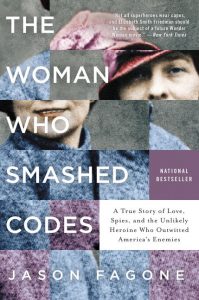

The true makers of history are often hidden from us, either owners of softer voices or casualties of the rhetoric of louder glory-seekers. More often than not, those lost voices below to women and that is the case for Elizebeth Smith Friedman, one of the first people to develop a science for code-breaking and a key, if not the key, figure in the development of the US’s intelligence services. As the author of her story, The Woman Who Smashed Codes, Jason Fagone writes, “It’s not quite true that history is written by the winners. It’s written by the best publicists on the winning team.”

The true makers of history are often hidden from us, either owners of softer voices or casualties of the rhetoric of louder glory-seekers. More often than not, those lost voices below to women and that is the case for Elizebeth Smith Friedman, one of the first people to develop a science for code-breaking and a key, if not the key, figure in the development of the US’s intelligence services. As the author of her story, The Woman Who Smashed Codes, Jason Fagone writes, “It’s not quite true that history is written by the winners. It’s written by the best publicists on the winning team.”

The story of her and her husband, a leading code breaker in his own right, is fascinating, not only for the development of code-breaking as a science and their contributions to more than one war, but also because of the odd and eccentric characters that populate Elizebeth’s life. Her husband, William, was perpetually on the edge of a nervous breakdown, in part due to the extremely long hours both Friedmans put in service to the US government. Maybe most fascinating of all was Elizebeth’s first patron, George Fabyan, who created a compound outside of Chicago — the Riverbank Laboratories — which was a private laboratory researching a multitude of topics, some scientifically sound and others very much of the crack-pot variety. It was at Riverbank that Elizebeth first encounter cryptography and her future husband William. Riverbank was full of would-be scientists, studying a range of topics from hidden messages in Shakespeare’s plays to acoustics, for which it still exists. The compound raised all its own animals and grew much of its own crops for food.

During World War I, there was a dearth of people who understood encryption, much less could decipher the messages of the enemy. William and Elizebeth demonstrated their abilities and developed a true scientific approach to the problem. Both Friedmans had an uncanny knack of seeing patterns in data, at a time when computers weren’t available to help with the task. But, at the same time, one had to discern real patterns and not ones made up by their own brain. As Fagone writes, “Humans are so good at seeing patterns that we are often able to see patterns even when they aren’t really there” and “One way of thinking about science is that it’s a check against the natural human tendency to see patterns that might not be there.” Seeing and identifying real patterns was the first criterion for breaking a code.

During the time the Friedmans were developing the science of cryptography and creating the profession of the cryptanalyst (“a person who analyzes and reads secret communications without the knowledge of the system used”), the world was changing at an incredible pace. Radio communications meant that agents could speak to each other across the globe, without the need to exchange paper. The atom bomb was being developed. Politics were changing too. J. Edgar Hoover was accumulating power in the FBI and was at odds with the military in the use of cryptography. What do you do when you break a code? As was highlighted in the movie The Imitation Game about the life of another famous cryptanalyst, Alan Turing, if you act on the intelligence from the broken code, you reveal the fact that the code is broken to the enemy, leading them to change the code and breaking that stream of intelligence. Her husband called this dilemma “cryptologic schizophrenia.” It is a no-win situation for the cryptanalyst, especially since human lives were often at stake. The FBI was chasing sensationalist news rather than maximizing the benefit to the nation of the broken codes.

During the time the Friedmans were developing the science of cryptography and creating the profession of the cryptanalyst (“a person who analyzes and reads secret communications without the knowledge of the system used”), the world was changing at an incredible pace. Radio communications meant that agents could speak to each other across the globe, without the need to exchange paper. The atom bomb was being developed. Politics were changing too. J. Edgar Hoover was accumulating power in the FBI and was at odds with the military in the use of cryptography. What do you do when you break a code? As was highlighted in the movie The Imitation Game about the life of another famous cryptanalyst, Alan Turing, if you act on the intelligence from the broken code, you reveal the fact that the code is broken to the enemy, leading them to change the code and breaking that stream of intelligence. Her husband called this dilemma “cryptologic schizophrenia.” It is a no-win situation for the cryptanalyst, especially since human lives were often at stake. The FBI was chasing sensationalist news rather than maximizing the benefit to the nation of the broken codes.

The story follows Elizebeth’s career from a scientist building the beginnings of a new scientific field to her work for the government, where she ultimately found a home with the US Navy, where she tracked Nazi spies in South America. She also worked for the US Treasury, intercepting the messages of crime lords working within the US. Throughout it all, Elizebeth simply did her work, serving her country, either not willing or even able to really tout her contributions and role in developing the field. In fact, after the death of her husband, she dedicated much of her life organizing his records and documents, his legacy, at the detriment of her own. However, her work, along with that of her husband, led directly to the spy agencies we have now, such as the CIA and NSA. What they created, however, ultimately led them to become uncomfortable, as the reach of agencies such as the NSA extended far into every aspect of our lives.

An interesting note that relates to our own times. In discussing the context of Germany in the lead-up to World War II, Fagone notes that “The international press covered him [Hitler] like a normal leader. Many Germans did not think he would really do the things he had said he would do.” Perhaps a caution for our own times.

Fagone weaves an excellent story, filling these larger-than-life characters with personality and telling an exciting story involving spies, drug dealers, and the future of Western Civilization. Learning about hidden heroes such as Elizebeth Smith Friedman is always a pleasure, even more so when the story is well executed.