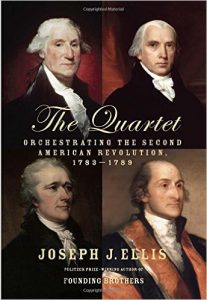

The United States has just fought a long and grueling war for independence. Or had it? What was the goal of that war? Joseph Ellis, noted historian, argues that a collective nationhood, a nation of United States, was not a goal of the war and rather had to be constructed by a group of visionaries, particularly the four men highlighted in his book The Quartet.

The United States has just fought a long and grueling war for independence. Or had it? What was the goal of that war? Joseph Ellis, noted historian, argues that a collective nationhood, a nation of United States, was not a goal of the war and rather had to be constructed by a group of visionaries, particularly the four men highlighted in his book The Quartet.

Ellis argues that the idea and implementation of a nation of the 13 colonies, more than a loose confederation of sovereign states, constituted a second American Revolution, one that embodied the promise of the actual war itself but one that was, in many senses, at odds with the spirit of the war. The war had the stated goal of throwing off a centralized government that did not represent the people at the local level. The establishment of a federal US government was at odds with this view. Further, the very idea of an American nation was something that the vast majority of Americans had never even considered. They were Virginians, New Yorkers, or Georgians, but never Americans.

However, the loose confederation of states embodied by the Articles of Confederation was simply powerless to do anything that required representing the states in any collective way, including collecting funds to pay down the war debt, put forth a consistent foreign policy, or settle disputes between the states. Four men, in particular, saw this problem and led an effort to empower a federal government that could realize the promise of the American Revolution: George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay.

The whole process of the calling of the convention that would lead to the US Constitution was, in some sense, anti-democratic. These were the political leaders of the time, but they operated in secrecy. Further, the ratification of the Constitution was done by state conventions, which were attended by select representatives. If a modern referendum had been called, the Constitution and the very idea of an American nation would have been rejected by the people. However, the representatives at these conventions were not so beholden to popular opinion.

This whole idea is a central and very intriguing aspect of the process. Madison, in particular, was not a fan of direct democracy. He felt that the will of the masses could be easily manipulated by demagogues and were a central threat to the rights of the minority. He preferred what a republic, in which the foundations of power resided with the people, but in which that power was filtered through layers of representatives that, ultimately, did not have to directly respond to the whims of the people. The US was never established to be a direct democracy, but very consciously avoided such a model. Essentially, he “endorsed political structures that filtered popular opinion through several layers of institutionalized deliberation before it became the law of the land.” “He harbored an eighteenth-century sense that unbridled democracy was incompatible with the political health of a republic.” “There was in Madison’s critical assessment of the state governments a discernible antidemocratic ethos rooted in the conviction that political popularity generated a toxic chemistry of appeasement and demagoguery that privileged popular whim and short-term interests at the expense of the long-term public interest.” Ellis examines this view in great depth. It is an interesting and, to our modern sensibilities, jarring perspective. He summarizes this juxtaposition thusly: the Constitution “manages to combine the two time-bound truths of its own time: namely, that any legitimate government must rest on a popular foundation, and that popular majorities cannot be trusted to act responsibly, a paradox that has aged remarkably well.”

There were of course many contradictions in the establishment of the United States, as a nation, and the ideals of the American Revolution. One of the central tenets of the war was that “all men are created equal.” However, the US certainly didn’t view the Native Americans or slaves as equals. The domestic policy of the US was that civilization would naturally and simply march westward, displacing the Native Americans, without any direct claim of imperialism. Further, the slave issue could not be resolved in the convention, as to directly address the issue would lead to a still-birth of the nation. “…slavery was, on the one hand, a cancerous tumor in the American body politic and, on the other, a malignancy so deeply embedded that it could not be removed without killing the patient.” “Moral purity on this score would come at the cost of American nationhood.” This is how the men at the Constitutional Convention justified simply skirting the issue. However, one does wonder how history might have developed if they had taken the moral high road and pushed to abolish slavery at that time.

Once the Constitution was written, it had to be ratified, and that entailed a whole new battle in the hearts and minds of the citizens of the future United States. Ellis describes the efforts of primarily Hamilton and Madison, along with Jay, to convince the various state delegations to ratify the Constitution. They played a very political game, trying to get enough states to ratify before the heavy hitters — Virginia and New York — held their conventions to ensure enough political pressure on them to ratify. In the end, ratification was not as certain as one would expect from our historical perspective. Ratification did not represent the will of the people, but rather “superior organization, more talented leadership, and a political process that had been designed from the start to define the options narrowly.” The Bill of Rights, first drafted solely by Madison, had a similar political goal of ensuring that the Constitution would not be challenged by any of the states in the newly formed United States.

One key ingredient of this new Constitution was its vagueness. Issues such as sovereignity between the federal and state levels and slavery led to what Madison called a “living” document, one that “was intended less to resolve arguments than to make argument itself the solution.”

We often view the founding of the United States in almost semi-mystical terms, almost deifying the founders themselves as super-human agents of change. However, the truth is far from this picture and the very founding of the United States was never a forgone conclusion. Ellis’ analysis of this uncertain time provides new insight into the birth of our nation. His use of Washington, Madison, Hamilton and Jay as the vehicles of this change provide a human perspective, shedding light into the doubts these men had in their endeavor and the possibility of success.

I highly recommend this book for the historical perspective it gives into the development of the United States as a nation.

Like this:

Like Loading...