Besteren ama ona, norberea askoz hobea.

Other people’s mothers may be good, but never as good as ours.

These proverbs were collected by Jon Aske. For the full list, along with the origin and interpretation of each proverb, click this link.

Besteren ama ona, norberea askoz hobea.

Other people’s mothers may be good, but never as good as ours.

The Basque Country holds so many hidden gems. We are all familiar with the big places – Donostia, Bilbo, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Pamplona/Iruña – but there is so much more to see. Spectacular waterfalls. Strange geological forms. Nature reserves. Small villages untouched by modernization. Ainhoa falls in this last category. A small town in Lapurdi on the border between France and Spain, it has seen a lot of history. Despite all of the conflict, it has managed to retain a medieval charm.

What are your hidden Basque gems?

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Estornés Zubizarreta, Idoia; Berger, Marie Claude. AINHOA. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2025. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/ainhoa/ar-7408/; Ainhoa, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Wikipedia; Ainhoa, Le Guide de Pays Basque; This medieval Basque village survived destruction in 1629 – its red-and-white houses hide France’s most authentic pilgrimage town, World Day; Aïnhoa a charming medieval village, Biper Gorri Camping

Besteen faltak aurreko aldean, geureak bizkarrean.

Other people show their faults up front. We hide ours behind our backs.

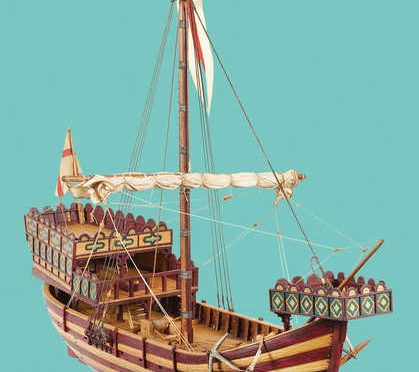

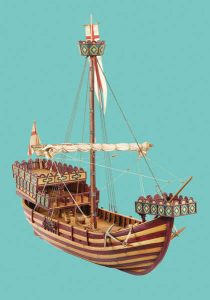

The Basques weren’t the first to explore the seas… or were they? The Basques didn’t invent boats… or did they? The Basques aren’t aliens from outer space… or are they?

Seriously, the Basques played an important part in the development of shipbuilding and seafaring. We know that they were outstanding navigators, but their contributions go beyond that, to also improving ship technology. As a sort of nexus between northern and southern Europe, they fused technologies to make things even better.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Zwick, Daniel: “Bayonese cogs, Genoese carracks, English dromons and Iberian carvels: Tracing technology transfer in medieval Atlantic shipbuilding”, Itsas Memoria. Revista de Estudios Marítimos del País Vasco, 8, Untzi Museoa-Museo Naval, Donostia-San Sebastián, 2016, pp. 647-680; Guided pollards in the Basque Country (Spain) during the Early Modern Ages by Alvaro Aragón Ruano

by Sancho de Beurko Association

From Family Memory to National Recognition

For decades, the story of Basques and Basque Americans who served in the United States Armed Forces during World War II lived quietly within families and local communities — preserved in fading photographs, personal letters, and stories shared at kitchen tables, yet largely absent from the public historical landscape.

Today, that story is finally beginning to take physical form.

The Basque American community has officially announced both the location and the conceptual design of the National Basque World War II Veterans Memorial — the first national memorial in the U.S. dedicated exclusively to honoring WWII veterans of Basque origin.

The Memorial is a project of North American Basque Organizations, Inc. (N.A.B.O.), developed in close collaboration with the long‑term historical research initiative Fighting Basques: Memory of WWII, led by the Basque homeland association Sancho de Beurko. Together, these efforts seek not only to commemorate the past, but to bring into public view a long-overlooked chapter of American and Basque history.

A national fundraising campaign launched in 2024 supports both the continued historical research and the construction of the Memorial, with completion envisioned by the end of 2026.

The Legacy of the “Fighting Basques”

Years of archival research, oral history, and sustained collaboration with families have now made it possible to identify more than 2,150 men and women of Basque origin who served in the U.S. Armed Forces during WWII, including members of the U.S. Merchant Marine.

At the time of their enlistment, these veterans lived in thirty U.S. states, as well as Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico — covering nearly 60% of the United States’ territory. They served in every branch of the U.S. Armed Forces and in every theater of operations worldwide.

The majority were American born: approximately 85% were citizens by birth, mostly the children or grandchildren of Basque immigrants. Yet more than 260 veterans were born in the Basque Country itself, and others came from Basque communities across ten different countries, from Argentina and Mexico to the Philippines and the United Kingdom. Over half of these emigrants were not U.S. citizens when they enlisted.

Their paths to service were diverse, but their commitment was shared. Together, they represent an extraordinary and still underrecognized contribution to the history of World War II.

Gardnerville, Nevada: A Meaningful Home

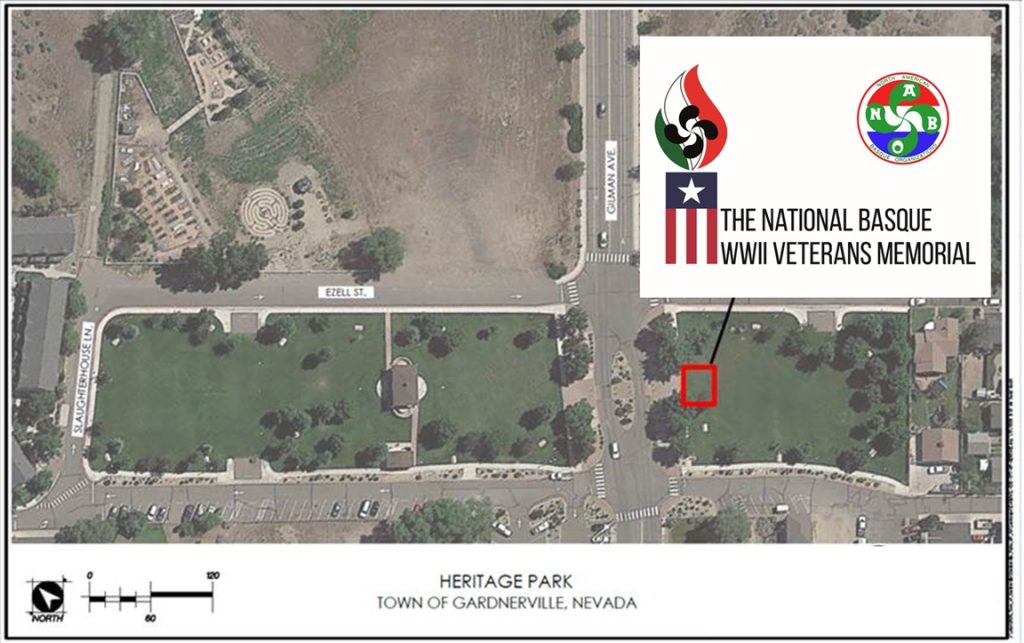

After an intensive year-long process of research, site visits, and deliberation, N.A.B.O. has announced that the Memorial will be built in Gardnerville, Nevada, at Heritage Park, located in the town’s historic downtown.

This location is deeply meaningful. Rooted in a rich immigrant past, Gardnerville has long been — and continues to be — an important center of Basque American life in Nevada. Founded in 1879, the town later became one of the state’s most significant sheep-raising hubs, sustained by a dense network of boardinghouses, hotels, bars, and restaurants that served generations of Basque sheepherders and their families.

Today, Gardnerville remains home to an active and engaged Basque community. With just over 6,200 residents, the town represents nearly 2% of Nevada’s Basque population and hosts the Mendiko Euskaldun Cluba. Since its founding in 1981, the club’s events and annual festivals have been widely attended, drawing participants from across the state and beyond, and serving as a regional reference point for Basque culture.

The Town of Gardnerville has also expressed its support for the Memorial project, recognizing its historical, cultural, and educational value for the community and working collaboratively with the organizers as the initiative moves forward.

Gardnerville is also closely linked to families whose wartime service became legendary—such as the Etchemendy brothers, often described as the most decorated group of brothers in Nevada. Born in Gardnerville to Basque immigrant parents, their names will soon return home, permanently engraved at the Memorial.

Bizi leku: A Place to Live, A Place to Remember

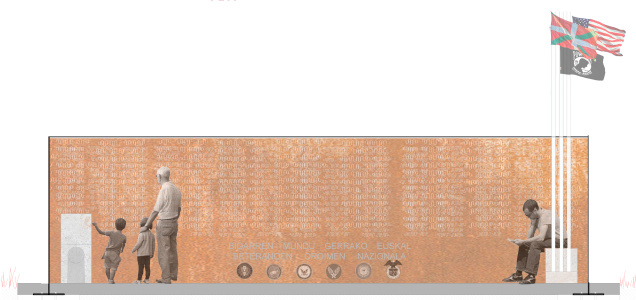

The Memorial’s conceptual design, titled Bizi leku — Basque for “The Place to Live” — was created by Basque architect Maider Bezos Lanz (BZS Architecture).

Constructed in Corten steel, the design evokes themes of migration, settlement, and belonging. It reflects the experience of adopting a new homeland while maintaining deep cultural roots—a defining feature of the Basque American story.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

“Bizi leku is conceived as a welcoming space,” explains Bezos Lanz. “A symbolic home that brings together all the names engraved on its surfaces, allowing them to coexist in peace and dignity — united by shared history and memory.”

The Memorial is envisioned not simply as a list of names, but as a living place of remembrance — one that honors individual lives, family histories, service, and sacrifice. A complementary digital memorial will provide access to biographies and educational resources, extending its reach far beyond the physical site.

Looking Ahead: A Shared Responsibility

The National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial seeks to preserve the memory of an entire generation while offering visitors — Basque and non‑Basque alike — a space for reflection, learning, and gratitude.

“As a community, we are creating a permanent national place to remember, honor, and thank Basque veterans who proudly served during World War II,” says historian Dr. Pedro J. Oiarzabal, director of the Fighting Basques project. “It represents a long-overdue public recognition and a place of pride, service, and belonging — one that connects individual stories to our shared history, much like the National Monument to the Basque Sheepherder dedicated in Reno, Nevada, in 1989.”

The Memorial’s dedication is planned for no later than December 2026, coinciding with two significant anniversaries: the 85th anniversary of the U.S. entry into World War II and the 250th anniversary of American independence.

Yet this Memorial is not only about the past. It is about how memory is carried forward — through care, participation, and collective commitment — so that these stories remain present and meaningful for future generations.

The National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial will take shape through shared remembrance and community involvement. As the fundraising campaign continues, each contribution — large or small — helps transform memory into a lasting public space of recognition and gratitude.

In this way, the Memorial becomes more than a site or a structure. It becomes a place where history remains alive—because a community chooses to remember, together.

Over 100 years ago, in 1921, José Miguel de Barandiaran began publishing a series of articles under the banner of Eusko-Folklore. His work was interrupted by the Spanish Civil War but in 1954 he resumed publishing what he then called his third series of articles. These appeared in the journal Munibre, Natural Sciences Supplement of the Bulletin of the Royal Basque Society of Friends of the Country. While various writings of Barandiaran have been translated to English, I don’t believe these articles have. As I find this topic so fascinating, I have decided to translate them to English (with the help of Google Translate). The original version of this article can be found here.

IN AMEZQUETA

Our mother saw how Mari de Txindoki left. She lived in the mill when she was little. Once, some men brought a pile of sacks of corn to the mill on a cart, and our mother unloaded the sacks from the cart onto the men’s shoulders. And, while the men were returning, as she was waiting for them, at night, she saw something burning and flaming coming out of the Txindoki chasm and disappearing [going] toward San Miguel. Our mother was frightened. Later, when the men had returned, she told them that she had seen something burning and flaming heading toward San Miguel [de Aralar]. They then replied that it was undoubtedly Mari. In the chasm where she [Mari] entered, everything was scorched.

(Reported in 1930 by Ignacio Altuna, from Amézqueta.)

IN BIDARRAY

The story of the apparition of Arpeko-Saindua (the saint of the cave) on Bidarray Mountain is similar to those recorded in previous legends about Mari. The themes of the blast of fire that enters a cave at night, the young woman who mysteriously disappears, the threatening voices of the night, and the curse and punishment of those who desecrated the cave all converge here, as in other stories about Mari.

On November 14, 1938, I visited the cave of Arpeko Saindua, accompanied by my friend Don Gelasio Arámburu and the Jatxou children’s colony.

We arrived at Bidarray station early in the morning. We crossed the Nive over the bridge called Onddoene’ko zubi (Onddoene Bridge). It is said that this bridge was built in one night by the legendary spirits whose name is lamin. We took a path to the right that climbs alongside the Bastan-erreka stream. We pass close to Arranteia (the swimming pool). Further on, we cross the stream in a narrow ravine over the Inpernuko-zubi (Hell’s Bridge), and continue along the path to cross the stream again higher up and take the path that climbs to the Arrusia baserri located on

the southern slope of Mount Zelharburu. Still traveling uphill for 300 meters, heading west-northwest, we reach the Arpeko Saindua cave. Its entrance faces east-southeast. It is open in the banks of pudding stone and sandstone that form the southern escarpments of Mount Zelharburu. It has a vestibule 5 m wide, 5 m deep, and 6 m high. To the left, a meter and a half above the floor of the vestibule, there is a narrow gallery that is accessed by ten stone steps (fig. 1). It is a humid place: water drips from the ceiling. At the end of the gallery (fig. 1, x), there is a stalagmite column that reaches the ceiling: it measures 1.10 m in height and 0.20 m in average width. It resembles a human torso (fig. 2). A little water runs across its surface. This is the supposed saint of the cave. The etxekoandre, or lady of the Arrusia baserri, named Margarita Ibarrola, tells me the following:

A young girl got lost on Mount Euzkei [Iuskai, Iuskadi]. They only found her head. From then on, at night, for many years, voices were heard. “Wait! Wait!” someone shouted from the side of Mount Euzkei.

On one occasion, at midnight, they saw a light enter Zelharburu’s cave. Others said they had seen twelve lights. The surrounding villagers went to the cave and there saw the statue of the saint. From then on, the voices were not heard.

In front of the stalagmite column, there are candlesticks resting on rock outcrops. In them, devotees place the candles they offer to the “saint” and rub their bodies or sick limbs with the water that runs down the supposedly petrified “saint.”

She is invoked in cases of skin and eye diseases. Those who suffer from eczema (negal in Basque) are the ones who have particular devotion to the “saint” of this grotto.

While still inside the cave, we saw three women arrive from the Itxassou side with two girls. One of them, a young girl, lit a wax candle, traced a cross in the air with it in front of the stalagmite, and left it at its foot to be consumed there.

I returned to Zelharburu on April 20, 1945, and saw that the cult of the saint of the cave continued as before.

On the walls of the cave are many votive offerings: rosaries, crosses, medals, combs, handkerchiefs, shirts, and berets that the sick leave, believing that the illness that afflicted them remains in these garments. There is also a collection box where devotees deposit alms (cash and paper money). Since the collection box is broken, anyone can steal the money deposited there: many 10- and 20-franc bills can be seen. In the hollow beyond the stalagmite, we saw several bronze coins from the last century: some French and some Spanish. They were undoubtedly thrown there not to cover the expenses incurred by the care of that “sanctuary,” but for the supposed “saint” venerated there, and only for her. The almost inaccessible nature of the place where they were thrown shows that their donors did not want those coins to fall into human hands.

Both the devout pilgrims of Itxassou and one of the shepherds from the region named Antonio Intxaurgarate told me that, on one occasion, the owners of Arrusia closed the cave and began charging an entrance fee to those who came to visit the “saint.” Soon, all of the sheep of Arrusia fell into disgrace, tumbling down the rocks. The family of Arrusia then realized that this was a punishment sent by Arpeko Saindua and reopened the cave.

A pilgrimage is held here annually on Trinity Day, consisting mainly of dancing. Groups of young people of both sexes from the surrounding neighborhoods and villages attend.

There are procedures to attract Mari, and there are also those to remove her.

If she is invoked three times in a row, saying: Aketegiko Damea! “The Lady of Aketegi!”, Mari then appears and she sits herself on the head of the person who invoked her. This is the information we gathered from a report from Cegama.

But there are also means, mainly of a religious and magical nature, to which the power of preventing any action by Mari is attributed.

We have already recorded some cases of this kind on various occasions. Now I will simply transcribe the brief report that a resident of Mañaria sent me in 1930. It reads somewhat literary:

One afternoon, three or four of us were going for a walk, spending time in the mountains, taking time in the shade of a tree, and were talking and resting beside a stream. Suddenly, an old shepherd appeared and also rested beside us.

We talked with the old man for a long time and talked about many things, and finally, we recalled the storms that had raged here and there during this summer, etc. We talked about the weather in so many ways, each of us offering his own opinion. At this point, the old shepherd stood up and, thoughtfully, looked at us to tell us something important about the weather. Then he began to explain very seriously the cause of the storms. “Look! If the Lady of Amboto is inside the cave on Saint Barbara’s day, the following summer will be calm and abundant [in crops, etc.]; but if on that day she is outside the cave, the following summer there will be terrible storms and upheavals. And on Saint Barbara’s day last year, that Lady of Amboto walked in fire and flames along the Mugarra (1) side, and that is why all the storms, tempests, and evils this year are here.”

(1) Mugarra is a mountain located above Mañaria.

SUMMARY OF THE MYTHOLOGY OF MARI

Taking a look at what we have published so far about Mari, both in EUSKO-FOLKLORE and in “Mari o el genio de las montañas” (in Homage to D. Carmelo de Echegaray, San Sebastián, 1923), in “Die prähistorischen Höhlen in der baskischen Mythologie” (in Paideuma, Leipzig, 1941), and in “Contribución al estudio de la mitología vasca” (in Homage to Fritz Krüger, Mendoza, 1952), we could briefly summarize the main features of the conceptual and mythological world formed around this legendary name or divinity.

Names

Mari is the most general, alone or associated with the place where the numen resides:

The name Mari may have some connection with the names Mairi, Maide, and Maindi used to designate other legendary figures in Basque mythology, although the themes associated with these are different. The Mairi are the builders of dolmens; the Maide are male spirits of the mountains, while their female counterparts are the Lamin, or spirits of springs and rivers; the Maindi are perhaps the souls of ancestors who visit their former homes at night, according to beliefs in the Mendive region.

The name Maya undoubtedly has a connection with Maju, who is considered to be Mari’s husband and must be the same name that Lope Garcia de Salazar called Culebro, father of Jaun Zuria, and in Ataun they call Sugaar “snake” and in Dima Sugoi “snake.”

Forms of Mari

Legends attribute Mari to the female sex, as they do to most of the deities featured in Basque mythology.

Mari often appears in the form of an elegantly dressed lady, as we are told in the legends of Durango, in which she also appears holding a golden palace in her hands. She is similarly represented in the stories of Elosua, Bedoña, Azpeitia, Cegama, Rentería, Ascain, and Lescun. In the latter town, she wears a red skirt.

Despite the variety of forms in which legends present Mari, they all agree that she is a woman.

Mari generally takes on zoomorphic forms in her underground dwelling; other forms outside of it, on the surface of the earth, and when she crosses the firmament.

The animal figures such as bulls, rams, goats, horses, serpents, vultures, etc., that are mentioned in the legends concerning the underworld, therefore represent Mari and her subordinates, that is, the terrestrial spirits or telluric forces to whom people attribute the phenomena of the world. The cases of changes in form, mentioned in various stories, confirm this idea.

Mari’s Abodes

Mari’s ordinary abode is the regions beneath the earth. But these regions communicate with the earth’s surface through various channels, which are certain caverns and chasms. For this reason, Mari appears in such places more frequently than in others.

(To be continued)

José Miguel de Barandiaran

Beste lekutan ere, zakurrak oinutsik ibiltzen dira.

In other places, dogs go barefoot too.

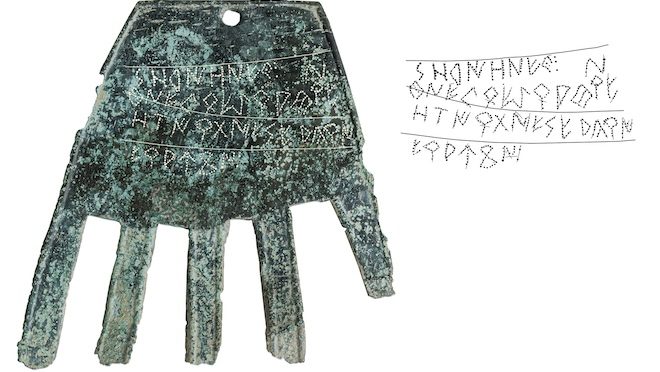

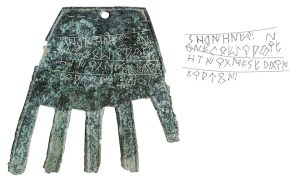

The origins of the Basque language are lost to time, or so we are told. However, new discoveries such as the Hand of Irulegi challenge some of those assumptions and reveal new and exciting insight. At the same time, researchers continue to chip away, examining the body of evidence to further our understanding of the origins of the language and its possible connection to other languages. As a consequence, old theories such as the relationship between Basque and Iberian are getting a new look.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Estornés Zubizarreta, Idoia. VASCO-IBERISMO. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/vasco-iberismo/ar-130027/; New Connections Discovered Between the Ancient Iberian Language and Basque, Beyond Numbers by Guillermo Carvajal, La Brújula Verde; One of Europe’s Most Mysterious Languages May Share Ancient Roots with Iberian by Oguz Kayra, Arkeonews

Berri gaiztoa bera zaldi.

Bad news is like a horse.

by Sancho de Beurko Association

On Friday, February 13, and Saturday, February 14, the Basque American community and guests will gather at the Basque Cultural Center of South San Francisco for a deeply meaningful occasion: the official announcement of the city and architectural design of the National Basque World War II Veterans Memorial.

These events take place within a very special context—the celebration of the 44th anniversary of the Basque Cultural Center, an institution that for more than four decades has served as a cornerstone of Basque cultural life, memory, and community in the United States. Framing the Memorial announcement within this anniversary highlights the continuity between past, present, and future that defines this moment.

A weekend of remembrance, gratitude, and shared purpose

The weekend will include two complementary events.

On Friday, February 13, a private donor appreciation dinner will recognize those who have helped bring the Memorial project to this important stage. The dinner is hosted by the North American Basque Organizations, Inc. (N.A.B.O.), the group leading the effort to build the Memorial.

On Saturday, February 14, a public presentation will take place at 2:00 p.m. The presentation will be delivered by Dr. Pedro J. Oiarzabal, historian and research project director, who will publicly unveil both the host city and the design concept of the National Basque World War II Veterans Memorial, marking a major milestone in the project’s development. This talk is free and open to everyone. Seating is limited, so early arrival is encouraged.

For the first time, the National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial moves from vision to place—anchored in a specific landscape and shaped by a design conceived as a permanent space of remembrance, education, and public history.

Honoring lives, stories, and living memory

The Memorial honors more than 2,150 WWII veterans of Basque descent who served in the United States Armed Forces, including the Merchant Marines—most were children of immigrants, whose service has often remained absent from broader national narratives.

This history is not distant or abstract. It is still embodied today in living memory. Among those we honor are two centenarian women veterans, Basque Californian Anna Biscay and Basque Idahoan Regina Bastida, both 104 years old, whose remarkable lives and service remind us that this project is ultimately about people—about courage, resilience, and devotion to duty. Their stories, like so many others, give a human face to the history the Memorial seeks to preserve, and continue to inspire new generations.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

A milestone for collective memory

Since the inauguration of the National Monument to the Basque Sheepherder in 1989, the Basque community has not had the opportunity to take part in a national initiative of this scale—one dedicated to recognizing its wartime service and shared sacrifice on American soil.

The National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial is not conceived merely as a list of names, but as a space that acknowledges lives, families, migration journeys, and a shared sense of responsibility shaped by war.

An invitation to be part of history

As the project enters this new phase, community participation remains essential. This Memorial is the result of a collective effort—one that depends on individuals, families, and organizations who believe that this history deserves a permanent place in the American landscape.

Supporting the Memorial—whether through donations, sharing its story, or participating in upcoming events—means taking part in a historic moment.

Those who wish to support the Memorial may do so through our secure online donation page:

https://my.cheddarup.com/c/national-basque-wwii-veterans-memorial/items

If you prefer to contribute by check, donations may be sent to:

N.A.B.O. WWII Veterans Memorial Fund

c/o Mayi Petracek

11971 S. Allerton Cir

Parker, CO 80138

Additional information about the Memorial and the campaign can be found here:

https://nabasque.eus/wwii_memorial.html

Your contribution to support the Memorial is tax-deductible Educational Fund of North American Basque Organizations Inc. (EIN: 82-0489192). All donors making a donation in excess of $1,000 will be publicly recognized on a Donor wall unless they choose otherwise.

The February 13–14 events are more than an announcement—they are an invitation to take part in a historic moment, and to help shape a memorial that belongs to us all.

Together, we can ensure that the service and sacrifice of WWII veterans of Basque descent are honored, remembered, and passed on to future generations.