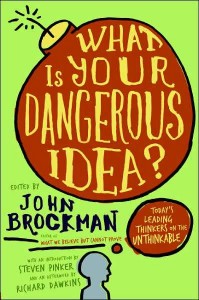

In a series of books, one each year, John Brockman asks the contributors and members of Edge.org a question. The goal is to foster exchange, to provoke thinking, and to stir debate. I thought I’d give my own answers to each question.

In What is Your Dangerous Idea?, John Brockman asked exactly that: “What is your dangerous idea?” Well, I have two.

The American Dream is a Fraud.

I’ve touched on this before. One of the defining tenants of American society is that anyone can make it, can be a success, if only they work hard. I have serious doubts that hard work is the most important criterion for success in American (with inheritance, skill, perseverance, and dumb luck likely all being more important), but let’s set that aside for the moment. Let’s assume that hard work, and hard work alone, will get you to the top. It’s a nice thought, and a nice ideal, but it simply can’t be true. There isn’t enough room at the top for everyone. Someone has to do those jobs near the bottom of the economic ladder, those jobs no one chooses to do, but must be done for society and the economy to function. Jobs that don’t pay well. The bottom rungs of the economic ladder must be occupied by someone, regardless of how hard everyone works. That is, even if everyone worked hard, the vast majority have to fail for the system to work. The top need the bottom to exist. Thus, the system has to be rigged to ensure that the bottom exists.

As a consequence, it simply can’t be true that all one needs is to work hard. Sure, some will work hard and rise above their “humble beginnings,” but we all can’t. Most of us won’t, regardless of how hard we work. If the majority of us are able to move up the ladder, we must bring in new people who are willing to exist at the bottom, for whatever reason.

The only way I can see that the American Dream can be a reality for the vast majority of Americans is for us to develop the technology to automate all of those jobs at the lowest economic rungs. Possibly then, we won’t need people to do them and the system will have the freedom to allow most or maybe even all of us to move up and realize the American Dream. But, until that happens, I fear that most of will have to settle for the hope of the American Dream for their children.

Behavior can be Predicted and Controlled.

It seems that, as we learn more about how the brain functions, we are learning more and more that many behaviors are a consequence of the structure and chemistry of the brain. Much of what defines each of us is based on genetic factors and our predilections are often a function of how our brains are wired, out of our direct control. If true, this has enormous implications for our place in society.

Imagine if each of our brains can be mapped to such a degree that we can place high probabilities of us behaving in certain ways. And imagine if this could be done when we are infants. That is, consider a world in which an infant, not long in this world, can have his or her brain mapped and the propensity for unsocial behavior determined. Behavior, for example, such as tendency to be violent or a psychopath or a sociopath. What should we do with such capabilities and knowledge? Should we use it to determine the likelihood of each and every individual’s probability to be a damaging member of society? And, if we can, what should we do to those people? Should we continuously monitor them in the hope of preventing them from harming anyone? Should we abscond them away to ensure they don’t?

Now imagine we take the scenario a bit further. Imagine we have the ability to change behavior, through chemistry. We do this already to some extent, with ADHD and other behaviors deemed undesirable. What if we could use chemicals, possibly forcibly given, to turn off that part of the brain that drives pedophiles? Or murders? What if we could alter the brain chemistry of individuals determined to be a danger to society to remove that danger? That is, what if we could stop these people from doing any harm, by changing them before they were ever able to do any harm? If we could identify the Jeffery Dahmers and Adolf Hitlers of the world long before they became those monsters, should we? And what should we do about it?

There are many ethical questions that arise from such a scenario, including the right of society to so drastically interfere with the rights of any given individual who has done nothing wrong, but has a brain that strongly indicates they will. Further, there will be those who want to use such power for more nefarious purposes, such as eliminating people with behaviors that aren’t dangerous but are deemed unacceptable (for example, homosexuality) or maybe dangerous to the regime (such as a proclivity to question authority).

I think we will soon have the ability to both determine who might be prone to dangerous behavior and then modify them so they don’t. We will soon have to answer questions about what we do with that ability.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The conceit of stories like the X-Men is that there are people who are born that are different than the rest of us, and that difference makes them both special as well as a potential threat. In the case of the X-Men, they have extraordinary powers — shooting eye beams, controlling the weather, walking through walls, turning into metal — that give them enormous advantages over the rest of humanity. In some ways, that is the same conceit of Marcus Sakey’s Brilliance, though here it is treated in a much more subtle and realistic manner.

The conceit of stories like the X-Men is that there are people who are born that are different than the rest of us, and that difference makes them both special as well as a potential threat. In the case of the X-Men, they have extraordinary powers — shooting eye beams, controlling the weather, walking through walls, turning into metal — that give them enormous advantages over the rest of humanity. In some ways, that is the same conceit of Marcus Sakey’s Brilliance, though here it is treated in a much more subtle and realistic manner.