Of the founding fathers, the three that probably stand out are George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. Of these, however, John Adams is probably the one we learn the least about, this in spite of the fact that, of all of the founding fathers, “we” probably know the most about him, a result of his prodigious letter writing and the diaries he kept.

Of the founding fathers, the three that probably stand out are George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. Of these, however, John Adams is probably the one we learn the least about, this in spite of the fact that, of all of the founding fathers, “we” probably know the most about him, a result of his prodigious letter writing and the diaries he kept.

It’s a shame, really, as Adams is both a very important and very interesting character. While Washington certainly merits his place as the father of our country, he is also rather dull, comparatively, having not written his private thoughts. Jefferson is a very interesting character in his own right, a man full of contradictions, embodying both the highs and lows of the human essence.

In contrast, it can be said that Adams is the picture of integrity, the one word that maybe defines his career over all others. He was also loyal to an extreme. Compare his behavior as Vice President to Washington with that of Jefferson’s as Vice President to Adams. Even when Adams disagreed with Washington, his loyalty to the administration meant he wouldn’t undermine Washington’s efforts. Jefferson so disagreed with what Adams tried to do, on the other hand, that he actively tried to derail Adams’ administration.

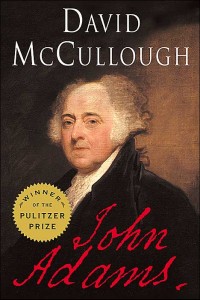

Adams’ long and distinguished service to his country — beginning as a delegate to the Continental Congress, through years as a diplomat in Paris and London trying to secure first the finances to support the Revolutionary War and then to secure the peace, and finally as first Vice President and then President — are admirably covered by David McCullough in his excellent biography of John Adams. McCullough quotes extensively from letters to and from Adams, as well as letters written by his wife Abigail, Adams’ diaries, and newspapers of the time to really bring both the era and Adams to life. In fact, there were times where he spent relatively lengthy sections on, for instance, Abigail’s opinions of French or London society, which felt at times tedious. However, by the end of the book, when Adams’ family members start to pass away, these moments actually hit the reader as, by that time, you are so emotionally invested in these people. The tediousness of those sections is more than made up for by the impact on the reader near the end.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the narrative is the relationship between Adams and Jefferson, which has been of much discussion. Here it comes alive, from the respect they shared at the Continental Congress to their blossoming friendship in Europe to the disintegration of that friendship during their years in the Federal government, only to finally be renewed in their later years. That such a strong bond of friendship could be nearly destroyed by politics is dismaying to watch, especially considering the role that Jefferson — a boyhood idol of mine — played. That these two men could at least partially reconcile their differences should speak volumes to us today.

Another very interesting aspect of the era, related to the relationship between Adams and Jefferson and the politics of the time, is how nasty those politics were. We are often dismayed at how politics is practiced in our day and age. In terms of pure nastiness, however, it does not compare to the politics of the founding of our country. That a great man like Jefferson could attack his one-time friend Adams so strongly and do so hiding behind others is borderline shocking. And Jefferson’s behavior pales in comparison to men like Alexander Hamilton who actively subverted Adams’ own cabinet. Maybe there is a lesson here, that, in spite of how bad things seem to be now, our country has survived worse times and will do so again.

Adams’ life is a fascinating subject and McCullough does a wonderful job of bringing it, well, to life. After reading McCullough’s account of Adams’ life and career, I have a new-found and deep respect for Adams, both as a man and a politician. I highly recommend this book.