This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario. You can find all of the English versions of the Fighting Basques series here.

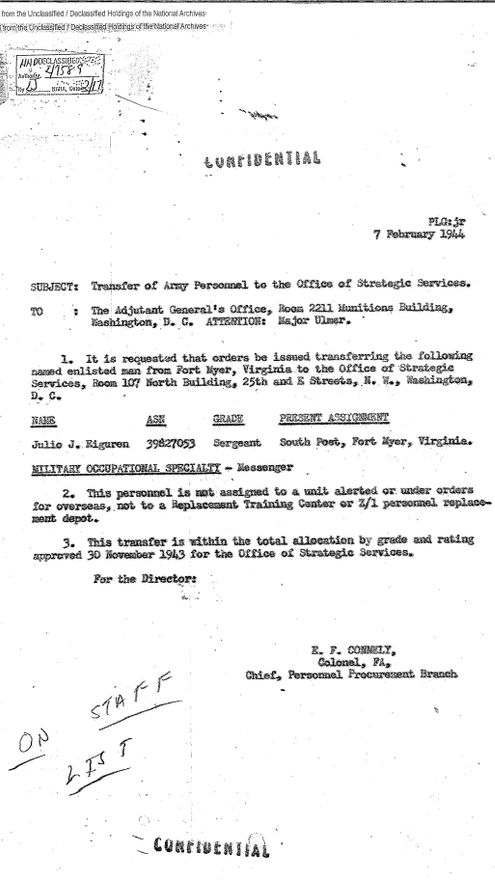

The invasion of Burma (now Myanmar) – in the hands of the British Empire since 1886 – by the Empire of the Rising Sun at the end of December 1941 was another strategic military coup of great importance against the power of the allied powers in the Southeast Asia. The British would capitulate in April 1942, with Burma becoming a key player on the military board of the Japanese in a final attempt to subjugate China and gain prominence in the region. While the Basque-Nevadans of the US Air Force – Joseph Malaxechevarria Plaza, Santy Arriola Onandia, John Montero Bidegaray, and Domingo Arangüena Bengoa – heroically flew over the skies of Burma, on the extremely dangerous route between India and China, at the end of 1944 in the south of the country, a secret agent of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) – the first centralized intelligence agency abroad in the history of the United States (USA) – was deployed: Julio Eiguren Bermeasolo, born in 1919 in Jordan Valley, Oregon, to Biscayan parents. Two years before the creation of the OSS, on April 13, 1942, Eiguren had enlisted in the army in the city of Boise, Idaho. For two months he attended the Military Police Replacement Training Center at Fort Riley, Kansas, which was established in April 1942 to train soldiers and military police for replacement of losses abroad. On June 8 he would be transferred to the South Post, Fort Myer, Virginia. His military occupational specialty was “messenger.”

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

Despite being a very young organization, established only in June 1942, the OSS expanded rapidly, albeit with difficulties and to different degrees of penetration, through the different theaters of operations, with the exception of the Pacific which had been sharply vetoed by General Douglas MacArthur. (Later in 1944 and 1945, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz would make use of the pioneering OSS maritime unit in the invasion of the Philippines.) After the liberation of France and the stabilization of that theater of operations, the priority of the OSS immediately shifted to Germany, and after the end of the war in Europe to the Asian front. Excluded from the army and navy controlled sectors of the Pacific, the OSS devoted all its efforts to the distant China-Burma-India Theater, largely unknown to the public and regarded as the “forgotten war” of World War II (WWII). While the OSS staff assigned to that region did not reach 14% in October 1944, between June and September 1945 the region held 36% (about 4,000 people) of the total agency staff. It was the “ideal” terrain – sparsely populated with dense jungles, and a devastating monsoon climate plagued with tropical diseases – for the kind of unconventional warfare behind enemy lines that the OSS had perfected in Nazi-occupied Europe. In this way, for the first time, the OSS sent abroad a first detachment of special forces, formed by sections of special operations and secret intelligence, called “Detachment 101,” which operated in the north of Japan-occupied Burma between April 1942 and 1945. The OSS had about 800 Americans and a guerrilla force of about 10,000 indigenous natives (about 9,000 Kachin who formed the “Kachin Rangers”) instructed by the American agency to deal with the Japanese imperial troops.

Similarly, the OSS formed “Detachment 404” whose operational area primarily covered southern Burma, the Arakan coast (with a strong presence of the Muslim Rohingya minority, armed and trained by the British); the south of French Indochina (Cambodia and southern Vietnam), Siam (now Thailand); Malaysia; and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). The “404,” officially identified by the nickname of the “US Experimental Division”, was active for 21 months. It was formed by about 200 agents selected from the commandos of the operative groups, the intelligence section and the maritime unit, which acted between 1944 and 1945, with the help of Malaysian agents trained by the OSS in the United States. The headquarters of the “404” was located in Kandy (then British Ceylon, today Sri Lanka), where the Headquarters of the Allied South East Asia Command was located between 1943 and 1946, led by British Admiral Louis Mountbatten and US Lieutenant General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, who jointly coordinated their actions (unlike the “101” which retained its tactical autonomy). On February 14, 1944, Eiguren was transferred from the army to the OSS, receiving highly specialized training to serve abroad. On November 23, 1944 he was assigned to the “404”.

Despite the close relations between the OSS and the Basque Government in exile, and particularly between its director, General William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan and the Lehendakari José Antonio Aguirre, the incorporation of Eiguren, and other Basque-Americans, occurred outside of this collaboration. The potential of an entire generation of young Americans of Basque origin who would join all the different branches of the US Army and on all military fronts during the course of WWII went incomprehensibly unnoticed by the Basque Government itself and its intelligence service. How many military units, exclusively Basque, could have been formed had they had hundreds of Basque-American recruits? It is particularly in the context of the 75th anniversary of the constitution of the Gernika battalion, the only Basque combatant unit in WWII, where the inquiry into the reasons behind the non-use of the Basque-American contingent by the Aguirre government becomes unavoidable.

One of the sections of the OSS that stood out, along with that of secret intelligence and special operations, was the Task Force Command (comparable to the special forces unit of the British Army, the Special Air Service (SAS) founded in July of 1941), responsible for the selection, training, equipping and activation of resistance groups in guerrilla warfare (a kind of “secret army”); for select discretionary attacks; and for surprise combat operations, limited in scope, by small special forces units. These commando units – uniformed unlike their companions in special operations – were made up of immigrants with command of foreign languages resident in the United States or by second-generation Americans who had retained their mother tongue. Most of its members were recruited from the armed forces. Native populations, ethnic or religious minorities were extolled and empowered in an effort to mobilize different populations in favor of the Allies, whether they were the “Kachin Rangers” or the failed Basque commandos of Rothschild (or Airedales) [1].

For example, among the operational groups, OGs, that served in France, those made up of French, Norwegian Americans or Italian-Americans stood out. By 1944, the OG had 2,000 men, including Germans, Greeks, and Yugoslavs (the OSS trained both partisans of the Communist Party under the leadership of Josip Broz “Tito” and the Chetniks, nationalist and anti-communist guerrillas loyal to the monarchy, of General Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović), and Thai or Chinese anti-colonialists (the latter in 1945). As can be seen, the formation of exclusively Basque operational groups would not have been strange at all since it followed the OSS’s own idiosyncrasy.

According to the military file requested from the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Eiguren worked for the “404” Services Section as a “courier” or “dispatcher,” although his “special ability” was that of an “aircraft worker” without mention of the missions in which he took part. The messaging service (“courier”) consisted of handling the transmission of highly classified documents, for which very high caliber personnel were hired, their work being vital for communication between the various components of the detachment. In a very few months Eiguren rose very quickly, from private to sergeant.

Among other activities, the “404” mapped the Arakan coast (full of mangroves), compiled thousands of intelligence reports, reported on Japanese submarines, helped rescue downed Allied pilots, infiltrated enemy territory, carried out dozens of sabotage missions, and organized numerous and successful operations in Thailand, including the formation of a Thai guerrilla force (some of them, students in American universities, were trained by the OSS in the USA) that did not go to war due to its immediate end. The “404” also collaborated with agents and guerrillas of the Ho Chi Minh Viet Minh in Vietnam, provided them with weapons, medicine and training, and carried out their own missions in Vietnamese territory. With the capture of Rangoon on May 2, 1945, Burma was largely liberated from Japanese occupation. The actions taken by the OSS made it easier for Thailand to maintain its sovereignty after the war, under the orbit of American foreign policy, and away from the old colonial pretensions of the United Kingdom.

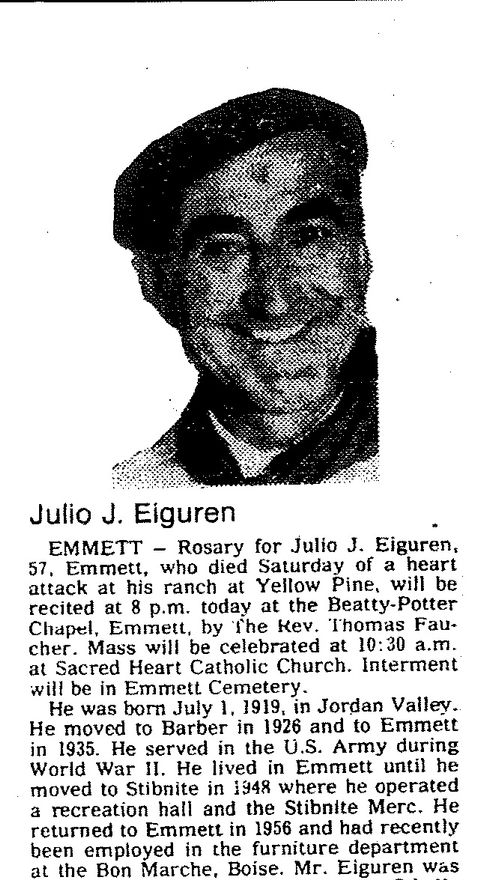

After nine and a half months of service in Burma, Eiguren ended his work with the OSS on November 6, 1945, as part of the general demobilization program for American troops. Upon his return to the United States, he was transferred to Fort Meade, Maryland, on November 14, where he was discharged from the army. He died of a heart attack on his ranch in Emmett, Idaho, on August 7, 1976 at the age of 58. For the general public, Eiguren was another soldier in the army who served his country with honor abroad. But in reality he was a secret agent whose work in the OSS “Detachment 404” is unknown, and whose contribution to the end of the war on the Southeast Asian front was completely unknown. According to his superiors, “Sergeant Eiguren was one of the most exceptional soldiers in this Detachment” with excellent physical abilities, leadership skills and motivation, among other qualities. For the rest of the world, Eiguren was never in Burma.

[1] Oiarzabal, Pedro J. and Tabernilla, Guillermo. “The enigma of myth and history: ‘Basque code talkers’ in World War II. The OSS and the Basque Information Service — the Airedale Organization.” Saibigain Magazine, No. 3 (2017). “The enigma of myth and history:‘ Basque code talkers ’in World War II. The OSS and the Basque Information Service — the Airedale Organization “

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.