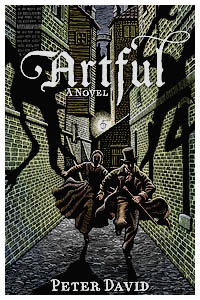

It seems the vampire and zombie thing is being done to death and Artful, by renowned comic book writer Peter David, is yet another entry into the mix. Focusing on vampires, it takes place in Oliver Twist’s world, shortly after the end of Dicken’s novel. Thus, already, it makes for a somewhat novel take on the whole vampire schtick. And, as the introduction makes clear, this isn’t a world full of emo vampires, struggling with their humanity. As the narrator states:

It seems the vampire and zombie thing is being done to death and Artful, by renowned comic book writer Peter David, is yet another entry into the mix. Focusing on vampires, it takes place in Oliver Twist’s world, shortly after the end of Dicken’s novel. Thus, already, it makes for a somewhat novel take on the whole vampire schtick. And, as the introduction makes clear, this isn’t a world full of emo vampires, struggling with their humanity. As the narrator states:

Watch some television programs, or read some books in which vampyres are heroic and charming and sparkle in the daylight, and then return here and brace yourself for a return to a time that vampyres were things that went bump in the night.

These vampires here are down right evil, with the goal of subjugating the human race, or at least grabbing a good share of power.

Peter David is known in the comic book world for taking characters that have been cast aside and breathing new life into them. Here, he does something similar to the Artful Dodger, the hero of this novel, though certainly not of Dicken’s original take. Artful finds himself in a world of vampires and intrigue where what he once took for granted is no longer what it seems. Artful befriends a young woman, lost on the streets, and their adventure into the world of the vampires begins. Along the way, the son of vampire hunter Van Helsing, a young boy who is very mature for his age, joins the adventure and even Oliver himself makes an appearance.

David’s penchant for dialog shines, which some memorable lines such as:

— bloodsucking monsters known as tax collectors already existed

— Only in death do worthless people have worth.

— the average person, of whom there is an insufferable number in the world

— lack of attention from God is not necessarily a bad thing, as the former residents of Sodom, Gomorrah, and the entirety of the Earth prior to Noah’s construction of an ark would have been able to attest.

— [regarding prostitutes] With how much respect do people treat slabs of beef? Beef is pounded, sates the appetite, and is extended no particular consideration beyond that. The sad truth is that oftentimes the ladies are seen as similar objects in that they are pounded in a variety of ways for the purpose of satisfying certain appetites, albeit unwholesome ones, and the remains are left behind for someone else to worry about.

There is a lot of commentary on society and politics sprinkled through out the novel, mostly from the point of view of a street urchin like Artful.

The novel is great fun, traipsing through Victorian London with numerous references to other literature set in the same time. Artful encounters the Baker Street Boys and even some more historical characters from the time. The action is fast paced, the characterization vibrant, and the plot has enough twists and turns to keep you engaged.