Conducted in Fall 2007

Guillermo Zubiaga is a graphic artist living in New York, though he was born and grew up in the Basque Country. We met through my website, when Guillermo contacted me about a link to his site. In this interview, Guillermo describes growing up in post-Franco Euskal Herria, his experiences in the US comic book industry, and his current project about a comic book on the history of Basque whaling.

Buber’s Basque Page: Please tell us a little bit of your background. Where are you from? Where do you live now?

Guillermo Zubiaga: I was born in the year 1972 in Barakaldo, Greater Bilbao, Bizkaia, the Basque Country, Spain. When I was 5 years of age my family and I moved from the industrial city to the idilic Basque countryside, to the town of Laukiniz in the Mungialdea-Plentzia region of Bizkaia.

About Guillermo:

I was born in the year 1972 in the greater Bilbao city area on the Basque province of Biskay, Spain.

When I was 5 years of age I moved with my family from the industrial city to the idyllic Basque countryside. At the age of 18, I traveled to the U.S.A.

Today I live in New York where I work as an illustrator and Graphic Designer. Prior to this I attended my senior year of High School at DeSoto High School in DeSoto , Texas. After High School I went to Syracuse University where I graduated in 1996 with a Bachelor degree in Fine Arts. The year before graduation I began working for a local animation studio, Animotion, inc. The following year after graduation I moved to New York City where I started my work “ghosting” in the comic books industry. After a relative period I successfully managed to find credited work drawing as an assistant penciler for Marvel comic’s X-Force. In 2003, I began working as an inker on such comic books as Dark Horse’s B.P.R.D. and Image’s The Romp.

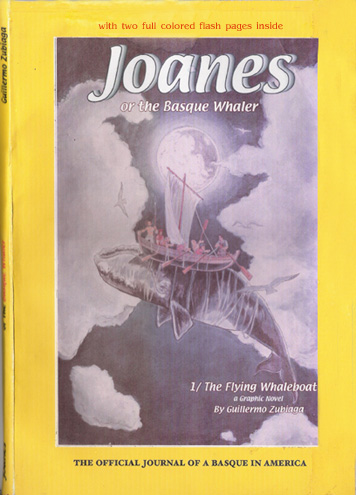

I have recently finished my own graphic novel based on traditional Basque whaling.

Since 2004 I have been working in the apparel industry as a designer for companies such as Freeze and Changes. In addition to that I combine traditional fine art in drawing, painting as well as new technologies such as Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, Flash, or HTML, with being a College level History and Art History teacher and lecturer.

Visit Guillermo’s website at www.guillermozubiaga.com.

Today I live in Long Island, New York.

BBP: What was growing up Basque like for you? How did being Basque affect your childhood? Do you speak Euskara?

Guillermo Zubiaga: It was only 3 years before Franco’s death and the end of his dictatorship that I was born and, even though at such an early age I was not aware of it, I clearly remember going to an “underground” Ikastola my first school year when I was in kindergarten. I remember this quite vividly because the Ikastola was but a few classrooms literally underground in the basement of a local cafe. In the morning our parents would drop us off covertly and, once inside the “cafe,” we would have to pass underneath the bar’s counter to the other side of it and, through a hidden trap-door on the ground, we would descend to the underground basement classrooms. (It was something almost out of the movie “Carlito’s Way” when he makes his escape through the hidden passage…) It was but a few years later that I truly began to realize the sacrifice and the big risks my parents took for us.

Later on after Francos’s death, with the legalization of Ikastolas and after we moved to the countryside, I really began to identify much more closely with the Baserria lifestyle as the bedrock of Basque identity and the repository of our unique culture in the face of advancing urbanization and industrialization.

Today, even though I live in the United States, I make a point to pass on our heritage by teaching Euskera to my son.

BBP: Your experiences going to school to learn Euskara are amazing. I knew it was a hard time for the Basque language, but I didn’t realize those kinds of things were going on. You and your family risked a lot so you could learn Euskara.

Given your experiences, what does the Basque language mean to you? How do you view the role or place of Euskara in Basque culture? Can the Basque people survive as a unique culture without the language?

Guillermo Zubiaga: In spite of it all, I think that there is no doubt that I truly consider this particular aspect of our culture to be at the very core of our identity. Naturally beyond any political ideology (and excusing all those Basques who for whatever circumstances were unable to learned it) for me Euskera is at the epicenter of our character. Therefore, the role of Euskera in Basque culture is an integral part of our singularity. This is along with (and in close second place) our capacity to be guided by our own sense of destiny, the reflection of which can be seen in the creation of a unique sociopolitical structure, the Fueros. The Fueros are an elemental and masterfully crafted sense of compromise between absolute political independence and loyalty to whom ever would respect our own laws in exchange for self-rule, sovereignty or autonomy.

Indeed for the Basques, as with so many other “foreign” concepts such as feudalism, its lineage and/or its entire structure of nobiliary hierarchy had to be adapted as time went by as Basques came in contact with such things. In relation to many of these concepts, such as the “universal chivalry or gentlemanliness” of all Basques, we can notice how this became expressed in the very “Fuero” as it was adapted to a concept from the outside.

All of this is equivalent to the sense of belonging to a Country (Territorialidad) versus kinship (Gentilidad) since the first concept did not appear (or it did not began to be applied or to acquire a practical use) until the coming of the Romans to Euskal Herria. According to the records of the classic authors (Stabro, Silo Italico, Ptolomeo, etc, etc) who placed much more importance on the concept of kindred or “tribal” affinity than on the sense of territory. It is here, and specifically from “within,” that we find a deeply rooted distinction, from the point of view of kinship and in particular linguistic connection, between the own language (euskera) and the other (erdera). This is the grounds or basis for a marked transcendence in order to understand the relations between the “Basque” (from the purely linguistic sense) with other peoples (and naturally other cultures…)

In other words, first the names such as vascones, vardulos, caristios, aquitanos etc, etc appeared and later we begin to see the development of geographic or political demarcations such as Vardulia, Vasconia, Aquitania etc, etc. And much later, and first by means of the Vascones and later through the influence of the kingdoms of Pamplona and Navarra, we begin to see names such as Bizkaia or Gipuzkoa etc, etc, respectively.

And of course, in my opinion, without the strong and specific identity of the land at the very fore front of which I must place Euskera, neither the Basque Country collectively nor the individual historical territories such as Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, Labourd, Navarra etc, correspondingly would exist.

With out the Basque language, the Basque Country and its historical territories would be anything else but………

BBP: Considering the important role that Euskera has in Basque identity, then, how do you see the future? Especially with globalization, immigration, and all of the pressures that small nations such as Euskal Herria experience, how can the Basque language survive and thrive in the modern world? Are you optimistic about the long-time viability of the language?

Guillermo Zubiaga: I think that, given what Euskera has gone through its history, we can acknowledge without fear of being wrong that our beloved Basque language is currently going thought perhaps one of its most prosperous periods, enjoying as it does official status within the Autonomous Community of Euskadi as well as, but in a lesser degree, in that of Navarra. I believe there is some work to do in Iparralde…..

The Basque language has proven itself to be more than ready to face the challenges of the future, and fortunately, with an approximate figure of 600,000 speakers, it no longer belongs to the “endangered species list”. In 1643, the Basque Scholar Pedro Agerre “Axular” in his book Gero said:

Baldin egin baliz euskaraz hanbat liburu, nola egin baita latinez, franzeses, edo bertze erdaraz eta hitzkuntzaz, hek bezain aberats eta konplitu izanen zen euskara ere, eta baldin hala ezpada, euskaldunek berèk dute falta eta ez euskarak.”

(As many books could be written in Euskera as in Latin, French or as many other languages, since Euskera is as rich and satisfactory of a language as these others, and if that has not been so the blame should not go to the language itself but to those who speak it.)

The Famous American cinematographer and friend of the Basques, Orson Wells, in his film The Land of the Basques, stated that Basques are not worried about the future since we figured we have survived this far so we will continue to survive. It “is a kind of sense of dignity and being close to each other, proud of the past, easy on the present, and not afraid of the future”.

Therefore I believe that the best way for our language to survive is for us to continue using it, just as the old Basque ode reminds us:

“Hizkuntz bat ez da galtzen dakitenak ikasten es dutelako baizik eta dakitenok erabiltzen ez dutelako”

(A language is not lost when those who don’t know it don’t learn it but when those who know it don’t use it.)

It is up to us to continue to pass it on to the new generations, and that way we discover the positive signs that strengthen our identity and our linguistic consciousness.

BBP: From your point of view, does the Basque Country, however one might define it, need to be an independent entity for Euskera to thrive, or can it do so within a situation like the current arrangement in Spain and France?

Guillermo Zubiaga: As far as the need for the Basque Country to be an independent entity for Euskera to thrive, in my opinion I don’t think is an absolute necessity. Our language has survived in spite of the Basque Country not being an independent State. Besides, being part of the European Union, matters such as independence, borders, currency etc don’t seem to have the same outlook and significance as years ago. On the other hand, in essence, and except for international or foreign relations, the Basque Country already functions practically as an independent State within the Spanish State, controlling its own budget pertaining to finance and financial matters, especially of the local autonomic government and taxes. Not to mention an unparalleled self-rule unseen in any of the countries belonging to the EU, well above the German Landers, or even the Swiss Cantons (not in the EU).

I think deep down the pro-Independent option in the Basque Country has a lot to do with pride and the urge to be recognized internationally or the lack of presence in international events, etc. I myself already know what I am, I don’t need of a flag at the United Nations to determine whether or not I belong to a sovereign people.

Furthermore look what happened in Ireland with their Gaelic language, for example. Soon after their independence they seemed to be so content with their new “status” that it appears as though they no longer have the same impetus to vindicate their language or claim responsibility for it and, as a consequence, the status of the Gaelic language I would say is in no better place as before their independence. Since they already are an independent State, it seems as if the weight to justify their language has lessened in precedence and passed to be relegated to a less significant role. I believe this, thanks to a great numbers of Irish friends who wether here in the States or back in Europe: none or very few show the same bond to their language as the majority of Basques do, certainly not in terms of its use given the significant differences between both populations.

But that is just me; maybe being far away from home for such a long time has made my mind open up to the world. As a youngster, I had no doubts towards my pro-independence, but today I am perhaps more cautious. Then again, even though I am not one of those who is pushing for a referendum, if that referendum was to come, I’d probably vote in favor.

BBP: Tell us about your work. You are a graphic artist, working in particular in the comic book industry. What projects stand out for you? What are you working on now?

Guillermo Zubiaga: When I was 18 I came to the United States and after completing High School in Texas I attended school at Syracuse University where I graduated in 1996 with a Bachelor degree in Fine Arts. The year before graduation I began working for a local animation studio, Animotion Inc. A year after I graduated, and shortly after I moved to New York City, I started my work “ghosting” in the comic book industry.

After some time, I successfully managed to find credited work drawing as an assistant penciler for Marvel Comic’s X-Force. In 2003, I began working as an inker on such comic books such as Dark Horse’s B.P.R.D. and Image’s The Romp.

Since 2004, I have been working in the apparel industry (t-shirts, sweaters, swing trucks, etc) as a designer for different companies through out the NYC area. I still get to draw a lot but I also spend a great deal of time on the computer finishing the artwork (I taught myself a great deal of computer applications which I found to be very helpful considering how fast the world spins…..)

In addition to being a designer and illustrator, in the last 6 years I have supplemented my creative activities with being a college-level History and Art History teacher and lecturer. I have stayed relatively connected to the comic book industry and I have recently finished my own graphic novel about Basque whaling, which happens to be a favorite subject of mine. Originally, and since I had made some connections in the industry, I thought it would be easy to have it published. However, most editors are interested in having a secure and established “core” market and since anything to do with Basque is so little known, let alone the people, imagine our whaling history……So go figure. Ultimately I’ll probably have to self-publish it in very small runs and distribute it myself through conventions or by offering it to a number of whaling museums through out Long Island and/or New England, Rhode Island, Connecticut, etc… Yet, I still hope the project gets picked up since this is really the one project that best reflects me and, I think, stands out for me.

In all truth this project has been a very personal work that I have chosen to do out my own restlessness and personal interest on the subject. I always felt that for us Basques, the whaling period, the fisheries in Biscay and Newfoundland, are very important national symbols, which come to represent a heroic age, or a “western” period unique to our own idiosyncrasy, equivalent to the cowboy to the Americans, the viking to the Scandinavians or the samurai to the Japanese. This subject also casts a very insightful light on the late medieval period, the Renaissance and early American exploration, which in my opinion is a much more beautiful and interesting content. Hey! After all, the oldest written document in North America is in Euskera (the testament of XVIth Century Basque whaler Johanes de Echaniz) so this topic is not only a part of Basque history but American as well! (Quite an irony, though. Since the last will never made it back, no body saw a dime of his will, yet again, if that would have been the case, today we would not have an invaluable piece of history and the undisputed evidence of early Basque presence in North America.)

BBP: I remember those issues of X-Force! They had some great art. I knew the name Adam Pollina, who I guess was the main artist on those issues, but never realized an Euskaldun was involved. That is really cool. And I definitely look forward to seeing your graphic novel published. I can see your point about the Basque whaling sort of being the Basques’ “American West”, especially in that it was an epic period of their history, but it also has a dark side, I guess especially viewed with today’s sensibilities.

It has been hard for you to get a work that focuses completely on the Basques to get published. I am wondering if comics can be used in other ways as well to promote Basque culture. For example, could you envision a super-hero that had a strong Basque identity? From your experience, is there a way that American comic books can be used to promote Basque culture?

And, does the Basque Country itself have any kind of graphic art-form culture? Is there a role for comic books or comic strips in the Basque Country? If not, could this be a vehicle to promote the Basque culture from within in a novel way?

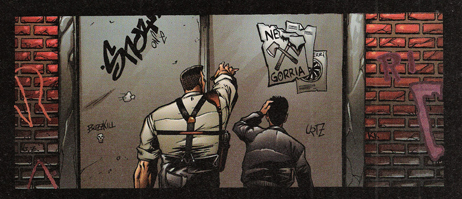

Guillermo Zubiaga: Indeed X-Force had some great art, in fact it was my friend and mentor in the comic book world, Adam Pollina, who bolstered the sales of that particular title when it had been declining for a while. I became involved “ghosting” on the series X-Force(the name “ghosting” is given because the artist’s work goes uncredited and therefore while his or her work exists, his or her presence is “unseen”) on issue 75 but it wasn’t until 79 that I finally got recognition for my work by getting credited on the books. So from issues 75 to 78 I added lots of subtle (and not so subtle) details, throughout the backgrounds: a lauburu here, a Basque Rock band banner there, a E.H. sticker over there (only to find out much later that in NY E.H. stands for East Hamptons,…oh well!!). Since I knew I wasn’t going to get recognition, I tried to add my own personal details by leaving, should we say, an unmistakable Basque mark.

I find the comic book industry to be highly competitive and difficult, so it has been hard to get work, period. Let alone work that focuses on or promotes a Basque theme. I often ponder that comics can be (or should be) used in ways to promote culture, and this means Basque culture as well, or any other culture for that matter. Unfortunately, I have grown very skeptical of the “educational” use of any media these days overpowered by a devastating and purely entertaining and commercial objective.

As far as envisioning a super-hero with a Basque identity, as much as I would love that (especially if I was to get such a privilege), I see that extremely difficult in the mainstream. That is why alternative medias are so important and that is where my own character (Joanes, the Basque Whaler) comes in, even though he is not a super-hero, nor even a hero. He is more like the archetypical anti-hero, sort of the Han Solo character, or the “Man with no name” played by Eastwood in Sergio Leone’s “spaghetti westerns”, which is, coincidentally, at the center of the influences surrounding my book.

From my own experience, if there is a way that American comic books can be used to promote Basque culture, that is at the core of what I am trying to do. I’d love to introduce some “Basqueness” into the American comic book world and the fact that it hasn’t happened yet is no deterrent for me to be discouraged. In all truth, I did my graphic novel out of my own personal experience and interest and, of course, because I always felt that for us Basques, the whaling period, the fisheries in Biscay and Newfoundland, are very important symbols. On the other hand, I always wanted to pitch an idea to Marvel about a story with Wolverine (since he is the only character old enough for the subject, nothing to do with the fact that he is my old time favorite) during 1936-1937 as a participant in the Spanish Civil War as a Canadian agent with the international brigades in Euzkadi, fighting along Gudaris on the iron belt, or liberating Paris with the Gernika Battalion!

As far as Basque comic books right now, or the role of comic books in the Basque Country, I know of (although not personally) the work of Lopetegi and Alzate, who apparently have been very active and are currently causing quite a stir. I think they deserve it since this is quite a life of sacrifice. Bejondeizuela you two!! However, I remember, when growing up in the Basque Country, two brilliant adaptations to comic books on Navarro Villoslada’s Amaya and the Basques of the VIII century (in both Basque and Castellano) as well as the famous Battle of Orreaga. Both were very limited runs sponsored by local banks or “Aurrezki Kutxa”s (cajas de ahorros) so are very hard to find, yet they are more my “cup of tea” since they deal with “historical” themes.

BBP: I never noticed those Basque touches in X-Force. I’m going to have to dig my issues out of storage and look at them again. That is very cool. As do those two Basque comics. I wonder if there is a way to get them on the internet now? I imagine that there are a lot of Basque topics that would be great for a comics adaptation, like the Song of Roland from the Basque point of view. Have you ever considered doing something like a web comic with Basque themes?

Guillermo Zubiaga: You’ll be surprised what you can get on the internet this days. Here is the URL of the editorial that publishes the work of Basque artists such as Raquel Alzate: www.astiberri.com/a_cruzdelsur.asp.

About the “Song of Roland” from the Basque perspective, that was one of those comic books which I told you about, entitled Roncesvalles in Spanish or Orreaga in Basque. Nevertheless I consider it to be nothing short of exceptional and I would love to get my hands on a copy of it.

As far as doing a web comic with a Basque theme, that is something that I have thought about. In fact my next “personal project” which I am currently developing is animating my graphic novel as a Flash movie to be broadcast over the web as an interactive comic. But then again, just like with the actual drawing and inking of my graphic novel, which I did in my spare time, this comic “adaptation for the internet” is going to require the same amount of that precious commodity, time.

BBP: You’ve mentioned a number of projects you are working on or would if you had a lot more of that commodity, time. What are your dream projects, either in the main stream comics industry, personal projects, or other media?

Guillermo Zubiaga: Indeed I have too many projects I am either working on or would like to develop further if I only had more time.

I would love to see my graphic novel finally published and/or finished as a movie. Once I have that in “the can,” I would love to present the whole project as a multimedia exhibit; the book, the movie projection and the gallery of the original artwork (as well as the thousands of sketches…) on the walls. Other than that, I would like to put together a book on Iberian Mythology, which of course includes Basque mythology.

And why not! The children’s book market is one that I still have to venture in…..

BBP: Being so far from the Basque Country, how do you keep the Basque culture in your life? How do you pass on your culture to your family?

Guillermo Zubiaga: As far as how I keep the Basque culture in my life being so far from the Basque Country as I am, I have been a member of the Euzko-Etxea of NY since 1998, where I go often and get to speak in Euskera to lots of different Basques from the tri-state area (NY, NJ, CT) or simply be in a Basque context outside of the house. On the other hand, my brother-in-law, the father of my niece and nephew, is from Donostia and I speak with him as well as with his son and daughter exclusively in Euskera on an almost daily basis. For his part he does the same with me and my son (his nephew). We also happen to be each other’s kid’s godfathers.

Besides the daily use among us, and as well as between my son and myself, I read a lot in Euskera: books, online articles, newspapers. I also spend some time writing in Euskera almost on a regular basis. In addition to that I listen to Basque Music (if not exclusively, quite a lot!!). Of course a big part of that music I play to my son who happens to take to it very kindly.

BBP: What Basque groups do you listen to? I just discovered Buitraker and am always looking for more great recommendations. What type of Basque music do you listen to? Folk, punk? Any recommendations?

Guillermo Zubiaga: I am very eclectic when it comes to music. My Ama is a classical trained Doctor in music who teaches at a Conservatory of Music and plays several instruments, so at a very early age I was exposed to classical stuff, specially Wagner and (according to many, his Basque counterpart) Francisco Escudero.

But as far as groups and or Basque Music I like to listen too, I would include the following: ROCK (punk and “ska-Hardcore”): Hertzainak, Kortatu, Baldin Bada and many of the so-called Rock Radical Vasco scene from the 80’s.

As far as PUNK rock, which I happen to like quite a bit, I honestly think that two of the best PUNK bands (in the world) to come out of the Basque country (even if they sing in Spanish) would be Eskobuto (Santurtzi) and more recently Lendakaris Muertos (Iruña).

I even like Basque “reggae and Rap” with Negu Gorriak and Fermin Muguruza.

Basque HEAVY METAL with bands such as Su ta Gar or EH Sukarra or even Urtz (some of whom I got to meet when they came to NY, in fact, I actually had the chance to sit next to them on the flight back to Europe). Then, there are very cool bands that mix Rock with traditional Basque instruments such as the alboka (without a doubt one of my favorite sounds, gives me Goosebumps!!!) such as Exkixu. I also like the classics such as Benito Lertxundi, Oskorri, and of course Mikel Laboa, and rock folk artist such a Ruper Ordorika.

I love the modern and international takes on Trikitixa and Txalaparta of Kepa Junkera and Oreka TX respectively (the last I also met last November when they stopped and played at the Euzko-Etxea as part of their visit to NY to promote their new movie Nomadak TX).

A few years back I discovered a really cool band by the name of Bidaia (before they were a quartet, now a duo) which combines alboka, with zarrabetia (hurdy-gurdy), ttun-ttun etc with guitars and other “normal” stuff, really good!!

I hope I am not leaving anyone out (although I probably am…). Certainly, I recommend every single one.

My son likes Kids Classics such as Pintxo-Pintxo, Paristik Natorre, Txirri, Mirri ta Txibiriton and the sound track of Dotakon (euskeraz).

You can find many of these in YouTube and as far as Basque lyrics you have this link: eu.musikazblai.com.

BBP: Eskerrik asko, Guillermo!

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “An Interview with Guillermo Zubiaga”