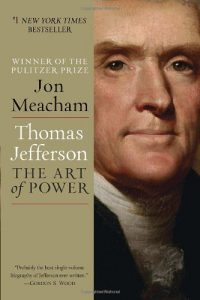

Growing up, my hero was Thomas Jefferson. Here was a man who seemingly did it all: he was of course a leading figure in the founding of our nation, but he was also a gifted writer and a deep thinker, embracing a scientific view of the world. He founded the University of Virginia and, as president, drastically expanded the lands that would eventually become part of the United States. He seemed the epitome of a so-called Renaissance man.

Growing up, my hero was Thomas Jefferson. Here was a man who seemingly did it all: he was of course a leading figure in the founding of our nation, but he was also a gifted writer and a deep thinker, embracing a scientific view of the world. He founded the University of Virginia and, as president, drastically expanded the lands that would eventually become part of the United States. He seemed the epitome of a so-called Renaissance man.

However, as with most things, as I got older, I learned that Jefferson was a much more complex figure, full of contradictions. In the Declaration of Independence, he penned “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” yet, he owned slaves. In fact, he had an ongoing relationship with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings, with whom he fathered several children. He presented a face of aloofness to politics, seemingly above the pettiness of parties, but, behind the scenes, he was actively engaged in attacking rivals and disparaging other ideas. He was against centralized Federal power until he held it and solidified it significantly. He was terribly afraid of what others thought about him but he continued to search out the central position of national affairs.

The point of Jon Meacham’s The Art of Power is to delve into the mind of Jefferson, to explore the seeming contradictions, to understand the full person. Meacham’s goal isn’t to describe in detail all of Jefferson’s accomplishments. In fact, major events such as the revolution, Jefferson’s time in France, even his presidency are, effectively, only briefly described. Rather, it is Jefferson’s innermost thoughts that Meacham tries to probe, mostly through Jefferson’s copious correspondence and the thoughts of his contemporaries. A complex picture arises of a man who, at his core, has two primary drives: he wants to be a great man and he wants the American experiment to succeed. He needed power and control. He needed to shape his life and society to his vision of them.

It is perhaps this that best explains Jefferson’s political life. He was so afraid that Americans, particularly the Federalists such as Adams, would revert to a monarchy of some form — worse, rejoin Britain — that he made it a key mission in his life to subvert such efforts. He felt that an educated people would make the right decision, that education begat reason and that, in turn, would lead to a good government. He expounded “the freedom to use reason publicly in all matters” and that “reason, not revelation or unquestioned tradition or superstition, deserved pride of place in human affairs.” However, he knew that an uneducated public was a danger: “if the members are to know nothing but what is important enough to be put into a public message… it becomes a government of chance and not design.” To make informed decisions, people must be informed. “In a republican nation whose citizens are to be led by reason and persuasion and not by force, the art of reasoning becomes of first importance.”

The contradictions in Jefferson’s life are best embodied in his views on slavery. It seems that he did make some admittedly small efforts to end slavery, or at least mitigate it, but, after a few defeats, he gave up. He didn’t advocate for outright freedom, but emancipation and deportation. He didn’t believe that the two races could live side by side. He realized that the institution of slavery would lead to a crisis, but he, along with many of his contemporaries, decided to punt on the issue of slavery in favor of establishing an imperfect United States. The country would later suffer greatly for this, but, in his mind, there would have been no country if they hadn’t gone this route. Perhaps Jefferson’s biggest failing is that, while he tried so hard to exert his views and meld society to his vision in other aspects, he simply “chose to consider himself powerless” over the issue of slavery. Even in his personal life, he didn’t act on his principles, only freeing those slaves which were his own children (by an arrangement with Sally when she lived with him in France to guarantee her return with him). This is where Jefferson, as a hero, comes crashing down the hardest. This isn’t simply a case where Jefferson was no less enlightened than his peers. There were many who advocated for the end of slavery. Some of his fellow Virginians freed their slaves. Emancipation was not a foreign concept, something that hadn’t even crossed their minds. As Meacham says “Jefferson was wrong about slavery,” even from a contemporary perspective.

His personal life was often filled with days of scientific inquiry. He had an enlightened view on experimentation, stating that “I have always thought that if in the experiments to introduce… new plants, one species in a hundred is found useful and succeeds, the ninety-nine found otherwise are more than paid for.” Further, he knew that not all discoveries immediately led to an amazing new application. He advocated for science for its own sake: “The fact is that one new idea leads to another, that to a third and so on through a course of time, until someone, with whom no one of these ideas was original, combines all together, and produces what is justly called a new invention.” This is a view that science requires sustained effort and encounters much failure for every success, a view that we would do well to continue to adopt in our own times.

Jefferson spoke a strong game when in the political opposition, arguing against any centralization of power and against a strong centralized government. He was a pure democrat. But, upon gaining power, he didn’t hesitate to use it. As Meacham says “It was easy to speak theoretically and idealistically about politics when one is seeking power. The demands of exercising it once it is won, however, are so complex and fluid that ideological certitude is often among the first casualties of actual governing.” This seems to be an insight we could take to heart today. We are often swayed by idealistic arguments about how the government should work, about how society should work, but we neglect the actual difficulties of governing. We are given platitudes about how things will change, but then are frustrated when they don’t change enough. This is how it has been since the founding of the country and is not likely to change any time soon.

Most intriguingly, Jefferson seemed to have a good perspective on his place in history. He was certainly very proud of his achievements, but he also knew that history would inflate them, would place the achievements of his generation on a pedestal to be almost worshipped. “They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human, and supposed what they did to be beyond amendment… I am certainly not an advocate for frequent and untried changes in laws and constitutions… but I know also that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind… We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.” Jefferson knew that people and societies change and that their laws must change with them.

This book isn’t exactly an overview of Jefferson’s life. Rather, it tries to delve into his motivations, his thoughts, using his own words. It tries to understand what drives him. At times, it is a little frustrating in that the context isn’t fully fleshed out — the historical backdrop isn’t always clearly presented, but rather assumed — though to fully paint the picture would have led to an enormous volume. Further, there is no deeper analysis of what Jefferson was thinking. In some sense, he is simply presented, with all of his contradictions. That we can’t delve deeper is frustrating, but the simple fact of the matter is that this is the best we can do. We don’t have him here to talk to, so we can only analyze what he wrote and what others wrote about him. Thus, we are left with an imperfect portrait of an imperfect man, one who stood above others in many ways, but who certainly had his own failings. As Meacham says, “He was not all he could be. But no politician — no human being — ever is.”

I certainly gained a new appreciation for Jefferson, both his accomplishments and the motivations behind them. As an adult, I know no human is perfect and no one can be held up on an unquestioned pedestal. Jefferson, as part of the generation that led to the American experiment, is a great man, a man that is inspiring both for the depth of his thoughts and the breadth of his activities. He is also a small man, for his failures. He is a real human who made enormous sacrifices in some domains of his life but was unable to make others that were equally important. Is he my hero? No. But he is still a man I can admire, understanding that he was, as we all are, a flawed human being.

A few other Jeffersonian snippets I thought worth sharing:

- We have no rose without its thorn; no pleasure without alloy. It is the law of our existence; and we must acquiesce.

- Question with boldness even the existence of a God; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.

- Experience declares that man is the only animal which devours his own kind.

- [Good humor] is the practice of sacrificing to those whom we meet in society all the little conveniences and preferences which will gratify them, and deprive us of nothing worth a moment’s consideration; it is the giving a pleasing and flattering turn to our expressions which will conciliate others and make them pleased with us as well as themselves. How cheap a price for the good will of another!