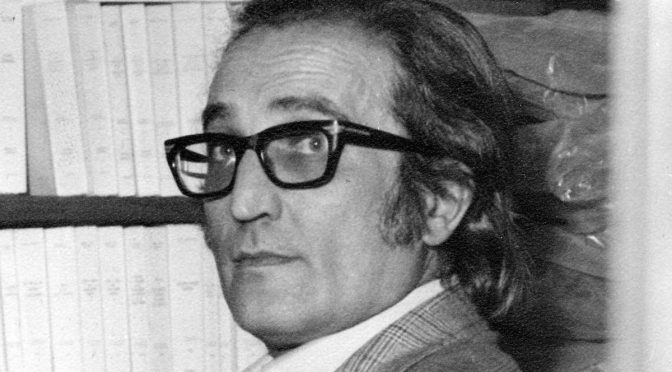

Not growing up in the Basque Country and not being exposed to the history and culture on a daily basis, there is so much I simply don’t know, so many figures that made an impact on the culture that I’ve never heard of. Gabriel Aresti is one of those. While I’ve heard his name in connection with a poem or song, I had little appreciation for his contributions. And, with so many things associated with the Basque Country, Aresti as a figure is complicated. His importance to Basque culture is undeniable but his politics make him controversial for some.

- Gabriel Aresti Segurola was born on October 14, 1933 in Bilbo. While his father spoke Euskara, he only did so with Gabriel’s grandparents, so Gabriel grew up with Spanish as his first language. However, he learned Euskara on his own, starting when he was 12 years old, and he wrote primarily in Basque.

- When he was 21 years old, he published his first poems in “Euzko-Gogoa” in Guatemala. He soon became known to the Basque public and by 1957 was a correspondent for Euskaltzaindia, the Basque Language Academy. A few years later he began winning prizes for his work, first for his poem “Maldan behera” and then his play Mugaldeko herrian eginikako tobera.

- Aresti is most well known for his works Harri eta Herri (Stone and Country, 1964), Euskal Harria (The Basque Stone, 1968) and Harrizko Herri Hau (This Country of Stone, 1971). This series of “stone” (harri) works, linking stones to the Basque people and culture, delves into the lives of the people of the Basque Country. His poems, which “take place in an urban environment and are written in free verse” were praised for “their modernity, innovative spirit and their left-wing humanism” (source). Perhaps his most famous poem “Nire aitaren etxea” appears in Harri eta Herri. Because of his controversial ideology, it took some time for Aresti to find a publisher for Harri eta Herri.

- In addition to his original works, Aresti also made significant contributions to Basque literature through translation. He translated the works of several authors to Basque, including Federico García Lorca, T. S. Eliot and Giovanni Boccaccio. Anecdotally, he was working on a translation of James Joyce‘s Ulysses when the Guardia Civil raided his home and confiscated the manuscript – it was never seen again.

- Aresti became a major proponent for the unification of the Basque language. He used both colloquial language and an early form of a unified Euskara in his works.

- Near the end of his life, he became a publisher, establishing the publishing house Lur. Several important Basque authors got their start with Lur, including Ramon Saizarbitoria, Arantxa Urretabizkaia or Xabier Lete. However, Aresti’s own work, Kaniko eta Beltxitina, was censored by his colleagues and friends at Lur and so he broke his association with the publisher.

- His ideas, often sympathetic with communism and class struggle, put him at odds with both Franco’s regime and with the nationalist parts of Basque society. For example, one of his talks was interrupted by a group of young Basque nationalists who accused him of diluting the Basque nationalist struggle by promoting a more general class struggle. He became strongly associated with communism, which for some tarnished his contributions.

- He died in 1975 at the age of 41.

- Some of his work has been translated into English.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Gabriel Aresti, Wikipedia; Gabriel Aresti, Wikipedia

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.