Begoña Echeverria

b.echeverria@ucr.edu

November 20, 2026

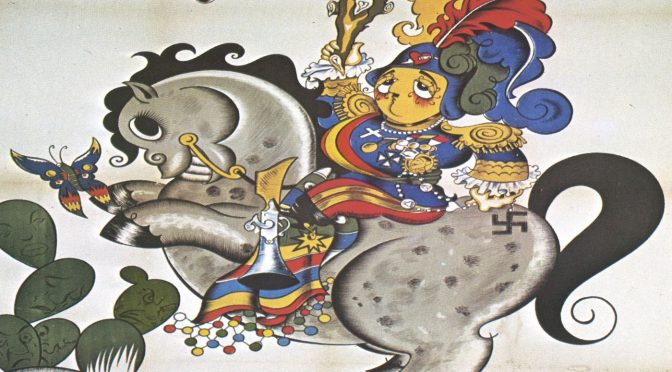

I first heard of Francisco Franco from Chevy Chase’s iconic sketch on “Saturday Night Live.” Riffing on repeated NBC news reports on the dictator’s supposedly imminent death for weeks before, “Weekend Update” host Chevy Chase announced Franco’s death, then quoted President Nixon praising Hitler as “a loyal friend and ally of the United States. He earned world-wide respect for Spain through firmness and fairness” – as a photograph of Franco grinning alongside Hitler is displayed. Watching the show on a little black-and-white TV in the kitchen with my mother, Pilarcho, I chuckled at the skit, as my mother held her fist in the air in triumph and scoffed.

That was 50 years ago. On November 20, 1975, dictator Francisco Franco—or El Caudillo por la Gracia de Dios, the Head of the Spanish State and the Head of the Government by the Grace of God, his preferred title—was finally dead. I recall no discussion of this momentous event with my mother after the skit was over. Ama did not elaborate on who Franco was, or why she was happy he was gone. And it would be decades before I would broach the subject again, not because I was afraid to or uninterested. It just never occurred to me. It was as if that gesture of defiance was all that my mother needed for closure. Perhaps that’s true. But when I did get curious about this dark chapter in Spanish and Basque history, when Franco ruled from 1939-1975, Ama didn’t have that much to say. No specifics, anyway. Maybe that’s not unusual. Like many immigrants, perhaps my mother had decided not to dwell on the more unsavory aspects of her country of origin. Or maybe Ama didn’t say much about Franco because his oppression didn’t impinge on her daily life. Possibly her life was not very different from that of her mother and grandmother before her, so there may not have been noticeable interruptions to her life experiences that she could attribute to the dictatorship. As a girl, she worked alongside her family on the baserri; as a young woman, she worked as a maid at a hotel/restaurant. Then she married my father, moved to America, and started a family. Never did she complain (at least to me) about the “traditional” strictures placed upon her.

The daughter of Basque immigrants to southern California, Begoña Echeverria is the Faculty Director of University Honors at UC Riverside and Associate Dean in the Division of Undergraduate Education. She has produced scholarly and creative works on Basque identity and culture. These include the monograph “Witches” and Wily Women: Saving Noka Through Basque Folklore and Song, the historical novels The Hammer of Witches and Apparitions, the play “Picasso Presents Gernika,” and four CDs with NOKA. With Annika Speer and Jacqueline Postajian, she is co-writer of the short film “Children of Guernica.”

And yet.

I wonder what Ama’s life would have been like had she not grown up during the Franco regime. For his triumph in the Spanish Civil War reversed policies of the short-lived Second Democratic Republic (1931-1936) that greatly expanded women’s rights. Alongside men, they were given the right to a free public education, the right to vote and the possibility of (civil) divorce for the first time. But the opportunities came to an abrupt end when Franco won the war on April 1, 1939. Rather than a democratic republic aspiring to expand the rights of women, “True Catholic Womanhood” reigned supreme. Women were extorted to focus on raising patriotic children for the Fatherland, to sublimate their own aspirations to support those of their men, and discouraged from pursuing university educations.[1]

Whether Ama ever felt the lack of prospects ushered in by Franco’s policies and politics, she did not let on. But I sometimes feel anger on her behalf – and on behalf of all the girls and women of Spain, in the Basque Country and beyond – for the freedoms and opportunities denied them by Franco and his minions. I channeled these feelings into lyrics I wrote for “Ama” in my play, “Picasso Presents Gernika.” As readers of this blog likely know, Franco allowed Hitler—with assistance from Mussolini—to bomb Gernika on April 26, 1937. It was the first aerial bombing of a civilian target, and understandably, parents sent their children abroad for safe-keeping: 20,000 in all.[2]

In the 1990s while living in Donostia, I met a British woman whose father had been among the 4,000 children evacuated to England, along with his brother. Eventually, their mother called for the brother to return to Spain, but not my friend’s father. He never learned why. Based on this story, in my play a mother sends her son and daughter to England after the bombing of Gernika. She eventually calls her son home, but leaves her daughter Andrea (“woman,” in Basque) in England, believing her daughter will have a better life under a democracy than a dictatorship. It is only at the end of the play that Andrea learns this. Below is an English version of lyrics I originally wrote in Basque.

1. He Let Them Bomb Gernika

Music and Fiddle: Belinda Thom

Lyrics & Vocals: Begoña Echeverria

Instruments, Production, & Mixing: Mario Verlangieri

He let them bomb Gernika

The bombs they killed my husband

I was left a poor widow

Me and my children

England sent El Habana

To sail our children away

I sent away my son and daughter

Will I ever see them again?

Oh, Blessed Mother

I leave my children in your arms

Protect them, and keep my children strong

Oh, Blessed Mother

Protect my children, keep them strong

Until they can come home

Franco killed our democracy

World War II began

England feared for its own children

And wanted to send ours back home

Franco took away our rights

Specially from girls and women

I called my son home, but left my daughter

Will you have a better life out there?

On February 20, 2022, “Picasso Presents Gernika” was staged at United Nations headquarters in New York City to commemorate World Refugee Day. It was the first and only time a live performance was staged in the venue, which can be viewed here: https://webtv.un.org/en/asset/k15/k15cv08mlb. Along with my co-writers Annika Speer and Jacqueline Postajian, I am working on a short film, “Children of Guernica,” which explores Andrea’s trauma and the healing she receives from her work as an art therapist for refugee children. (I invite you to consider making a tax-deductible donation toward the making of this film. Shooting begins in December and we hope to complete the film in 2026, funds permitting: https://creative-visions.networkforgood.com/projects/243481-children-of-guernica-s-fundraiser.)

Picasso famously proclaimed that he would not allow Guernica to be exhibited in Spain so long as Franco ruled as dictator. Almost as famously, he did not live long enough to see this happen: he died two years before Franco. But Picasso did experience Franco’s effrontery with regard to Guernica: In 1969, Franco called for the mural to be “returned” to Spain, as if the mural belonged to him.[3] Perhaps more insidiously, soon after allowing Gernika to be bombed, Franco falsely claimed that the Spanish Republican government – which included Communists and Basques – had destroyed Gernika. Franco’s war against truth soon turned to political violence against select groups of individuals. As suggested in “He Had Them Bomb Gernika,” Franco wasted no time in stripping women and girls of political rights they had briefly been bestowed during the Second Republic. But Franco’s political violence against women was particularly brutal. For decades, the Franco regime stole babies born to women he considered his political enemies – telling them their babies had died in childbirth – and gave the babies to his supporters. This was discovered when a reporter for the Spanish newspaper El Pais visited the grave of his sister, who – he had been told – had died decades before as a baby. He found the grave empty. (These and other violations of human rights committed by the Franco regime are investigated in the 2017 documentary, “The Silence of Others.”)

Franco never forgot that the Basque provinces of Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia allied with the democratic forces against him during the Spanish Civil War, and welcomed the chance to humiliate his Basque adversaries. On September 18, 1970, he presided over the Basque World championship for pilota in Donostia (San Sebastian), as if he had done nothing wrong. Incensed at Franco’s appearance at the Basques’ de facto national sport, Joseba Elosegi set himself on fire and threw himself from the second balcony, yelling “Gora Euskadi askatua!” (Long live a free Basque Country!). After seventeen days in a coma, Elosegi was sentenced to seven years in prison. (https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseba_Elósegui).

These instances, a few among so many, inspired the following song:

2. Francisco Franco You’re A Bad Bad Man

Lyrics & Vocals: Begoña Echeverria

Music based on “Death Don’t Have No Mercy In This Land” by Blind Gary Davis, adapted by Mario Verlangieri and Begoña Echeverria

Instruments, Production, & Mixing: Mario Verlangieri

Francisco Franco you a bad bad man

You said, “Hitler baby can I give ya a hand?”

You can try out your bombs on the Basque land

Francisco Franco you a bad bad man

Francisco Franco a conscience you lacked

You said was the Reds behind the attack

But hey, Pablo baby, gimme Guernica back

Francisco, a conscience you did lack

Francisco Franco took away our rights

Wrapping yourself up in Vatican white

You said baby girl, with you I got no fight

But, Francisco, you took away our rights

Francisco Franco you ain’t got no shame

You came just to watch a pilota game

I was so incensed, I set myself aflame

Francisco Franco ain’t you got no shame?

Francisco Franco: oh, the lies that you spread

I had me a baby, ya told me it was dead

But ya gave it away, so it wouldn’t be Red

Francisco Franco: oh, the lies that you spread

Francisco Franco, asto pitua zen

Conclusion

Writing and singing these songs has been a cathartic experience for me. Even though my mother rarely mentioned Franco or complained of the privations his policies imposed upon her, I take retroactive umbrage in her stead, as she is no longer with us. And rejoice that Francisco Franco is STILL dead.

Beharrik.

Works Cited

[1] Morcillo, Aurora. True Catholic Motherhood: Gender Ideology in Franco’s Spain. Northern Illinois University Press: Dekalb, 2000.

[2] Legarreta, Dorothy. The Guernica Generation: Basque Refugee Children of the Spanish Civil War. University of Nevada Press: Reno, 1984.

[3] “Franco Favors the Return Of Picasso and ‘Guernica.’” New York Times. October 28, 1969.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Oroitzapen tristeak, Blas

Presently, there is a movement in Spain of young people who admire the policies of Franco. Monique

Blas, this is an important post. I remember where I was when Franco died – eternal flames on his soul. I was in Gernika in 1968, watching the Guardia Civil strutting around with their machine guns. My Americanized mother gave them hell, much to the chagrin of my Aitxitxa.

Viscaya was like third-world country in those days, with Franco’s thumb on them all. After his death, it became an economically resurgent place. Euskadi is proudly spoken again.

Thanks.

Felip Barroetabena Holbrook

After Franco’s death Spain, including the Basque region, there was high inflation because of the global price of oil, high employment and political tension.

Many Basques immigrated to France, mostly around Bordeaux. Even during the time of Franco, the one who could escape, we took them in, hired them, and much more. I know that because my Dad was in the wine business and hired a Basque. Dad helped him to obtain his legal residency paper and later to sponsor him bring his wife and little girl from Spain. It was not a unique case. They were our neighbors in a bad situation. It was the decent thing to do.

When Franco died, Spain and the Basque region were rules by a king. It was not until the very late 1980s, when Spain joined the EEC European Economic Community . The economy of Spain was driven by foreign investment and export.

Last week, in the Wall Street Week program, the Chief executor of the bank of Santander, even though the bank is rich, she mentioned the decline of foreign investors.

Congrats to your Mom. Monique

Thank you for this post! The young speaking Euskara in the streets of Gasteiz, Donostia, Bermeo and Hendaia is the revenge of the Basque people. And the music!

True, but now the young people in Spain admire Franco. It is a revolving door of revenges every two or three decades since the period of Santxo Handia le Grand, the King of Navarre, 990-1035, when the kingdom of Navarre, meaning Basse Navarre on the French side were united.

Franco was brutal with the Basques. I suspect that he did not care about the music and the dances. In my opinion, he wanted what is inside the Pyrenees mountains: rare minerals.

In his book, Adam Hochschild, Spain in our Heart: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, wrote that the CEO of Texaco, sold fuel at a cheaper price to Franco.

Sabino Arana, also wanted revenge. He was responsible for many deaths on both side of the Basque region. Compare to Franco, Arana was a choir boy.

The Canfranc train station, once the pride of Franco–where he sends so many Jews to concentration camps is not a luxury hotel.

Monique