This article originally appeared in Spanish at EuskalKultura.eus on July 23, 2021.

Faced with the legend and the myth of Carranza and his group of “Basque code talkers,” the real events of those Americans of Basque origin, Basque of flesh and blood, with Basque names and surnames, have to be vindicated by Basque historiography as the actual subjects who are from our diaspora and from our common history.

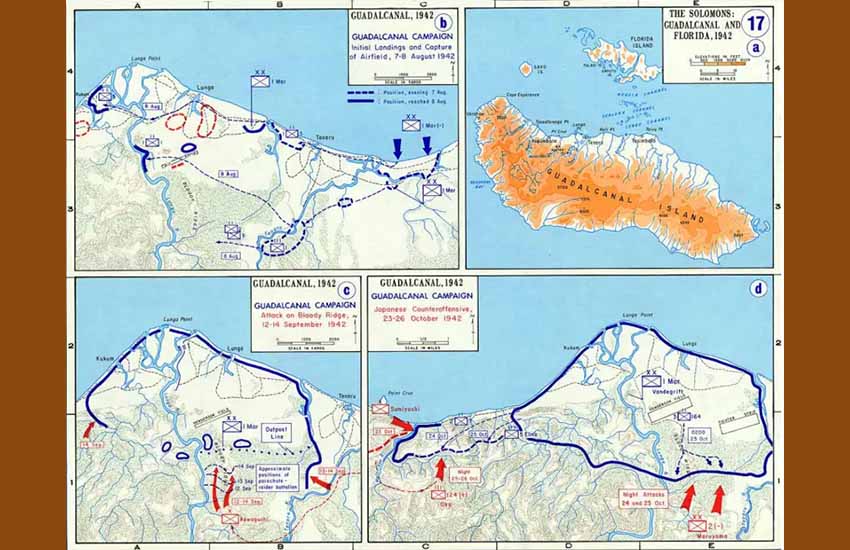

Legend tells of how the mythical captain of the United States Army, Ernesto or Frank Carranza, apparently in command of a group of sixty formidable US Marines of Basque origin – all of them the sons of sheepherders from California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada and Oregon – supposedly helped conquer Guadalcanal Island, located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, in the summer of 1942.

These young men – Basque soldiers trained in broadcasting at the beginning of the Second World War (WWII) – would have carried out tasks as “code talkers” or coders, apparently using Basque as a secret code to transmit military orders, including the landing in Tulagi on August 7, 1942 and thus confuse Japanese listeners.

Decades later, on April 25, 1979, an article signed by Vicente Escudero in the Basque newspaper Deia summarized this epic under the title “110 Basques and 90 Andalusians conquered Guadalcanal in 1942.”

That article not only increased the number of Basques who, according to legend, initially took part in the battle for Guadalcanal; they were also joined by a similar number of Andalusians – we suppose that since the island was baptized as such in 1568 by the expeditionary Pedro Ortega de Valencia, a native of said Sevillian town – and revealed, strictly exclusively, the death of the enigmatic Basque-Mexican Captain Carranza on April 22, 1979 in a fatal hit-and-run in New York.

However, this legend – as fascinating as it may be – is certainly just that, a legend, a myth. With the exception of the fight that took place between the troops, mostly between American and Japanese troops for the strategic control of Guadalcanal, none of the above story is true.

If you wonder how a leading newspaper like Deia – which was joined by all kinds of publishers, including from academia, and many other media outlets in disseminating and deepening this myth for decades – took for granted the story that young Basque and Andalusian soldiers took Guadalcanal; the military use of codified Basque; the very existence of the supposed Carranza; and to make matters worse, the final notice of his death – they will discover that hoaxes, propaganda, misinformation or “fake news” were not born with Twitter.

After dismantling the myth of the “Basque code talkers” a few years ago, and trying to illuminate the reasons for its birth within the framework of the relations between the Basque Government in Exile, of the Lehendakari José Antonio Aguirre, and the Office of Strategic Services of the United States, of Colonel William Donovan, it is only fair that we recognize “the other Basques,” those who did participate in the Guadalcanal Campaign, and who unfortunately were overshadowed and marginalized by the unusual myth of the use of Basque in Guadalcanal [1].

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

Who were the real Basques of Guadalcanal?

In this article we reveal the identity of some of these true heroes, unknown until now, that we have been discovering during the progress of the “Fighting Basques” research project. The Historical Recreation Group of the Sancho de Beurko Association has joined the commemoration of the 79th anniversary of Guadalcanal and has given us their help to visualize it.

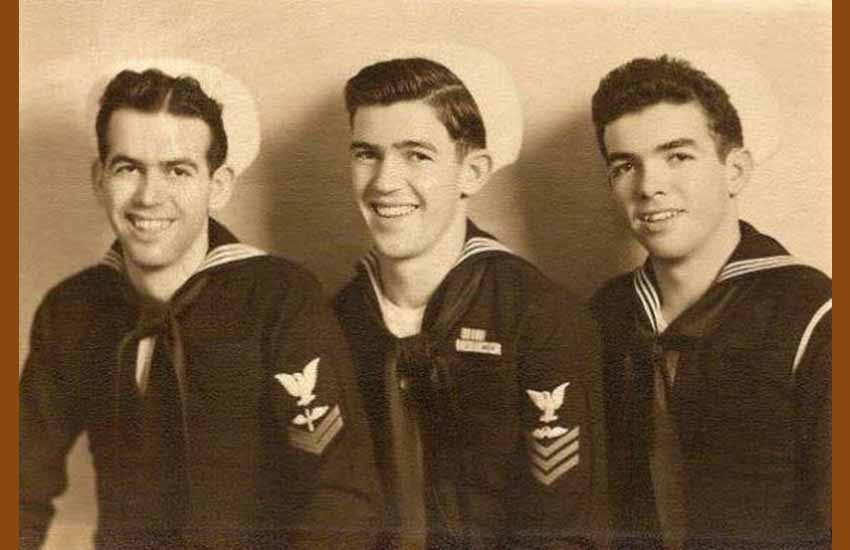

Among the “Fighting Basques” of the Guadalcanal Campaign, or “Operation Watchtower,” we find people like John Facque Elissalde, John Sallaberry Berra, Henry Etchemendy Hauscarriage, Joseph Quintana Ybáñez, Domingo Amuchastegui Guenaga, John Maitia Urbelz, John Basañez Basteguieta, James Miguelgorry Souhilar, and Joaquin Juanche Muñoz.

All of them were protagonists of “Operation Watchtower,” which lasted for six long and bloody months, from the beginning of the invasion on August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943, approximate date of the end of the evacuation of the last Japanese troops who resisted on the island.

The Guadalcanal Campaign became the first US amphibious offensive in a new Allied military strategy to dominate the Pacific Theater of Operations. Since December, 1941, the military expansion of the Empire of Japan across the Pacific seemed unstoppable until the Allies conspired to end it. And they did so on the hitherto almost unknown Guadalcanal Island.

In January, 1942, Japanese troops had landed in the Bismarck Archipelago, located between the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. They later occupied Kavieng in New Ireland and Rabaul in New Britain in Papua New Guinea. Rabaul would become Japan’s main military base in the Southwest Pacific.

In March, the Japanese seized Salamaua and Lae in Papua and Bougainville, the largest island in the Solomon archipelago. A couple of months later, the Japanese were in Tulagi where they began the construction of a seaplane base.

Between May and July, the Japanese forces continued their expansion throughout the rest of the Solomon Islands.

On June 8, they landed in Guadalcanal, where a month later they began to build an airstrip near the mouth of the Lunga River.

For the Allies, this posed a fearsome threat against the allied air base of Espiritu Santo, located in the New Hebrides archipelago. This development also endangered the communication routes between the US, Australia, and New Zealand. It was imperative to neutralize it [2].

On August 7, 1942, 8 months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, US Marines landed at Tulagi, Florida, Tanambogo, Gavutu, and Guadalcanal. After defeating the Tulagi and Guadalcanal garrisons, they took over the port of Tulagi and the Guadalcanal airstrip, which they christened “Henderson Field,” finishing its construction on August 21 [3].

From the coast, the US fleet provided cover support for the initial amphibious assault, which came under heavy enemy air fire. On board the USS President Hayes, an attack transport, was the young Basque-Nevadan, of Nafarroa Beherean parents, John Facque. The mission of the USS President Hayes was to land units of the 2nd Marine Regiment on the northeast side of Guadalcanal.

On the ground, among the marines of the Second Division we identified the Basque-Nevadan Henry Etchemendy. Etchemendy, also of parents from Nafarroa Beherea, served in the 10th Regiment, providing artillery support from the beginning of operations.

The Guadalcanal Campaign had just begun, leading to numerous land and naval battles over the coming months, with significant aerial skirmishes.

From Rabaul, the Japanese launched air strikes against the American forces deployed in Tulagi and Guadalcanal, which were joined by attacks by the destroyers and light cruisers of the Imperial Navy, while supplying their troops on the ground as best they could.

The shortage of food and military materials would be a general trend for both the Allies and the Japanese, although it would be noticed with much greater impact among the Japanese troops.

The clashes between Japanese and American patrols were constant, while sporadic Japanese attacks of greater magnitude took place, such as the one that occurred between October 23 and 26, 1942, which aimed to recover the airstrip now known as “Henderson Field.”

Among the American reinforcements sent to Guadalcanal during the beginning of autumn, there was, for example, the light cruiser USS Boise. On board we find Joseph Quintana – born in 1917 in Nevada to Nafarroan parents. The mission of the USS Boise and the soldiers like Quintana was to give cover during the landing of a new wave of marines in Guadalcanal.

The USS Boise was damaged during the Battle of Cape Esperance on the night of October 11-12 and would have to return to the US for repairs. Quintana passed away in Sacramento in 1979.

The USS Boise was joined by the escort carrier USS Copahee, which moved fighters and torpedo boats bound for “Henderson Field.” Domingo Amuchastegui, born in 1923 in Nevada to Bizkaian parents, served aboard the Copahee, where he was in charge of repairs to the structure of embarked aircraft.

John Maitia, a Marine of the 14th Aircraft Group, landed on the island in October 1942.

Maitia, whose father was from Nafarroa Beherea and whose mother was from Nafarroa, was born in California in 1922. He took part in the so-called Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, another attempt (again unsuccessful) to retake Henderson airfield, with an important deployment of the Japanese Navy and a large number of Japanese troop reinforcements from Rabaul.

The reinforcements sent by the Americans to repel this new counteroffensive were attacked by Japanese airplanes on November 11 and 12.

The naval battle was a victory for the Allied side after days of heavy fighting, ending on November 15.

It was Japan’s last and greatest attempt for “Henderson Field.”

Maitia passed away in 2018 at the age of 95.

The marine Facque was aboard the cruiser USS Northampton when it was sunk by Japanese torpedoes at the Battle of Tassafaronga on November 30, 1942, in an effort to prevent the Japanese from reinforcing their troops at Guadalcanal. Facque was unharmed and survived the sinking.

He died in 2015, at the age of 93.

In December, 1942, two other Basque-Californians arrived at the Guadalcanal front: the soldier John Basañez and the “seabee” James Miguelgorry. Basañez, of Bizkaian parents, served in the 185th Regiment (Regimental Combat Team) of the 40th Infantry Division, facing Japanese troops from the first minute. At Guadalcanal he fell ill with malaria, which he carried for the rest of his life. He passed away in South San Francisco in 2001.

Miguelgorry was born in 1918 to parents from Nafarroa Beherea. He served in the 18th Naval Construction Battalion, which was assigned to the Second Marine Division, for reconstruction duties. Miguelgorry’s unit was outfitted with Marine uniforms and equipment. He passed away at the age of 81 in Washington State.

At the beginning of 1943, the Marine of the Second Division, John Sallaberry, and the soldier of the 161st Infantry Regiment, Joaquín Juanche, arrived at Guadalcanal. The Basque-Californian Sallaberry, of a Lapurdian father and a Gipuzkoan mother, served with the 6th Regiment, which disembarked from the USS President Adams in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area. Juanche, born in California in 1915 to Nafarroan parents, was involved in bloody fighting in defense of the positions around “Henderson Field.” He also participated in the elimination, from January 10 to 21, of a concentration of Japanese troops in what became known as the Matanikau River Pocket, a dense redoubt of jungle situated between a steep hillside and a high cliff above the Matanikau River.

Like Etchemendy, his compatriots Sallaberry and Juanche also fought until the end of the Guadalcanal Campaign.

From January 10 and for about two weeks, the US troops began an offensive to eliminate the Japanese forces from the island, in which the 161st of Juanche participated very actively.

Sallaberry will obtain the Silver Star for his heroism in an action that took place on January 21 in Guadalcanal.

During a patrol with his platoon several hundred meters beyond their defensive lines, an enemy machine gun wounded one of his comrades. Sallaberry, with the help of another marine, picked up the wounded man under constant enemy fire and without regard for his own safety. After Guadalcanal, Sallaberry, Etchemendy and Juanche, together with their comrades in arms, would continue the fight in the southwestern Pacific.

Sallaberry passed away in 1990 and Etchemendy in 2001.

Unfortunately, Juanche was killed in combat at the age of 27 on August 5, 1943 in New Georgia.

The losses, both human and material, were substantial for both sides, although evidently the balance turned to the Allies. About 30,000 Japanese soldiers out of a total of 36,000 perished in the Guadalcanal Campaign, most of them as a result of famine and tropical diseases.

After Guadalcanal, Japan found itself on the defensive for the first time since Pearl Harbor, unable to replace the air and sea fleet destroyed during the long Guadalcanal Campaign.

The allied counteroffensive continued through the rest of the Solomon Islands and New Guinea, capturing Japanese bases of enormous strategic importance, which would facilitate success in future campaigns in the southwest and central Pacific.

The historical narrative presented here arises from verifiable evidence and imposes itself on the myth and its undeniable power of seduction, which to date had falsely connected the Basque with the remote island of Guadalcanal during WWII, masking the true events carried out by Americans of Basque origin, of Basque flesh and blood.

The legend of Carranza and his group of “Basque code talkers,” and its promoters in the shadows, are left with as their only refuge the passing of time, the forgetting of history as it happened and its true heroes.

These heroes must be reclaimed. Facque, Sallaberrry, Etchemendy, Quintana, Amuchastegui, Maitia, Basañez, Miguelgorry and Juanche – among others that our investigation can still reveal – must be indisputably vindicated by Basque historiography as active subjects of our diaspora and of our common history.

We owe it to them and to their memory if we want history to impose itself on myth.

Thus, is necessary more than ever to create a future with memory; a public, didactic and inclusive memory.

Notes

(1) Oiarzabal, Pedro J. and Guillermo Tabernilla. “El enigma del mito y la historia: ‘Basque code talkers’ en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. La OSS y el Servicio Vasco de Información—la Organización Airedale”. Saibigain, No. 3 (2017)

(2) Mueller, Joseph N. (1992). Guadalcanal 1942: The Marines Strike Back. Oxford: Osprey Publishing

(3) Danny J. Crawford, Robert V. Aquilina, Ann A. Ferrante, Lena M. Kaljot, and Shelia P. Gramblin. (2001). “The 2nd Marine Division and its Regiments”. Washington D.C.: History and Museum Divisions Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”

If you get this post via email, the return-to address goes no where, so please write blas@buber.net if you want to get in touch with me.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.