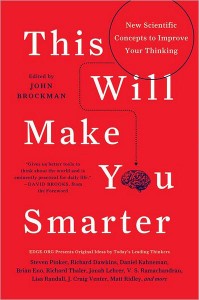

Each year, John Brockman and Edge.org ask a group of renowned scientists and thinkers a thought provoking question to stimulate discussion about important topics. In 2011, he asked “What scientific concept will improve everybody’s cognitive toolkit?” Something like 150 people contributed short essays with their answer to the question. They range from profound to rather silly (at least, in my opinion). But they all provide new ways of thinking about the world around us.

Each year, John Brockman and Edge.org ask a group of renowned scientists and thinkers a thought provoking question to stimulate discussion about important topics. In 2011, he asked “What scientific concept will improve everybody’s cognitive toolkit?” Something like 150 people contributed short essays with their answer to the question. They range from profound to rather silly (at least, in my opinion). But they all provide new ways of thinking about the world around us.

For example, P. Z. Meyrs discusses the “mediocrity principle”. Simply put, it means that you, or me, or any of us, aren’t special. We aren’t the center of the universe. Things don’t happen to us for a reason. The universe isn’t out there to either help us or hurt us. It just is, and we are just a part of it. Sean Carroll follows up on this, by stating “Humans… like to insist that there are reasons why things happen… [that things] must be explained in terms of the workings of a hidden plan” but, in the end, there is no such plan. In a twist to this idea, Samuel Barondes points out that, while each of us is ordinary, we are also each one of a kind.

Jonah Lehrer discusses research on willpower with an example of 4-year-old kids. These kids were sat down in a tiny room and presented with treats. They could either eat one now, or if they could way for a few minutes alone in the room, they could have two treats when the time was up. Some kids waited and some did not. In the end, it wasn’t a matter of kids having more or less willpower, but the kids who could wait for the two treats were better able to distract themselves, focusing on something else rather than the treats. The most important result: the kids who could wait, who could distract themselves from the most immediate reward, scored 210 points (on average) on SAT tests in high school compared to those who didn’t last 30 seconds before grabbing a treat. As Lehrer states, “these correlations demonstrate the importance of learning to strategically allocate our attention.” If we can learn to focus on things other than the immediate reward, we can improve our overall lot in life.

Another theme that is explored by multiple authors is the human brain’s inability to really assess risk. We inordinately fear things that have an extremely low probability of happening while we don’t give a second thought to things that actually are relatively likely. Garrett Lisi summarizes this paradox nicely: “The startling implication is that the risk of being bitten and killed by a spider is less than the risk that being afraid of spiders will kill you because of the increased stress.” That is, the stress of being afraid of spiders is more deadly than the spiders themselves.

One last example is by Jason Zweig. I like it because, in an ideal world, I would try to implement this in my own life. He focuses on serendipity, and how to nurture the creative process that lead to those Eureka! moments. In particular, he says that research shows that serendipity is a consequence of abrupt shifts in the focus of our brain activity. It is when the brain completely shifts gears. To facilitate this, he personally tries to read one scientific paper each week that is not in his field and to read it in a completely different place. The idea is to break his routine, to force his brain into new circumstances, with the goal of promoting shifts in the focus of the brain. I like the idea; I just need to find some time to do it.

There are a lot of other essays that are very interesting, going into various aspects of the scientific method, or principles from economics, or the role of randomness in our lives. Like the other books in this series, I highly recommend it, if for no other reason than to provide food for thought about how both our brains and the universe they find themselves in work.