This book is thought-provoking.

This book is thought-provoking.

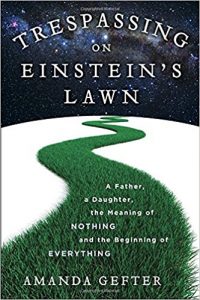

When she was fifteen, Amanda Gefter’s father, while out to dinner at their favorite Chinese restaurant, asked her “How would you define nothing?” Her father had been thinking about the nature of reality and he had come to the conclusion that it was nothing. Or better said, Nothing. This question led Amanda on a journey, both of personal development and to understand the true nature of reality. She delved deep into what physics said about reality. Along the way, in her mind masquerading as a journalist, she interviewed and discussed physics with leading physicists. She delved deep into what the cutting edge of science said about the nature of reality. And, along the way, she discovered her own voice, writing a book detailing her journey.

Gefter’s knowledge and insight about the nature of reality, and the excitement she conveys as she learns it, is simply inspiring. As she tries to uncover what physics says objective reality truly is, she slowly finds, step by step, that nothing is objective. Beginning with relativity that said that time and gravity are relative, and through quantum mechanics, that tells us that even measurements are relative, she examines what we know, what the gaps in our knowledge are, and what that uncompromisingly leads us to conclude about reality. There is no objective reality. Every observer essentially has their own reality, their own definition of the universe.

She jumps into how that means a universe could arise out of literally nothing. As no observer can know everything about the universe, as our views are limited and finite, it puts bounds on the information we can each collect. That bound essentially leads to the formation of the universe, a shadow that arises out of nothingness. I don’t completely understand it, and not sure I buy it all, but the steps by which she gets there are all based on what our science tells us.

In any case, her examination of the science itself is fascinating. I was unaware of what the most recent developments in cosmology, string theory, and quantum mechanics were concluding. Her excitement in discovery each new twist and turn is infectious. And, along the way, she gives great perspectives of the leading thinkers in this area.

This book is humbling.

Gefter has no formal science training. Her father, though a medical doctor, is not a physicist. But, these two delve so deep into questions regarding the nature of reality, it is simply humbling for someone like me who has studied physics. Granted, I went in a different direction, focusing on the properties of atoms and materials, but still, that these two have the curiosity, the drive, and the deep intuition to really delve into these questions is inspiring. I’m inspired to try to delve deeper into my own fields, beyond the every day drivers of doing practical science. We’ll see if I’m able to follow through.

The ideas that Gefter explores, that she describes, are hard concepts and I admit that I struggle with many of them. Most of them arise from simply considerations, typically from seeming paradoxes where some assumption leads to contradictions about how reality must be. In each case, those assumptions must be abandoned and soon we are left with very few. The chain of reasoning and evidence that leads to the final picture is well described, but they ideas are challenging. To fully grasp them, I know I will need to read further.

This book is touching.

Gefter is set on her quest by her father’s question and his own ruminations on the nature of reality. She is both accompanied and followed by her father on this quest as she makes it her own. But, the way Gefter and her father conspire as this journey unfolds, the way they discuss their most recent insights, the way they work together to delve into these deepest of questions, is, in some sense, maybe what all parents dream of. Gefter’s father inspires his daughter to undertake the quest of a lifetime. And she takes it beyond what he could have ever done on his own. The deep intellectual relationship between the two, the shared vision, is something that I could only dream of passing along to my own daughter.

This book is awesome.

The way Gefter explores the nature of reality, the way she starts on her quest knowing literally nothing about the physics of cosmology, quantum mechanics, and relativity, and reaches into the deepest understanding we have, is a great way to convey what we know about reality. She systematically crosses off elements of what might comprise reality and delves deeper and deeper into the seeming paradoxes that arise as our science progresses. I certainly learned a great deal, and the ideas presented are thought provoking in a way that is rare in such books. As opposed to other books on cosmology and string theory, this one doesn’t necessarily take a side or advocate for a certain perspective. Instead, Gefter is really trying to understand what we know and what science tells us about reality. And, in doing so, she produces one of the most entertaining and educational forays into modern physics I’ve had the pleasure of reading.

The ideas that arise from modern physics are mind bending. They push the limits of our ability to understand the world around us. They are beyond our wildest imagination. Science is often criticized for its lack of creativity, but modern physics has created a view of the world and reality that could never have simply been imagined, never dreamed up.