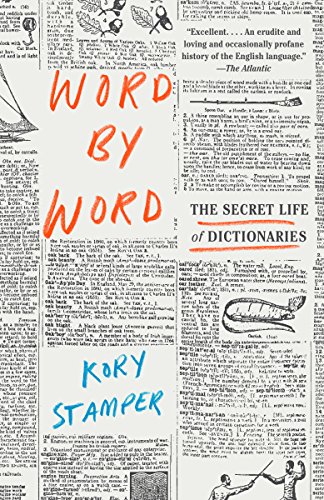

Kory Stamper is a lexicographer used to work for Merriam-Webster, writing dictionaries. Word by Word is, in some sense, a memoir of her time there, from the point of view of some of the more interesting and challenging words she encountered. It’s both a description of what it means to be a writer of dictionaries, both now and in the past, as well as a vivid reminder of how language evolves. If there is nothing else to take from Stamper, it’s that language changes, that words come and go, and that there is no “correct” way of writing.

Stamper sprinkles Word by Word with stories of words the confound dictionary writers and the dictionary writers themselves. There are brief historical asides on the first dictionaries and how they changed over the years. Stamper loves English and her love shines through in her relationships with words. She throws out quite a few that caught my eye:

- snollygoster: an unprincipled or shrewd person

- Why do we call practical and unflappable people “phlegmatic”? Because we used to believe that they were unexcitable because they had an overabundance of phlegm in them.

- “GI” (originally “galvanized iron,” if you can believe it, but misconstrued by soldiers and others as “government issue”)

- “snafu” and “fubar” (“situation normal: all fucked up” and “fucked up beyond all recognition,” brought to you by government bureaucracy)

- Who thought that “pumpernickel” was a good name for a dark rye bread? Because when you trace the word back to its German origins, you find it means “fart goblin”

- borborygmus: intestinal rumbling caused by moving gas

A key message Stamper emphasizes multiple times: Dictionaries are not meant to be prescriptive, to tell us how to use English. Rather, dictionaries are there to record how the language is actually used. They don’t tell us what is right or wrong, but rather what is actually done. “We are just observers, and the goal is to describe, as accurately as possible, as much of the language as we can.”

As alluded to above, the parts I enjoyed the most are where Stamper rails against the so-called grammar Nazis that tell us how words have to be used. A few examples:

- “Good” has been used for almost a thousand years as an adverb, even though usage commentators and peevers have condemned this use.

- The fact is that many of the things that are presented to us as rules are really just the of-the-moment preferences of people who have had the opportunity to get their opinions published and whose opinions end up being reinforced and repeated down the ages as Truth.

- Standard English as it is presented by grammarians and pedants is a dialect that is based on a mostly fictional, static, and Platonic ideal of usage.

- People rarely think of English as a cumulative thing: they might be aware of new coinages that they don’t like, but they view those as recent incursions into the fixed territory they think of as “English,” which was, is, and shall be evermore.

One interesting bit is when Stamper goes into pronunciation, using the word “nuclear” as an example. I’m a bit sensitive to this one as people who say “nucular” are often ridiculed in my field (of nuclear materials) and I’m always a bit fearful that I say it that way. George Bush got a lot of flak when he pronounced it “nucular,” however Stamper points out that the earliest print records of that spelling come from people in the military, government, and nuclear sciences. She notes that Jimmy Carter pronounced nuclear as “nucular” and goes on to say “Jimmy Carter spent his time in the U.S. Navy working on… nuclear submarines… and actually [was] lowered into a nuclear reactor core that had melted down in order to dismantle it. To my mind, he has earned the right to pronounce ‘nuclear’ however he damned well pleases.“

As someone who writes a lot, both for work and pleasure, I found Stamper’s view of the language refreshing. She doesn’t advocate for a right way of doing things, but acknowledges and indeed glories in the fact that English (and all languages, except dead ones) evolve. Every generation seems to think that the language is going to hell, that the kids don’t respect the language of their fathers and mothers. The fact is, neither did they. And that is what makes language so interesting.