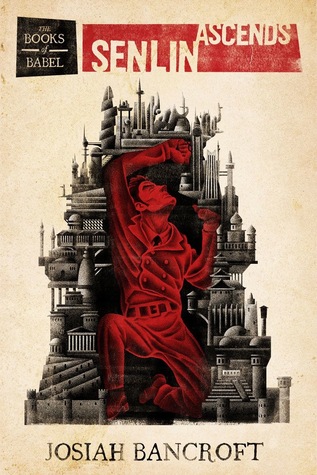

The premise of Senlin Ascends, by Josiah Bancroft, is… odd. In Thomas Senlin’s world, which is somehow modeled on ours but is just enough different, there is a tower of Babel, a monument to some powerful and previous civilization that is at the center of Senlin’s dreams. The tower is the epitome of knowledge and Senlin, a school teacher, desires more than anything to bask in its glory. When he gets married, this is where he takes his bride for their honeymoon.

However, the tower is nothing like he imagined, like the guide books he devoured described. The book describes his journey in the tower, which feels so much like an odd adventure quest. As Senlin learns about the tower, he learns about himself as well, and grows from the timid school teacher into something more.

So, the plot really revolves around Senlin understanding the true nature of the tower and encountering various characters and executing various tasks, almost like a strange role playing game. The tower would be an excellent setting for such an adventure. It almost reminds me of these roleplaying adventures I led when I was a kid, where we had a random dungeon in which each room was a random environment or place. The tower almost feels the same. As Bancroft writes in an interview at the end, he wrote this book because “I liked to be surprised and delighted, liked to gasp and laugh, and wanted to share the whole mad experience with someone else.” The tower is the perfect place to share such experiences. Anything goes, and what happens in one level doesn’t have to have anything to do with the next level.

But, what makes the story stand out isn’t so much the plot but the characters and the setting. The tower is its own character, with each level a completely different setting with its own set of people and activities, essentially a world unto itself.

One of the first things Senlin encounters after making it inside the tower is a beer-go-round, where people have to pedal, making the entire thing spin, until enough energy is pumped into the machine to make beer spray everywhere.

As Senlin makes his way through his journey of discovery, of both the tower and himself, he meets a number of characters that challenge his world view. “Never let a rigid itinerary discourage you from an unexpected adventure,” they tell him, and “I’d rather be a nothing at the center of everything than a puffed-up somebody at the edge of it all.” He meets powerful people that pull the strings, at least in their part of the tower. These people provide him lessons in power: “The powerful never trust. They respect and are respected. Trust is a weak bond, and it is for the weak.” and “Powerful mean fail just as much, if not more often, than the failures. The exceptional thing is that they admit it; they take and hold up their failures. They claim their disappointments; they move on!” Each person Senlin encounters teaches him something new, provide him a new perspective on life and the world that he had never considered.

This is the first in The Books of Babel trilogy. I’m certainly looking forward to what Senlin finds as he keeps climbing the tower.