This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario on November 27, 2019.

“The air attack on the airfields of the main island of the Philippines, Luzon, took us all by surprise and the ‘P-40’ fighters were destroyed on the ground the first day, without being able to take off.” Thus begins the first-person account of Román Arruza Asorena – a young US Army soldier recruited in Manila while he was studying dentistry at university – published in 1988 by José Miguel Romaña in his book La Segunda Guerra Mundial y Los Vascos. It was December 8, 1941. The 14th Army, under the orders of Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma, began the invasion of the Philippines in the context of Japan’s military and colonial expansionism in East and Southeast Asia. Arruza, born in the city of Iloílo, on the island of Panay in the Western Visayas region in 1920, was the son of prominent sugar and tobacco farmer Román Arruza Urrutia, from Mungia (Bizkaia). As a child, the family moved to Durango (Bizkaia), but the beginning of the military uprising in 1936 pushed them into exile, first to France, and then to the Philippines.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

Following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, only a few hours before the Philippines was attacked, the Japanese carried out a campaign of multiple and successful attacks on American, British and Dutch possessions. During the months that the Battle of the Philippines lasted, Japan invaded Guam, Burma, British Borneo, Hong Kong, Wake Island, the Dutch East Islands, Dutch Borneo, Java, Singapore, Sumatra… it wasn’t until the beginning June 1942 that Japanese ambitions met their first major setback, at the hands of the United States (USA), with the victory at the Battle of Midway.

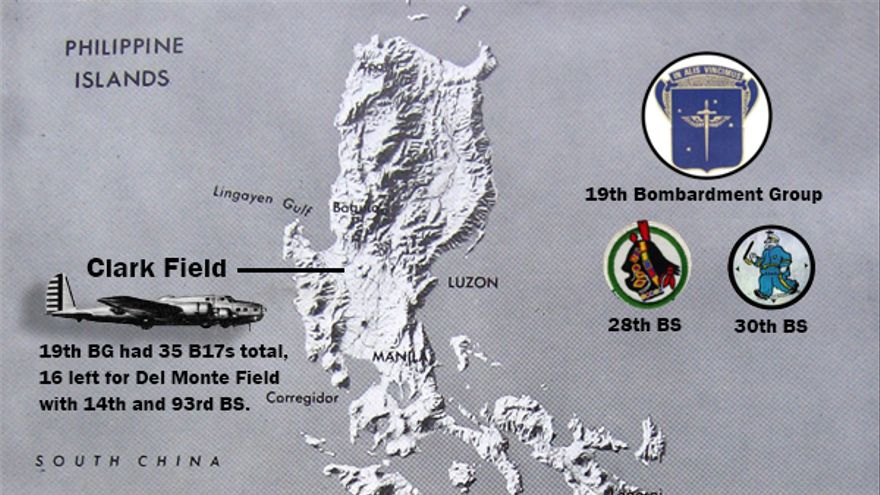

At that time, command had decided to transfer air groups to the Philippines to improve their defenses in the Pacific, among which were the 19th Bombardment Group (B-17) and the 27th Bombardment Group (A-24). The relocation operation of all the B-17s that were in Hawaii and California had not been completed when the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. Similarly, the 27th arrived in Manila on November 20, 1941. Faced with the Japanese invasion of the Philippines, the priority was to divert convoys for transporting supplies and airplanes to Australia, while the pilots and all valuable military personnel, who were on Philippine soil, were evacuated.

Among those who were en route to the archipelago, we have identified James Larronde, of both Nafarroa Beherea and Bizkaian origin. James was born in 1917 in Los Angeles, California. Graduating as a pilot in October 1941, he volunteered to serve in the Philippines. Upon receiving the news of the Japanese attack, the ship carrying James, his flight companions, and a group of 2,000 soldiers from the 131st Field Artillery, set course for Suva (Fiji Islands) and from there to Brisbane, Australia. Among the evacuees from the Philippines were the pilots of Basque origin Felix Larronde (not related to James) and Mitchell Cobeaga. Felix was born in Bishop, California, in 1922, to a Lapurdian father and a Californian mother, while Cobeaga was born in Lovelock, Nevada, to Bizkaian parents, in 1917. Many of their companions didn’t share in the luck of these pilots. The 27th ground personnel were not evacuated and became the 2nd Battalion of the Provisional Infantry Regiment (Air Corps), which was forced to fight as a regular infantry regiment, the first in the history of the United States Air Forces. Made up of some 900 soldiers, they fought against the Japanese for more than three months, finally being captured and sent to the fields in the so-called Bataan Death March, during which the Japanese committed endless atrocities. Half of them died. Similarly, the ground personnel of the 19th joined the infantry that would fight in the Bataan Peninsula, as was the case with another Basque in the unit, Paul Indart. Trained in the maintenance of the “Flying Fortresses,” Indart volunteered to serve in the Philippines, first at Clark Air Base which destroyed by the Japanese – Indart was unharmed – and then at Del Monte base in Mindanao. Indart was born in Reno, Nevada in 1916, to a father from Nafarroa and a Bearnaise mother.

As a consequence of the destruction of the US air bases in Clark (Pampanga) and Iba (Zambales) in central Luzon, the American fleet, left without air cover and for its own safety, was in turn evacuated to Java on December 12, although successive battles against the Japanese imperial army caused the loss of a large part of the American ships by February 1942. On December 27, 1941, Louis Erreca – born in 1905 in San Luis Rey, California, of a father from Nafarroa Beherea and a Californian mother – lost his life during a bombing mission from Ambon (Indonesia) against the Jolo Islands, in the Philippines. Six PBY Catalina seaplanes participated; only two returned. Erreca’s plane was the first to be shot down. He was the Aviation’s Chief Machinist’s Mate [ACMM] “Plane Captain.” His body was never recovered. As a result of his death, his son Louis Michael Erreca volunteered for the Navy when he was only 17 years old, participating two years later in the Battle of Leyte Gulf that would begin the Allied liberation of the Philippines.

The Japanese aerial bombardments were followed by the landing of troops in the north and south of Manila. The situation of General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the US and Philippine armed forces, was precarious: no aircraft, no naval force, and no reinforcements in sight, nor any supplies for a long resistance. The defending forces withdrew to the Bataán Peninsula, west of Manila Bay, and Corregidor Island, in the southwestern part of Luzon, with the goal of defending the entrance to the bay. Despite the declaration of Manila as an open city on December 26, 1941, to avoid its destruction, the fight continued in Bataán, Corregidor and Leyte, in the Visayas, until its final surrender. On December 24, the president of the Philippine Commonwealth, Manuel Luis Quezón, and his vice president Sergio Osmeña had been transferred from Manila to Corregidor.

“What happened in Bataán and Corregidor was a hell of fire and shrapnel. When it wasn’t artillery, the planes came to drop more and more bombs at us,” Arruza recalled. “When the Japanese occupied almost all of Luzon, they smashed us hard with their artillery.” Assigned to the Quezon and MacArthur headquarters in Corregidor, he continued his account: “To keep morale high, setting an example of incredible coolness, there was always MacArthur with his characteristic pipe. He was the ultimate symbol of resistance against the invader. To me, he was like a god of war. I never saw him stoop or throw himself to the ground, as others did to take cover from the shrapnel.”

Faced with the inevitability of military defeat, Quezón, Osmeña, their families, and members of the government were evacuated on the recommendation of the American government in February 1942, although they did so in separate transports (Quezón by submarine and Osmeña by boat). They were transferred to Melbourne, Australia, and from there to Washington D.C., where they established the seat of government in exile. Assigned to the aid group of President Quezón, Arruza was evacuated with Osmeña’s group to Iloílo, while the vice president and his entourage continued their journey into exile. “Thanks to this politician, I got rid of the terrible death march of the survivors of Corregidor [some 13,000] towards the Japanese concentration camps and all the penalties, which lasted until the end of the conflict,” concluded Arruza. At the request of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, MacArthur, his family and staff left Corregidor on March 11, 1942 for Australia, a scene we saw in John Ford‘s unforgettable film They Were Expendable (1945). Upon his arrival, MacArthur was appointed Commander of the Southwest Pacific Theater. General Jonathan M. Wainwright took command of the armed forces in the Philippines.

Bataán fell on April 9, 1942 and Corregidor on May 6. Wainwright surrendered unconditionally with the capture of Corregidor by the Japanese, although the last American troops surrendered in Mindanao on May 12. Wainwright was taken prisoner of war and became the highest ranking American soldier imprisoned by Japan. He was sent to the Formosa (Taiwan) concentration camp and later to Liaoyuan, China, until his liberation in August 1945 by the Red Army.

After the surrender of the US and Philippine troops in the Bataán and Corregidor Peninsula, they were captured and taken prisoner; Indart was among them. The prisoners of war – about 64,000 Filipinos and some 12,000 Americans – began a foot march of between 90 and 112 kilometers, starting from the south of the peninsula to Camp O’Donnell, a military base in Capas, Tarlac, on the same island of Luzón that the Japanese used as a temporary concentration camp. It is estimated that between 5,600 and 18,000 Filipinos and between 500 and 650 Americans died as a result of summary executions, murders, malnutrition, disease, and the cruelty of their guardians during the long march, which would later be christened the “Death March of Bataán.” Japan had not ratified the Geneva Convention, also known as the 1929 Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War.

The situation did not improve at Camp O’Donnell. An estimated 20,000 Filipinos and 1,500 Americans perished in that camp from hunger, disease, and brutality by their captors. Prisoners perished at the rate of hundreds a day. Corporal Indart, despite having survived the “Death March,” passed away on May 9 at the age of 26 at Camp O’Donnell. Similarly, Lance Corporal Joseph Arrizabalaga died on May 19 at the age of 21. Arrizabalaga, born in Boise, Idaho, to Bizkaian parents, had been sent to Bizkaia to continue his education when the Civil War forced him to return to the United States. He was assigned to the Philippines, forming part of the 808th Company of the Military Police, which in the face of the Japanese invasion he joined the infantry in defense of the country.

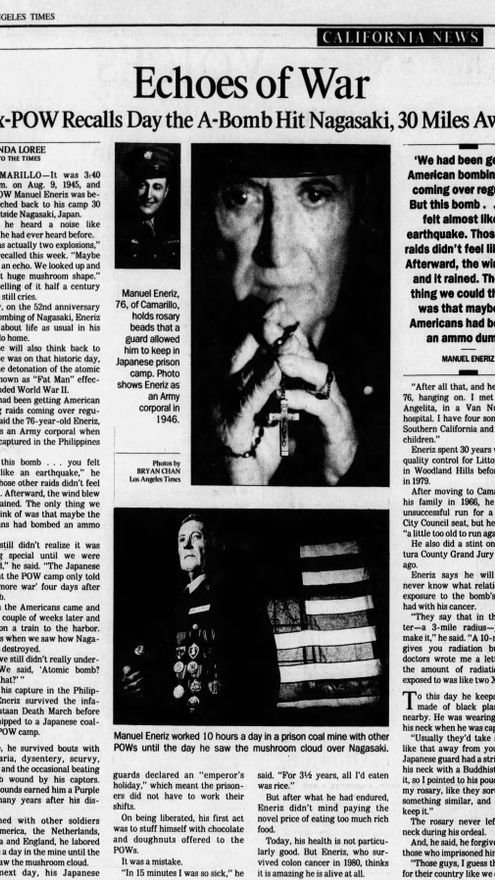

Manuel Eneriz was born in 1920 in Santa Clara, California, to a Nafarroan father and an Andalusian mother. Enlisted in March 1941, he was sent to the Philippines where he served with Company “K” of the 31st Infantry Regiment. Like most of the survivors of the Battle of the Philippines, Corporal Eneriz was taken prisoner and fortunately survived the infamous “Death March.” Although his situation was not serious enough, he was sent to the Fukuoka-Kashii prison camp, on the Japanese island of Kyushu, where he performed forced labor in a coal mine for ten hours a day for three years and six months until his liberation on the 15th of October, 1945, by American troops. He survived episodes of malaria, dysentery, scurvy, and occasional blows and stabbing by his captors. Those injuries earned him a Purple Heart many years after his discharge. During his captivity, at a distance of 30 miles from Nagasaki, he witnessed the atomic bomb hitting the city on August 9, 1945. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1997, Eneriz burst into tears as he recalled the event. He would dedicate his life to educating the youngest in the consequences of war and the high cost of freedom. “For me,” he used to emphasize, “every day is a Freedom Day.” He passed away in 2001 in Camarillo, California, one week after his 81st birthday.

General MacArthur, on his arrival in Australia at the small Terowie train station, standing before the journalists and the assembled crowd, sent a resounding and foreboding message to the Japanese invaders. “I’ll be back”. After their defeat and the end of US and Philippine control over the country, the Japanese occupation began, and a strong popular protest gave rise to an underground resistance movement and guerrillas. The Japanese Imperial Army organized a new puppet government known as the Second Republic, beginning in October 14, 1943, and led by President José P. Laurel. Dictator Francisco Franco congratulated the Japanese high command for its final victory and recognized Laurel’s collaborationist government. Later, he would change his mind, but that is another story.

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.