After Peter Parker is bitten by that radioactive spider, the first lesson he learns is that “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Society is constantly having to relearn this lesson, especially as technological advances give us more and more power in new and different realms. Harnessing the power of the atom has given us both nuclear energy and nuclear weapons. Medical advances have allowed us to extend life, even create life such as so-called test tube babies. Genetically modified food offers great hope to help feed the world but also the dangers of Franken-food. And the internet has revolutionized how we communicate, both for good and bad.

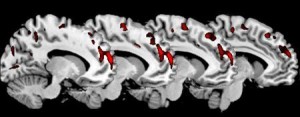

One of the next big frontiers of science is neuroscience, the science of the human brain. By understanding how the brain works, we are understanding more about how we function, why we behave the way we do, and what differentiates each of us. We are now at the point that we can, using a brain scan, know if we are looking at the brain of a psychopath or a normal person. If you think about it, this is tremendous power. This is probably as close as we will ever come to Minority Report, being able to tell if someone is likely a criminal before they ever do anything.

One of the next big frontiers of science is neuroscience, the science of the human brain. By understanding how the brain works, we are understanding more about how we function, why we behave the way we do, and what differentiates each of us. We are now at the point that we can, using a brain scan, know if we are looking at the brain of a psychopath or a normal person. If you think about it, this is tremendous power. This is probably as close as we will ever come to Minority Report, being able to tell if someone is likely a criminal before they ever do anything.

Think about it. If a psychopaths brain is truly different from the rest, a brain scan will identify who is a psychopath before they do anything to harm anyone. We would know if they have the potential for becoming a psychopath. And we might even be able to do that scan when they are a child.

Think about it. If a psychopaths brain is truly different from the rest, a brain scan will identify who is a psychopath before they do anything to harm anyone. We would know if they have the potential for becoming a psychopath. And we might even be able to do that scan when they are a child.

Given that we could, in principle, do such a scan and identify potential psychopaths long before they become psychopathic, what should we do with that power? Should we scan everyone’s brains, and closely watch those that are likely to become psychopaths? This seems a huge infringement on personal liberty, but if it prevented the type of massacre that occurred in Norway, might it be worth it?

On the flip side, if psychopaths and other sociopaths truly have a different brain structure, how much of their actions are they really responsible for? If it is all brain chemistry controlled by genetics, should we all be thankful we have normal brains? Should we try to identify these people so we can find some way to treat them so they can lead normal lives?

And, finally, consider the fact that there is a very fine line between psychopathy and genius. Studies suggest many of the top CEOs exhibit psychopathic traits. If we somehow controlled the behavior of presumed psychopaths, would we be impacting other areas of society, including business and politics?

And, finally, consider the fact that there is a very fine line between psychopathy and genius. Studies suggest many of the top CEOs exhibit psychopathic traits. If we somehow controlled the behavior of presumed psychopaths, would we be impacting other areas of society, including business and politics?

I have lots of questions and no answers. I think these types of questions will soon confront us. And technology is advancing at a pace that is much faster than at least our political and legal systems can keep up with. We will be faced with a future where people who barely understand the implications of the science, much less the science itself, are placed in a position of trying to address these questions. I think the sooner society as a whole dwells on them, the better able we will be able to deal with them.