|

Hasiera · Home |

|

Ezaugarriak · Features |

|

Oharrak · Notes |

|

Sarrera · Introduction |

|

Euskara |

|

Folklore |

|

Kirolak · Sports |

|

Musika · Music |

|

Janedanak · Gastronomy |

|

Tokiak · Places |

|

Historia · History |

|

Politika · Politics |

|

Diaspora |

|

Internet |

|

Albisteak · News |

|

Nahas Mahas · Misc |

For security reasons, user contributed notes have been disabled.

by Martin Hardie

| Martin Hardie (Maputo/Durango) is a bit of a nomad. He has managed bands, worked in Aboriginal Art centres, been a solicitor, a barrister, an advisor to various members of the former East Timorese resistance, and a university lecturer. He currently spends his time as a moderator of the nettime list, undertaking his post-graduate research work and fulfilling his duties as a correspondent for www.cyclingnews.com. His ambition is to become the archetype of life within communism at the break of dawn a cyclist, during the day a cook, cyber-conspiracist and correspondent, in the afternoons a student and philosopher and, at nights, simply pleasant company. See his homepage at http://auskadi.tk/. |

Of course, the phenomena of which I speak is La Marea Naranja, the Orange Tide, the legions of Basque fans who inundate and claim the Pyrenees as their own for at least one weekend in July. Sitting back at home listening to Phil and Paul, I am sure that many wonder why do these crazy Basqueys appear so much more passionate and committed than your average TdF punter. Sure, we see supporters from other places, flying their flags or their team colours, the Flemish Lions, the Danish Cross, the boxing kangaroo. Who can forget that summer in the nineties when the King was dethroned and the route seemed to be populated by blond-headed, red- and white-painted Danes singing endlessly and wildly out of tune “Bjaaaarne Riis, Bjaaaarne Riis, Bjaaaarne Riis…..”. But you have to admit those crazy Danes were mild mannered and few in number in comparison to the Orange Tide.

The appearance of the Orange Tide coincided, of course, with the participation of Euskaltel-Euskadi in the Tour de France. But the question remains: how did such a small team, then just bubbling out of the Second Division, manage to enthuse such a mass of emotion and support, to cause the Pyrenees to come alive with the sound of orange in such a way? When you see these scenes it is like the whole population of the Basque Country has turned orange and moved on mass to the TdF.

In their first appearance at the Tour in 2001, even the Euskaltel riders themselves were surprised at how passionate and how numerous their fans were. David Etxaberria told me afterwards that to rise through the Orange Tide was “a great sensation; it gives you goose bumps” But the truth was that “we were not expecting it at all until we passed them”. Etxebarria described the Orange Tide as a “grand fiesta of Basque cycling,” and it is here that the explanation of the phenomena lies: that cycling allows the Basque people one way of expressing who they are, their identity and their difference. Being together, in a group and enjoying life and a grand fiesta, is a large part of being Basque. |

With an area no bigger than Tasmania, the Basque Country can boast over 70 riders in the European pro peloton this year. Many of them have passed through the ranks of what is now Euskaltel-Euskadi. Cycling is an expression of their difference, their local habits, their ways of doing things and their love of the grand outing. But when many people think about things Basque, their immediate thoughts are not positive; car bombs and ETA come to mind before the many gems of Basque Culture such as cycling, pelota and pintxos.

David Etxebarria sees a link between the place of sport in Basque culture and the legacy of the Franco years. “Sport is a part of Basque culture, and because of the suffering and sacrifice it has more influence, is more deeply rooted than in other cultures. It is because of the repression through which we have lived.” As a people who felt strongly about their identity, the Basques suffered heavily during the civil and war and the Franco years. Durango, Euskaltel’s “home town,” and Gernika where the first civilian populations to be bombed from the air. And, during the Franco years, the Basque language, an indigenous European language that predates the Romanisation of Europe, was banned.

Sport has been, and continues to be, one of the ways that the Basque people can express their identity without being “political.” In fact it appears that cycling has played an important role in helping the Basques remain Basque during the last seventy odd years of attempts by Madrid to make them more Spanish. The great rivalries of Spanish cycling of old -- Bahamontes and Loroño, Bahamontes and Ocaña -- all in one way or another were ciphers for the Basque’s feeling of Basqueness. A feeling that Etxebarria says means “to be proud of one's country, one's people and one's culture …” he continues “you don’t have to be born here to be Basque, but what is important is that you feel Basque”.

To feel Basque is to first and foremost live the gregarious, social way of loving life that they have. It is for many, like David Etxaberria, not about thinking of the Basque Country “as a country within another country” but as “a country within the world..." as a place in its own right whatever the geopolitical reality. The "...the team thinks this way and it is for this reason we are in the team”. But the geopolitical reality is that the Basque Country is within Spain and for most Basques this legal fact doesn’t decide anything -- they are and they feel Basque. Nevertheless, when Basque riders race in events such as the World Champs or the Olympics they race as Spaniards. Two current world champions, Igor Astarloa and Joanne Somarriba, are both Basque. Only in surfing has this little corner of Europe managed to gain recognition for their national federation.

Over the years a number of great

Basque cyclists have been the objects of national passion. They have

in one way or another assumed or had hoisted upon them the symbolism

of a national identity. From the days of Jesus Loroño, to the

first generation of post Franco riders such as Julian Gorospe and

Marino Lejarreta, cycling has carried with it a meaning of being more

than just sport. During the years of the transition to democracy,

Marino Lejaretta was probably the first cyclist to be explicit about

his Basque identity. Of course this was not possible before the

dictators death. Lejaretta had an impressive string of

victories: the Classica San Sebastian in 1981, 1982 and again in 1987,

and the Vuelta in 1982. Late in his career he was third in the

’91 Classica San Sebastian behind none other than Miguel

Indurain. It was then Indurain who became the successor to the

symbolism embodied by Lejaretta.

Until the end of Indurain’s reign, this humble Navarran farm boy can probably be said to have prompted the most overt expressions of Basque imagery and symbolism ever seen outside of politics or to have been focused upon one sportsman. Being Navarran, a part of the traditional Basque lands, made it possible for him to be adopted by the Basque community. Wherever Indurain rode, the distinctive Basque flag, the Ikurriña, dominated the routes.

With the passing of Indurain and with his win in the World Champs of 1995, Basque hopes were passed on to Abraham Olano. Of course in recent years we have seen a literal explosion of Basque pros in the upper ranks of the peloton, most notably Joseba Beloki, Igor Gonzalez de Galdeano and World Champ Igor Astarloa. But it was during this time of the mid nineties that Basque cycling took a new turn and, with it, the feeling of being Basque gradually shifted focus from being personified in one great hope -- a cycling cult of the personality -- to being embodied in a team that would be proudly and outspokenly Basque.

|

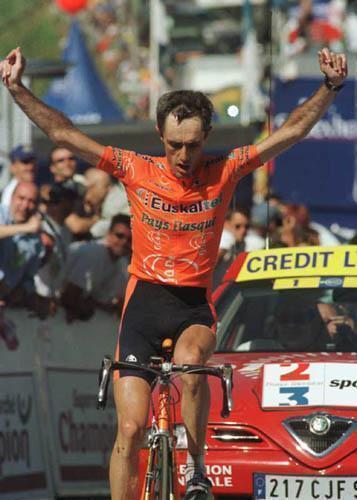

The team Euskadi (Basque Country) entered the professional ranks in 1994 and, unlike every other professional team, they displayed no sponsorship logos, only the red, green and white colours of the Ikurriña. While picking up a number of victories each year, it was with the entry of the Basque telephone company, Euskaltel, that the team’s fortunes really took off and they hit the international stage with their debut appearance in the TdF. With this debut, the colours of the Ikurriña were still present in the team’s kit, but it was the bright orange of the sponsor that took centre stage. And it is this orange that has in a way become the fourth national colour. In these times of ongoing tension between Madrid and the Basque country orange has become a metaphor for all things that are embodied in the spirit of being Basque. When Roberto Laiseka charged up Luz Ardiden to victory ahead of Armstrong and Ullrich in the 2001 Tour, he was carrying more than his own weight. As he rode through that incredible sea of orange clad fans and waving Ikurriñas, he carried with him, and rode through, a grand fiesta and all that which symbolises the incredible lightness of being Basque. Laiseka still rides with the chance of winning a stage or two, but the focus of the team has passed to the younger generation of Iban Mayo and Haimar Zubeldia, and Euskaltel have now set their sights a fair bit higher than picking up a few more stage wins. |

|

Please report any problems or suggestions to Blas. Eskerrik asko! |