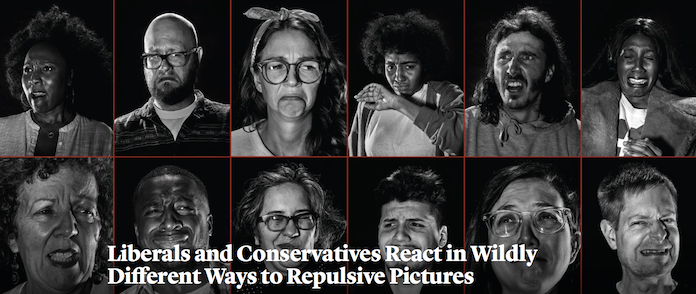

In the March 2019 issue, The Atlantic published a very interesting story about the differing reactions between liberals and conservatives to “disgusting” images. Summarizing a study by Read Montague, a neuroscientist at Virginia Tech, and his colleagues, the story reports that liberals and conservatives have measurably different responses to images such as “mutilated animals, filthy toilets, and faces covered with sores.” They found that, monitoring people’s reactions via MRIs, he could predict whether they were liberal or conservative with 95% accuracy. They further found that “conservatives tend to have more pronounced bodily responses than liberals when shown stomach-churning imagery.”

This is pretty amazing, if you ask me. It suggests that, to a large extent, our political views are not shaped by reasoned thought about the issues. Rather, they are strongly determined by neurological processes that we simply don’t control. “Gut reactions” to repulsive things. Regardless of which side of the proverbial aisle one sits on, if our beliefs are so strongly connected to primal reactions, what does that mean for democracy?

Democracy relies upon reasoned debate, with the goal of reaching compromise on complex issues. No one is ever fully satisfied, but to convince the other side to go along with your point of view, you have to persuade them that you have a solid argument. Debate is all about convincing the other side of your point of view. But, if your point of view is essentially a function of your gut, what is there really to convince them of? What is there to argue about? You can create arguments to support your belief, but that is building the scaffolding after you already have the core. Rather, informed debate should be about defending beliefs that you have based on reason. We shouldn’t be defending beliefs post-facto, but develop our beliefs based on the evidence around us. If our beliefs are founded on gut reactions, we are always going the wrong way.

To me, this has profound implications for democracy. We hope, that when our politicians are working, debating, arguing, fighting for something they believe in, even if they don’t agree with you or me, that at least they have strong reasons for their beliefs and that they are working to better society based on those beliefs. But, if they really don’t have any foundation for their views beyond their gut reaction, their neurological impulses, how solid can those beliefs and the subsequent arguments be? How well can they be tied to our best interests? If they are not based on evidence or reason, can they truly be the foundation of policy?