Ardiak beeka egonik, ez du jaten belarrik.

A bleating sheep eats no grass.

These proverbs were collected by Jon Aske. For the full list, along with the origin and interpretation of each proverb, click this link.

Ardiak beeka egonik, ez du jaten belarrik.

A bleating sheep eats no grass.

The three Basque cities I’ve spent the most time in are Donostia, Munitibar, and Ermua. My dad’s sister and her family settled in Ermua as that is where the job was – her husband worked for the knife company Aitor until he retired. Ermua maybe doesn’t have the charm of the coastal cities, but it has its own unique marcha and, like so many Basque towns, a vibrant street life. The Basque tradition of the txikiteo is strong there, leading to the creation of some unique and spectacular pintxos. Not every city can be a tourist trap. Ermua is a town where the people just live their lives.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Ermua, Wikipedia; Ermua, Wikipedia; Castaño García, Manu. ERMUA. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/ermua/ar-40057/

This article was written by Pedro Oiarzabal.

Martin, born on July 4, 1925, in Las Arenas, Getxo (Bizkaia), was one of the thousands of children evacuated by the Basque government in June 1937 to escape the aerial bombardments perpetrated by General Francisco Franco’s Italian and German allies against the civilian population. Martin and two younger brothers were sent to Belgium. At just 12 years of age, he became the head of his family during their exile and through the harsh times of World War II. In May 1940, Germany invaded Belgium. The Aguirres once again found themselves in the middle of a war.

During that last world conflict, Martin became an active member of a clandestine network in Belgium aiding and rescuing Jews from the Nazi regime. Despite being in his late teens, he saved the lives of a considerable number of children and teenage Jews. On January 11, 2011, Yad Vashem—The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority—recognized Martin as one of “The Righteous Among the Nations.” He is one of the very few Basques recognized in this way.

Aguirre’s biographer, Dr. Pedro J. Oiarzabal, describes him “as a humble man of great integrity and honesty.” “I am proud to call him my friend,” the Basque diaspora specialist said. “As an oral historian, I began a series of interviews with Martin back in 2014 and we have stayed connected as much as possible through the years. I am still thanking him for agreeing to be interviewed and for narrating his life, which included some very painful moments and memories, which I will always treasure and protect.” Dr. Oiarzabal concludes, “we owe him so much for making this world a freer and better place under the very difficult circumstances that were World War II. We will forever be in his debt.”

Happy birthday, Zorionak, Martin!

Ardi txikia, beti bildots.

The small sheep, always a lamb.

It is seemingly part of human nature that we most vehemently attack that which is somehow a part of us. Pierre de Lancre was no different. One of the most infamous persecutors of Basque witches, he himself had Basque ancestry, an ancestry that his family seemed to deny. De Lancre felt that all aspects of the Basque culture reflected the inherent tendency of Basques toward evil.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Arozamena Ayala, Ainhoa; Elia Itzultzaile automatikoa. Lancre, Pierre de. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2025. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/lancre-pierre-de/ar-84793/; Pierre de Lancre, Wikipedia; Pierre de Lancre, Wikipedia

Ardi galdua atzeman daiteke, aldi galdua berriz ez.

One may recover a lost sheep, but not lost time.

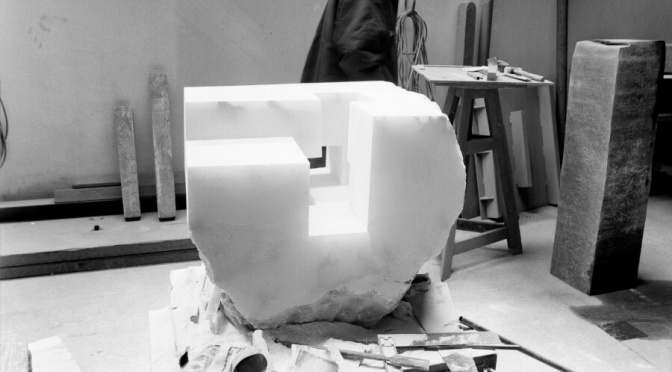

One of the aspects of Basque culture that has always fascinated me is the mix of tradition with the most cutting edge ideas. Growing up in the Basque communities of the American West, I was exposed more to the traditional aspects of the culture – the dancing, the singing – and less to the avant garde that seems to define much of modern Basque culture, such as the radical rock. Basque art is no different, with some of the most important artists working in abstract spaces that, while feeling counter to the ancient traditions, are still rooted in them. Perhaps the most famous Basque sculptor, Eduardo Chillida epitomized this dichotomy.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Zabalaga-Leku. Hernani; Elia Itzultzaile automatikoa. Chillida Juantegui, Eduardo. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/chillida-juantegui-eduardo/ar-36023/; Eduardo Chillida, Wikipedia

Apaizaren eltzea, txikia baina betea.

The priest’s pot is small, but always full.

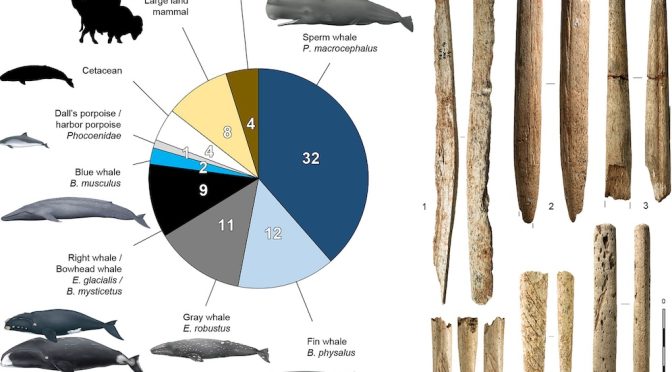

Basques have long been associated with whaling. Records as far back as 670 highlight the importance that whale hunting was to the Basque economy and their way of life. However, the people that inhabited the region we now know as the Basque Country used resources from whales even earlier, many millennia earlier. New research has revealed that people on the coast of Bizkaia and the surrounding regions made tools from whale bones some 20,000 years ago.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary source: McGrath, K., van der Sluis, L.G., Lefebvre, A. et al. Late Paleolithic whale bone tools reveal human and whale ecology in the Bay of Biscay. Nat Commun 16, 4646 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59486-8