Below we publish the chronicle of the latest trip of Dr. Pedro J. Oiarzabal – co-author of this blog and co-principal investigator of “Fighting Basques: Memory of World War II” – to the United States. His trip’s goals were two-fold: to disseminate the nearly-final results of the research, on the tenth anniversary of the projects beginning, on the Basque participation in the American ranks during the last world conflict; and to deepen the work developed to date in the achievement of a monument, on American soil, to the memory of these soldiers.

The Choice of Identities

The American West is the place where the hopes and dreams of thousands of Basques for generations and generations were born.

On my latest trip through Idaho and Nevada, as well as on the numerous others I have made for nearly a quarter of a century, I continue to be amazed by the depth of the Basque legacy in the American West, both in the construction of its imagery and in all the different facets of its society. The extraordinarily positive image of this legacy, which the various Basque-American communities and their institutions enjoy today, very likely does not correspond to its real weight. It is, however, an intangible heritage of incalculable value, and if managed well, it could help strengthen the future of this historic and complex American diaspora, while also enabling its members to continue choosing to connect with all things Basque.

Between the hyperbolic public image of Basque identity generated by the Jaialdi festival in Boise, Idaho – the largest Basque festival in the United States – in its eighth edition (July 29 to August 4, 2025) and the more modest annual Basque picnics in Mountain Home, Idaho and Gardnerville, Nevada, both held on the weekend of August 9 and 10, lies in some ways the situation, closer to reality, in which the Basque communities of the American West find themselves.

The Basque diaspora, whether in the United States or in any other country, historical or recent, is a vast chain in which every link is necessary for its very existence. This is also true at the local and community levels. In the postmodern identity market, choosing to identify with the Basque identity in the diaspora is similar to a small salmon struggling against the current to reach its final destination. Connecting with Basque identity and culture means contemplating the importance of the small things in life, shaped by time and the legacy of one’s ancestors, and enjoying them before they fade away irreversibly.

The American West is also the place where the descendants of those Basque emigrants who left their homes weave together, day after day, transformative complicities of the present, rooted in a distant past, and filled with unpredictable and uncertain futures. Each generation struggles to prevent everything they knew and loved from vanishing, while every action and decision they make leads them to transform their memories into present-day projects for future generations. In every dance step, in every musical note, in every bertso, and in every bite of food lie the seeds of a Basque identity laden with memories and recollections that honor the vision and actions of their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents, in keeping their historical and cultural legacy alive.

Recognize and Honor World War II Veterans of Basque origin

For a decade, the non-profit Sancho de Beurko Elkartea has led the research project “Fighting Basques,” the first systematic academic study of the contributions of Basques and Basque Americans to the U.S. Armed Forces and Merchant Marines during World War II (WWII). This is a pioneering study, both in the Basque Country and in our immediate geographic context, on the role played by a minority emigrant group and their descendants up to the second degree (grandchildren of emigrants) in the last world conflict under the American flag. It is, in fact, a history of the United States during WWII through a Basque lens.

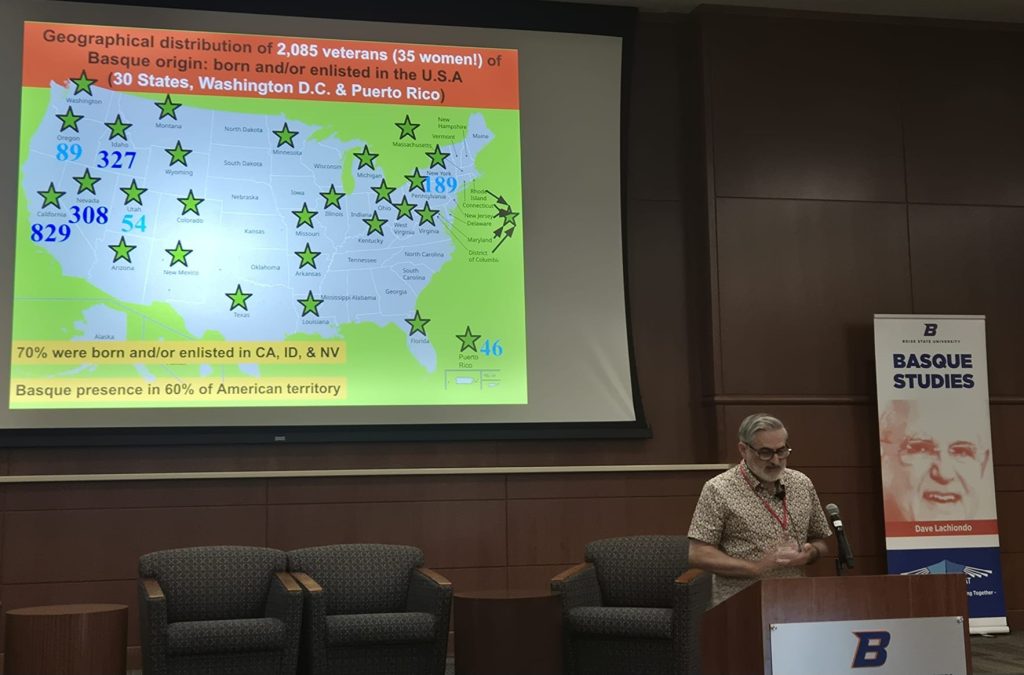

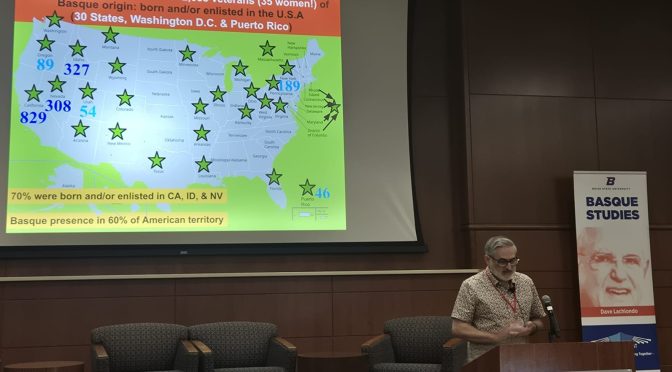

Once the study was almost completed, I had the honor of presenting its main results in Boise during the International Symposium on the Basque Diaspora “Zortziak Bat” (at Boise State University) and in Reno, Nevada at the Nevada Historical Society.

Month by month, year by year, we have been putting together the pieces of the hitherto largely unknown puzzle about the Basque and Basque-American contributions to the U.S. military forces during WWII. Today, we have identified nearly 2,100 men and women of Basque origin, born and/or enlisted in 30 states, as well as Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico – which represents 60% of the country. Even so, 70% of them were born and/or enlisted in California, Idaho, and Nevada. (It is not surprising to find that these three states are home to the majority of the U.S. population of Basque origin today.) These 2,100 soldiers served in all branches of the military and fought on all fronts.

Furthermore, nearly 270 of these soldiers were born in the Basque Country. More than half of them were not U.S. citizens at the time of their enlistment, which speaks to their true commitment to their adopted country. Despite their participation in WWII, unfortunately many of them would not achieve citizenship.

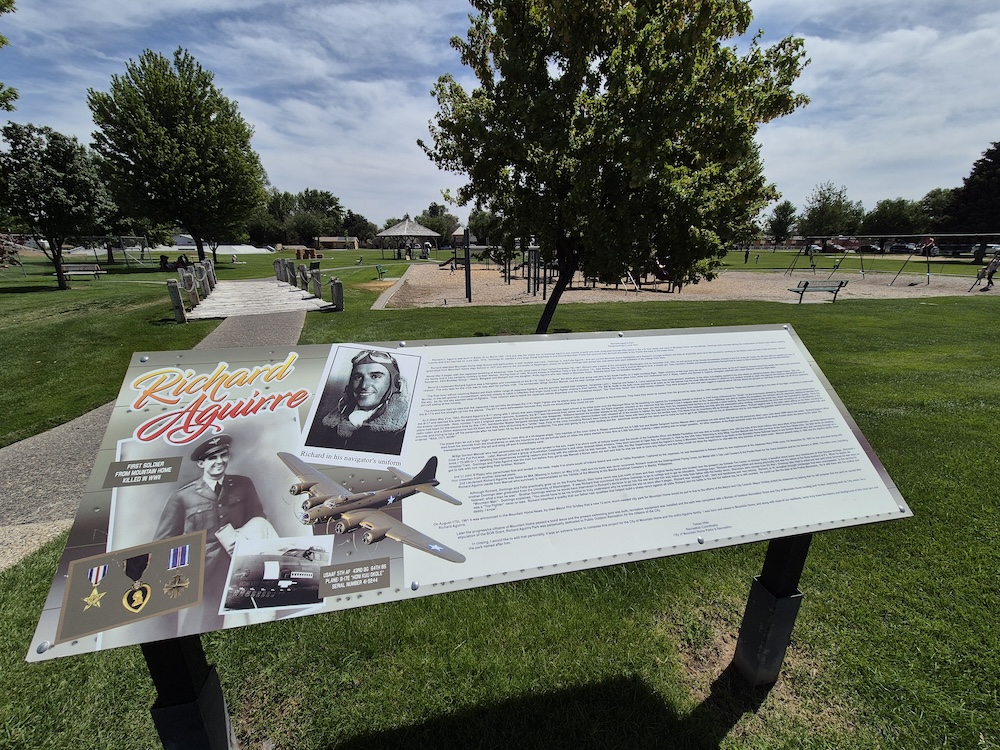

At the beginning of our research, very little, if anything, was known about the Basque participation in WWII under the U.S. flag, and even less about the number of soldiers identified to date. They were simply shadows in oblivion. It is “the greatest generation,” but also the most unknown, one that had gone unnoticed by the academic world and remained alive only in the memories of their closest relatives. Without a doubt, the most cherished moments of my trip have been related to the encounters with the children, nephews, or grandchildren of our veterans, whether in Boise, Elko (Nevada), Reno, or Gardnerville.

If the dozens of relatives I was able to speak with during my short stay in the country had one thing in common, it was their desire to demand a place for their veterans in our public history, in our collective memory. Their veterans survived the Great Depression and stood up to authoritarianism and fought for democracy, for many of them to the bitter end. This is why their families are demanding immediate public recognition.

And this is exactly what we, under the leadership of the North American Basque Organizations (N.A.B.O.), are working on, to build an official commemorative memorial on American soil to permanently honor their memory and sacrifices, with the intention of inaugurating it by the end of 2026, coinciding with the 85th anniversary of the U.S. entry into the war.

Finally, before my trip came to an end, I visited the small cemetery of the California town of Coleville, in Antelope Valley, where I paid a small tribute to three veteran brothers, whose father was Basque and whose mother was Native American, and who are part of a little-studied chapter of Basque history in the American West.

There are not many Basque-Native American veterans who participated in WWII, but they tell a story of understanding between seemingly very separate cultures, but undoubtedly very close in their experiences of nomadic life, dispossession, and extreme survival in the deserts and high-altitude mountains of both Nevada and California.

I would like to remind you that N.A.B.O. has launched a fundraising campaign with the aim of building the National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial in honor of all WWII veterans of Basque origin.

To achieve this goal, we need your help. It requires all of us – individuals, companies as well as public institutions – to make this worthy initiative a reality.

DONATE NOW! Don’t let veterans be forgotten!

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Greetings,

I cannot speak about the future of the Basque culture in the U.S.A. But I know that in the Bearn, a province in France, close to the Spanish/French border, the Basque culture is very much alive, shared and welcome.

When I opened my inbox this afternoon, there was the Bearnais blog I belong to. The word of the month in addition to various activities going on in September. For a fiesta, Sautejada, there was a flag composed of 2 vaquetas ( cows ) representing the Bearnais flag and the Ikurrina. . It is written in French and some Basque. The meaning of the title is “lets dance, share culture and life together”.

This exchange of sharing life, culture together with our neighbors is our daily life, not just during fiestas. Europe will keep the Basque culture going through thick and thin.

Monique