Over 100 years ago, in 1921, José Miguel de Barandiaran began publishing a series of articles under the banner of Eusko-Folklore. His work was interrupted by the Spanish Civil War but in 1954 he resumed publishing what he then called his third series of articles. These appeared in the journal Munibre, Natural Sciences Supplement of the Bulletin of the Royal Basque Society of Friends of the Country. While various writings of Barandiaran have been translated to English, I don’t believe these articles have. As I find this topic so fascinating, I have decided to translate them to English (with the help of Google Translate). The original version of this article can be found here.

More appearances of Mari

IN AMEZQUETA

Our mother saw how Mari de Txindoki left. She lived in the mill when she was little. Once, some men brought a pile of sacks of corn to the mill on a cart, and our mother unloaded the sacks from the cart onto the men’s shoulders. And, while the men were returning, as she was waiting for them, at night, she saw something burning and flaming coming out of the Txindoki chasm and disappearing [going] toward San Miguel. Our mother was frightened. Later, when the men had returned, she told them that she had seen something burning and flaming heading toward San Miguel [de Aralar]. They then replied that it was undoubtedly Mari. In the chasm where she [Mari] entered, everything was scorched.

(Reported in 1930 by Ignacio Altuna, from Amézqueta.)

IN BIDARRAY

The story of the apparition of Arpeko-Saindua (the saint of the cave) on Bidarray Mountain is similar to those recorded in previous legends about Mari. The themes of the blast of fire that enters a cave at night, the young woman who mysteriously disappears, the threatening voices of the night, and the curse and punishment of those who desecrated the cave all converge here, as in other stories about Mari.

On November 14, 1938, I visited the cave of Arpeko Saindua, accompanied by my friend Don Gelasio Arámburu and the Jatxou children’s colony.

We arrived at Bidarray station early in the morning. We crossed the Nive over the bridge called Onddoene’ko zubi (Onddoene Bridge). It is said that this bridge was built in one night by the legendary spirits whose name is lamin. We took a path to the right that climbs alongside the Bastan-erreka stream. We pass close to Arranteia (the swimming pool). Further on, we cross the stream in a narrow ravine over the Inpernuko-zubi (Hell’s Bridge), and continue along the path to cross the stream again higher up and take the path that climbs to the Arrusia baserri located on

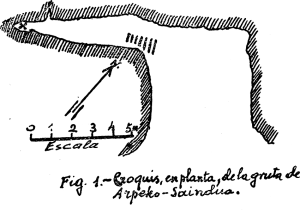

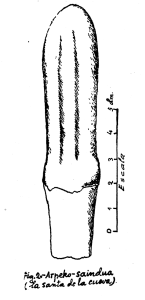

the southern slope of Mount Zelharburu. Still traveling uphill for 300 meters, heading west-northwest, we reach the Arpeko Saindua cave. Its entrance faces east-southeast. It is open in the banks of pudding stone and sandstone that form the southern escarpments of Mount Zelharburu. It has a vestibule 5 m wide, 5 m deep, and 6 m high. To the left, a meter and a half above the floor of the vestibule, there is a narrow gallery that is accessed by ten stone steps (fig. 1). It is a humid place: water drips from the ceiling. At the end of the gallery (fig. 1, x), there is a stalagmite column that reaches the ceiling: it measures 1.10 m in height and 0.20 m in average width. It resembles a human torso (fig. 2). A little water runs across its surface. This is the supposed saint of the cave. The etxekoandre, or lady of the Arrusia baserri, named Margarita Ibarrola, tells me the following:

A young girl got lost on Mount Euzkei [Iuskai, Iuskadi]. They only found her head. From then on, at night, for many years, voices were heard. “Wait! Wait!” someone shouted from the side of Mount Euzkei.

On one occasion, at midnight, they saw a light enter Zelharburu’s cave. Others said they had seen twelve lights. The surrounding villagers went to the cave and there saw the statue of the saint. From then on, the voices were not heard.

In front of the stalagmite column, there are candlesticks resting on rock outcrops. In them, devotees place the candles they offer to the “saint” and rub their bodies or sick limbs with the water that runs down the supposedly petrified “saint.”

She is invoked in cases of skin and eye diseases. Those who suffer from eczema (negal in Basque) are the ones who have particular devotion to the “saint” of this grotto.

While still inside the cave, we saw three women arrive from the Itxassou side with two girls. One of them, a young girl, lit a wax candle, traced a cross in the air with it in front of the stalagmite, and left it at its foot to be consumed there.

I returned to Zelharburu on April 20, 1945, and saw that the cult of the saint of the cave continued as before.

On the walls of the cave are many votive offerings: rosaries, crosses, medals, combs, handkerchiefs, shirts, and berets that the sick leave, believing that the illness that afflicted them remains in these garments. There is also a collection box where devotees deposit alms (cash and paper money). Since the collection box is broken, anyone can steal the money deposited there: many 10- and 20-franc bills can be seen. In the hollow beyond the stalagmite, we saw several bronze coins from the last century: some French and some Spanish. They were undoubtedly thrown there not to cover the expenses incurred by the care of that “sanctuary,” but for the supposed “saint” venerated there, and only for her. The almost inaccessible nature of the place where they were thrown shows that their donors did not want those coins to fall into human hands.

Both the devout pilgrims of Itxassou and one of the shepherds from the region named Antonio Intxaurgarate told me that, on one occasion, the owners of Arrusia closed the cave and began charging an entrance fee to those who came to visit the “saint.” Soon, all of the sheep of Arrusia fell into disgrace, tumbling down the rocks. The family of Arrusia then realized that this was a punishment sent by Arpeko Saindua and reopened the cave.

A pilgrimage is held here annually on Trinity Day, consisting mainly of dancing. Groups of young people of both sexes from the surrounding neighborhoods and villages attend.

There are procedures to attract Mari, and there are also those to remove her.

If she is invoked three times in a row, saying: Aketegiko Damea! “The Lady of Aketegi!”, Mari then appears and she sits herself on the head of the person who invoked her. This is the information we gathered from a report from Cegama.

But there are also means, mainly of a religious and magical nature, to which the power of preventing any action by Mari is attributed.

We have already recorded some cases of this kind on various occasions. Now I will simply transcribe the brief report that a resident of Mañaria sent me in 1930. It reads somewhat literary:

One afternoon, three or four of us were going for a walk, spending time in the mountains, taking time in the shade of a tree, and were talking and resting beside a stream. Suddenly, an old shepherd appeared and also rested beside us.

We talked with the old man for a long time and talked about many things, and finally, we recalled the storms that had raged here and there during this summer, etc. We talked about the weather in so many ways, each of us offering his own opinion. At this point, the old shepherd stood up and, thoughtfully, looked at us to tell us something important about the weather. Then he began to explain very seriously the cause of the storms. “Look! If the Lady of Amboto is inside the cave on Saint Barbara’s day, the following summer will be calm and abundant [in crops, etc.]; but if on that day she is outside the cave, the following summer there will be terrible storms and upheavals. And on Saint Barbara’s day last year, that Lady of Amboto walked in fire and flames along the Mugarra (1) side, and that is why all the storms, tempests, and evils this year are here.”

(1) Mugarra is a mountain located above Mañaria.

SUMMARY OF THE MYTHOLOGY OF MARI

Taking a look at what we have published so far about Mari, both in EUSKO-FOLKLORE and in “Mari o el genio de las montañas” (in Homage to D. Carmelo de Echegaray, San Sebastián, 1923), in “Die prähistorischen Höhlen in der baskischen Mythologie” (in Paideuma, Leipzig, 1941), and in “Contribución al estudio de la mitología vasca” (in Homage to Fritz Krüger, Mendoza, 1952), we could briefly summarize the main features of the conceptual and mythological world formed around this legendary name or divinity.

Names

Mari is the most general, alone or associated with the place where the numen resides:

- Basoko Mari’e (the Mari of the forest) as she is called in Urdiain.

- Aldureko Mari in Gorriti.

- Puyako Maya (Maya de Puya) in Oyarzun.

- Mari Munduko (Mari de Mundu or Muru) in Ataun.

- Marie Labako (Mari of the oven) in Ispaster.

- Mari Muruko (Mari de Muru or Buru) in Elduayen.

- Mari-mur in Leiza (according to my informant José Joaquín Sagastibeltza). Mamur is the generic name of certain beings who, according to beliefs of the Vera region, appear at night in the form of monsters.

- Marije kobako (the Mari of the cave) in Marquina.

- Mariarroka in Olazagutía.

- Mariurraka in Abadiano.

- Mariburrika in Garay and Berriz.

- Andre Mari Munoko (Lady Mari de Muno) in Oyarzun.

- Andre Mari Muiroko (Lady Mari de Muguiro) in Arano.

- Muruko Damea (the lady of Muru) in Ataun.

- Aralarko Damea (the lady of Aralar) in Amézqueta.

- Putterriko Damea (the lady of Putterri) in Arbizu.

- Illunbetagaineko Duma (lady of Illumbetagaina) in Lakunza.

- Beraingo lezeko Dama (Lady of the Cave of Berain) in Lakunza.

- Aketegiko Damea (the lady of Aketegi) in Cegama.

- Anbotoko Dama (lady of Amboto) in Zarauz.

- Amuteko Damie (the lady of Amute) in Azcoitia.

- Arrobibeltzeko Andra (Lady of Arrobibeltz) in Ascain.

- Anbotoko Señora (Lady of Amboto) in Aya, in Arechavaleta and in many other towns in Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya.

- Anbotoko Sorgiña (the witch of Amboto) in Durango.

- Aketegiko Sorgiñe (the witch of Aketegi) in Cegama.

- Arpeko Saindua (the saint of the cave) in Bidarray and other towns in Navarre and Laburdi.

- Gaiztoa (the evil one) in Oñate.

- Sugaarra (the snake) in Ataun.

- Yona-gorri (she of the red skirt) in Lescun.

- Lady and Sorceress in the “Livro dos Linhagens” by Count Don Pedro (16th century).

The name Mari may have some connection with the names Mairi, Maide, and Maindi used to designate other legendary figures in Basque mythology, although the themes associated with these are different. The Mairi are the builders of dolmens; the Maide are male spirits of the mountains, while their female counterparts are the Lamin, or spirits of springs and rivers; the Maindi are perhaps the souls of ancestors who visit their former homes at night, according to beliefs in the Mendive region.

The name Maya undoubtedly has a connection with Maju, who is considered to be Mari’s husband and must be the same name that Lope Garcia de Salazar called Culebro, father of Jaun Zuria, and in Ataun they call Sugaar “snake” and in Dima Sugoi “snake.”

Forms of Mari

Legends attribute Mari to the female sex, as they do to most of the deities featured in Basque mythology.

Mari often appears in the form of an elegantly dressed lady, as we are told in the legends of Durango, in which she also appears holding a golden palace in her hands. She is similarly represented in the stories of Elosua, Bedoña, Azpeitia, Cegama, Rentería, Ascain, and Lescun. In the latter town, she wears a red skirt.

- According to data collected in Amézqueta, during storms she appears in the form of a lady seated in a chariot crossing the air pulled by four horses.

- She has been seen in Zaldivia in the form of a woman breathing flames.

- A woman wrapped in fire, lying horizontally in the air, crosses space, as described in a legend from Bedoña.

- A figure of a woman breathing fire, sometimes dragging a broom and sometimes chains, depending on the noise that accompanies her, so they say in Régil.

- A lady riding a ram, according to legends from Oñate and Cegama.

- A large woman whose head is surrounded by the full moon, according to what was seen in Azcoitia.

- A woman with bird feet, they say in Garagarza.

- A woman with goat feet, according to the “Livro dos Linhagens” by Count Don Pedro.

- She appears in the form of a goat in Auza (Baztán Mountain).

- She appears in the form of a horse, according to legends from Arano.

- She was seen in the form of a heifer, according to a story from Oñate.

- Many Cegamese have seen her in the form of a crow in the Aketegi cave.

- According to the beliefs of those in Orozco, she lives in the great cave of Supelaur in Itziñe, where she and her companions appear in great numbers in the form of vultures.

- In one legend from Oñate, she appears in the form of a tree, whose front part resembles a woman; in another, she is said to have appeared in the form of a tree that gave off flames from all sides.

- In Escoriaza, they say that the Lady of Amboto sometimes made herself known in the form of a gust of wind.

- She sometimes appears in the form of a white cloud, according to a legend from Durango. The same is also said in Ispaster.

- She has sometimes been seen in the form of a rainbow.

- In Oñate, Segura, and Orozco, they say they have seen her in the form of a ball of fire.

- She often takes the form of a fiery sickle, according to accounts from Ataun, Cegama, and Zuazo de Gamboa.

- In the Zelharburu grotto (Bidarray), she is seen petrified in the form of a human torso.

Despite the variety of forms in which legends present Mari, they all agree that she is a woman.

Mari generally takes on zoomorphic forms in her underground dwelling; other forms outside of it, on the surface of the earth, and when she crosses the firmament.

The animal figures such as bulls, rams, goats, horses, serpents, vultures, etc., that are mentioned in the legends concerning the underworld, therefore represent Mari and her subordinates, that is, the terrestrial spirits or telluric forces to whom people attribute the phenomena of the world. The cases of changes in form, mentioned in various stories, confirm this idea.

Mari’s Abodes

Mari’s ordinary abode is the regions beneath the earth. But these regions communicate with the earth’s surface through various channels, which are certain caverns and chasms. For this reason, Mari appears in such places more frequently than in others.

(To be continued)

José Miguel de Barandiaran

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.