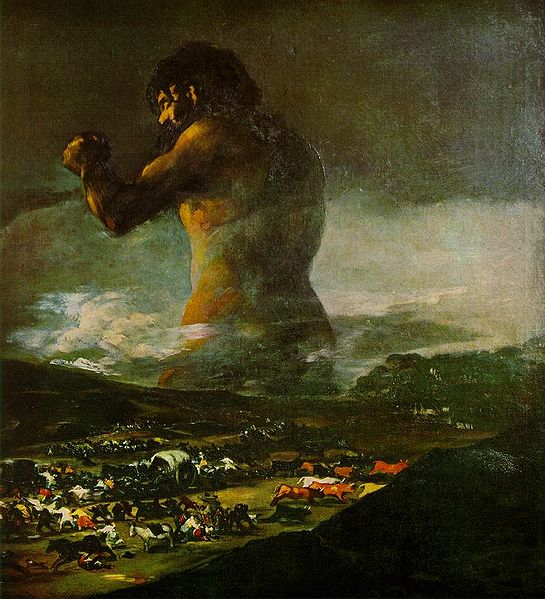

The  The second reason I like Goya is because I just plain like his art. Most of it I don’t appreciate much at all. It seems that half of art can only be appreciated in context. In the case of Goya, his paintings of the Spanish royal family, for example, seem to be lauded because he didn’t idealize his subjects and that was radical for his time. For me, it doesn’t seem all that exciting and I don’t really find all that much of interest in those paintings. However, his Black Paintings and many of his etchings are just plain fascinating. I was lucky enough to find a used copy of his complete etchings at Powell’s in Portland. Especially those dealing with the Spanish war with Napoleon I find very interesting. Goya depictions of humanity’s dark side are, in my mind, still unparalleled.

The second reason I like Goya is because I just plain like his art. Most of it I don’t appreciate much at all. It seems that half of art can only be appreciated in context. In the case of Goya, his paintings of the Spanish royal family, for example, seem to be lauded because he didn’t idealize his subjects and that was radical for his time. For me, it doesn’t seem all that exciting and I don’t really find all that much of interest in those paintings. However, his Black Paintings and many of his etchings are just plain fascinating. I was lucky enough to find a used copy of his complete etchings at Powell’s in Portland. Especially those dealing with the Spanish war with Napoleon I find very interesting. Goya depictions of humanity’s dark side are, in my mind, still unparalleled. the context of Spanish society of the time. That is, we get to know Goya as much through his interactions with Spanish royalty as through his own deeds. Connell goes on a number of tangents dealing with important Spaniards of the time and their goings on. We learn a lot about the sexual conduct of certain powerful women of the time, partially because these women, including the Queen of Spain, determined so much in the life of people like Goya. I think part of the reason these women feature so prominently, though, is because of the titillation factor.

the context of Spanish society of the time. That is, we get to know Goya as much through his interactions with Spanish royalty as through his own deeds. Connell goes on a number of tangents dealing with important Spaniards of the time and their goings on. We learn a lot about the sexual conduct of certain powerful women of the time, partially because these women, including the Queen of Spain, determined so much in the life of people like Goya. I think part of the reason these women feature so prominently, though, is because of the titillation factor. This is the first book specifically on Goya I have read and it may be that part of the reason that Connell digresses on so many other people is because there just isn’t that much known about Goya himself. I just don’t know. For whatever reason, because of this style, we learn a bit less about Goya the man and a good deal about the Spain in which he resided, the Spain that shaped him and his art. We learn about the foibles of the nobility, the misery of the peasants, and the horrors of war. Thus, as a book on Goya, it maybe leaves a little to be desired. But, as both an account of Spain in the later 1700s and as an entertaining romp through history in its own right, this is an excellent book. I highly recommend it to any Spanish history buff.

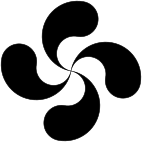

This is the first book specifically on Goya I have read and it may be that part of the reason that Connell digresses on so many other people is because there just isn’t that much known about Goya himself. I just don’t know. For whatever reason, because of this style, we learn a bit less about Goya the man and a good deal about the Spain in which he resided, the Spain that shaped him and his art. We learn about the foibles of the nobility, the misery of the peasants, and the horrors of war. Thus, as a book on Goya, it maybe leaves a little to be desired. But, as both an account of Spain in the later 1700s and as an entertaining romp through history in its own right, this is an excellent book. I highly recommend it to any Spanish history buff. The lauburu, literally “four heads” in Basque, is a ubiquitous and ancient Basque symbol. You see it all over the place in the Basque Country and has become a national identifying symbol. It has obvious connections to other four-armed symbols, such as the swastika, a symbol that appears in many parts of the world, including India and North America.

The lauburu, literally “four heads” in Basque, is a ubiquitous and ancient Basque symbol. You see it all over the place in the Basque Country and has become a national identifying symbol. It has obvious connections to other four-armed symbols, such as the swastika, a symbol that appears in many parts of the world, including India and North America.