|

Hasiera · Home |

|

Ezaugarriak · Features |

|

Oharrak · Notes |

|

Sarrera · Introduction |

|

Euskara |

|

Folklore |

|

Kirolak · Sports |

|

Musika · Music |

|

Janedanak · Gastronomy |

|

Tokiak · Places |

|

Historia · History |

|

Politika · Politics |

|

Diaspora |

|

Internet |

|

Albisteak · News |

|

Nahas Mahas · Misc |

For security reasons, user contributed notes have been disabled.

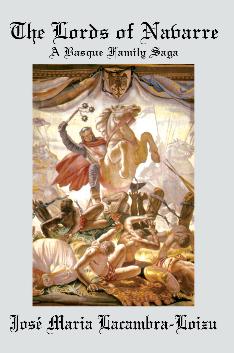

by Jose Mari Lacambra

Fiction / Historical

Trade Paperback

Publication Date: May-2004

Price: $23.95

Size: 6 x 9

Author: José Maria Lacambra-Loizu

ISBN: 0-595-31148-2

428 Pages

On Demand Printing

Available from Ingram Book Group, Baker & Taylor,

and from iUniverse, Inc

To order call 1-877-823-9235

Drawing from family lore and heraldic

records, The Lords of Navarre

traces a Basque family's history from the last Ice Age to the present.

Meticulously researched and authoritatively written, this absorbing

narrative recounts the untold story of a people who left us their handsome

cave paintings and continue to speak the haunting voices of their

Cro-Magnon ancestors.

This epic saga chronicles the lives of

successive generations of Basque warlords who migrated from the Caucasus

forty thousand years ago, tangled with Neanderthals and settled in Pyrenean

highlands which they fiercely defended against Celts, Romans, Franks, Moors

and Castilians. In sharp, time-sequenced snapshots, their destinies and

fortunes intertwine with those of Julius Caesar, Abd-el-Rahman,

Charlemagne, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Richard the Lionheart, the Black Prince,

Sancho el Fuerte of Navarre, Cesare Borgia, and Ferdinand and Isabella of

Castile.

A central theme in this narrative is

their involvement in the Reconquista, an eight century-long struggle to rid their land of occupying

North African Moors during the Dark and early Middle Ages, an ancient

struggle that eerily presaged today's renewed conflict between East and

West. With the nagging persistence of an unscratched itch, this déjà-vu of

that earlier conflict challenges current misguided attempts to suppress

stirring battle cries like “Santiago, Moor slayer!” from Iberian history

books.

Author's Biography

Of ancient Navarran lineage,

Lacambra-Loizu grew up in the Basque country, studied Humanities at the

Sorbonne, obtained his B.A. and a fascination with history from Gettysburg

College, and earned a Ph.D. in Physics from Duke University. A scientist by

profession and a humanist by avocation, he trains an inquisitive eye on the

spellbinding history of his own Basque family. Now happily retired, he

lives with his wife, Ann, in Winter Park, Florida.

|

Recent breakthroughs in linguistic and genetic investigations, however, confirm the even more startling thesis that the Basques are stragglers of the first group of Cro-Magnon to venture out of the Middle East during the middle Paleolithic to displace the Neanderthals and settle Europe. Keys to the survival of this racial isolate were the abrupt mountain valleys and near-impenetrable Pyrenean forests they chose to inhabit. The reluctance to share their gene pool with subsequent invaders helped preserve their ancestral traits and archaic morphology. So formidable were these geographical and cultural barriers, so effective their genetic isolation that the Basques managed to retain some of the vestigial traits that classify them as one of the handful of relic races remaining on earth today.

Linguists and anthropologists have long tried to solve the riddle of their origins. The mystery remained largely unsolved until recently, when a Spanish linguist [1] succeeded in breaking the Iberian hieroglyphic cipher, conclusively proving that the inscriptions engraved on Iberian vases, tombstones and lead tablets unearthed in eastern Spain represent Basque words written in archaic Phoenician or proto-Greek alphabets. This confirmation of an old conjecture underscores the intriguing hypothesis that the Basques - read "Iberians" - come from the Caucasus. Over two thousand years ago Egyptian [2], Greek [3] and Roman [4] sources identified the inhabitants of the southeastern foothills of the Caucasus as "Iberians." Strabo's and Pliny's commentaries further aver that, during Roman times, Iberian was widely spoken in Aquitaine, a vast region in southwestern France.

Combined with the ice-aged words fossilized in their language, this wealth of clues strongly supports the thesis of an Iberian ice-age migration from the Caucasus to Western Europe and their eventually crossing the Pyrenees to settle in the peninsula that bears their name today. Corroborating this conjecture is the recent genetic sleuthing [5] of Basque mitochondrial DNA, confirming that just such a migration took place some forty thousand years ago, right about the time of the first Cro-Magnon incursion into Europe.

While the vast majority of peninsular Iberians and their trans-Pyrenean kin in Aquitaine eventually lost their original ethnicity on melding with subsequent invading cultures, quite another fate befell those who remained in fairly inaccessible pockets of the western Pyrenean mountain valleys. Inspired by a fierce spirit of independence, these few, endogamous stragglers managed to retain their archaic language, their relic racial characteristics and their original blood genotype. It is startling to realize that the Neolithic artists of those handsome cave paintings of Lascaux, Niaux, Isturitz and Altamira were Basque. It is equally intriguing to conjecture that listening to spoken Basque today may be like listening to a scratchy millennial tape recording of our Cro-Magnon ancestors.

During a recent visit to my ancestral home in the Spanish Pyrenees, I happened across a sixteenth century manuscript claiming family roots that dated back to "time immemorial." This startling discovery encouraged me to anchor this chronicle in the prehistoric past, describing a journey spanning the last glacial age to the present. It narrates the meandering of a family of Vascon warlords, the Agorretas, as they grope their way out of the prehistoric mists and into the glare of history.

The account begins during the brief warming spell of the Pandorf Interstadial, some forty-thousand years ago. A band of nomadic hunters abandons its Caucasian caves to pursue the big game, which has retreated to the northern tundra following the receding ice cap. As the weather turns cold again, during the peak of the Würm glaciation some twenty thousand years later, the big game and its pursuers retreat south, keeping one step ahead of the advancing ice sheet. The hunters seek shelter in caves at the foot of both the Massif Central and the Pyrenees and leave their artistic imprint in cave paintings along the way.

As this band of Vascon hunters finally surfaces into history, we see them rub reluctant elbows with Celts, join the Roman legions in the Rhine, tangle with Charlemagne at Roncevaux, and fight North African Muslims in battles from Covadonga to al-Andalus, always fiercely defending their beloved Vascon valleys in the Pyrenean uplands. Later, and now at the cusp of the age of chivalry, an Agorreta participates in jousts, takes the Cross in the Lionheart's Crusade, and woos a Moorish princess whose brother he later helps defeat in the turning-point battle of Navas de Tolosa. Later still, now in the thick of the Middle Ages, another Agorreta crosses swords with the Black Prince at Crecy and later fights under the Englishman's banner at Nájera. Finally, during the twilight years of the Vascon kingdom of Navarre, several Agorretas attain Royal Judgeships, serve as Seneschals to kings and bear brave lances under Cesare Borgia. The chronicle ends on the eve of the annexation of a once fiercely independent Vasconia to the nascent kingdom of Spain.

Although generous literary license is taken when narrating prehistoric events, actual family names and events are cited whenever historical records exist. Thus, although the early Agorretas described in this chronicle are fictional, the later characters did, in fact, leave their imprint in Navarran history as borne out in Navarre's heraldic records.

One last comment should help clarify the otherwise confusing interchangeable usage of the terms Basque, Vascon and Gascon in this chronicle. Although the term Basque is inclusive and embraces the other two, the "Vascon" designation is the most ancient, having been first employed by the Greek cartographer Strabo to identify the inhabitants of the southwestern corner of the Pyrenees. The "Vascon" appellation merely distinguishes those Basques inhabiting the southern slopes of the Pyrenees from those living in the northern slopes who are called "Gascons." Another, now archaic geographical designation frequently employed in this narrative is Aquitaine, a vast region in southwestern France extending from the Loire to the Pyrenees, once peopled by Basques. First identified by Julius Caesar as one of Gaul's three parts, this, the "watery one," was a region briefly ruled by the English centuries later during the Hundred Year War.

J.M.L.

Footnotes:

[1] Jorge Alonso Garcia, "Desciframiento de la Lengua Ibérico-Tartésica," Fundacion Tartesos, Spain 1997

[2] Ptolemy Geography Book 5, Ch. 10

[3] Strabo Geography, 11.1.5, Loeb

[4] Pliny Book 3, Ch. 3, 29

[5] Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Genes, Peoples and Languages, North Point Press, 2000.

|

Please report any problems or suggestions to Blas. Eskerrik asko! |