This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario. You can find all of the English versions of the Fighting Basques series here.

Even more than the devastating attacks by German U-boats against the Allied merchant navy on the Atlantic coast, in the Gulf of Mexico, or in the Caribbean, or the failed espionage attempts by Abwehr military intelligence agents on US soil, the greatest military challenge during World War II (WWII) to the integrity of the United States came from Japan. Not only did Japan cause the United States to enter the armed conflict with the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, but it also brought the tragedy of the war to the Aleutian Islands of the Alaska Territory (in American hands since 1867) six months later, symbolically putting American society “in check.”

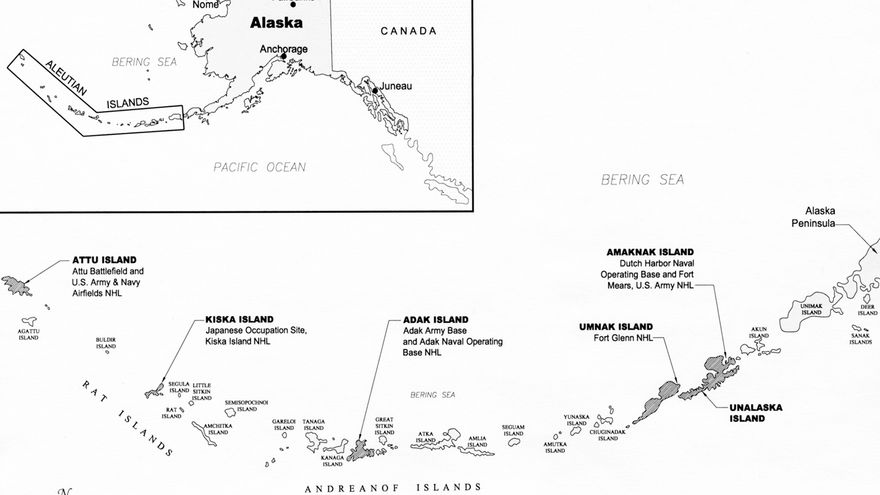

The Aleutian Islands are a chain of volcanic islands with a length of 1,900 kilometers (1,180 miles) between the Bering Sea and the northern Pacific Ocean that extend between the peninsulas of Alaska and Kamchatka, in Russia. Characterized by a hostile climate and inhospitable terrain – with high mountains and thick tundra – they were inhabited by a few thousand people of the Unangan ethnic group (also known as Aleutians). Sadly, they became unwitting witnesses to the atrocities of a war on an isolated front whose strategic value is still questioned today. Was the Japanese invasion of the Aleutians a diversion from the attempt to storm Midway Atoll in the central Pacific? Or was it an attempt to protect the northern flank of its military expansionism? Or was it the beginning of a potential air assault on the west coast of North America?

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

On June 3, 1942, the Japanese Imperial Navy launched a first air attack against the naval base and Fort Mears of the US Army in the city of Unalaska, in Dutch Harbor (Amaknak Island, the most populated of the Aleutians). They would repeat the attack on the 4th, coinciding with the beginning of the naval Battle of Midway (June 4-7, 1942), whose objective was to widen the defensive perimeter of Japan. The airstrikes on Dutch Harbor – the first in history against the American mainland – claimed the lives of about forty Americans. This pyrrhic victory paled before the American victory at Midway and from whose defeat the Japanese navy would not recover, since it prevented not only the final blow to the American fleet, but ensured the impossibility of their own fleet exercising dominion over the entire Pacific. On the 6th, 600 Japanese marines invaded Kiska Island, completely uninhabited except for 12 researchers from the US Department of Aerology. This was the first time that an American territory fell into foreign hands since its independence, which was a severe blow to American morale, increasing panic among the civilian population of the west coast due to the fear of air attacks. Throughout its occupation, the Japanese detachment had more than 5,000 soldiers who strove to build all kinds of defensive infrastructure, reaching the highest proportion of antiaircraft batteries of any other enclave in the Pacific. On the 7th, some 1,100 Japanese infantrymen stormed Attu Island, the furthest from the Alaskan mainland (about 1,800 km away) and which was populated by about fifty Unangans. After three months, some 47 survivors were taken as prisoners to the port city of Otaru, on the island of Hokkaido, in Japan, of whom almost half died of starvation. (After their release in 1945, they never returned to Attu.) Faced with an escalation of invasions and a scorched earth policy (infrastructure, houses and churches were burned), the American authorities ordered the forced evacuation of about 900 Unangans (about 500 from the islands of Atka, on June 12, and from Saint Paul and Saint George, on the 14th) to southeast Alaska where they were held in internment camps in inhumane conditions for another two years (1).

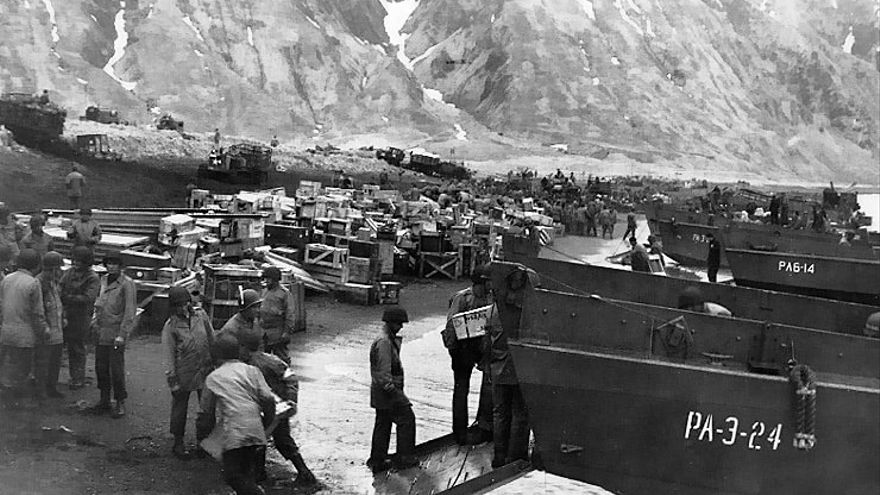

On August 7, 1942, the United States began Operation Watchtower, giving rise to the Battle of Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands, and the victory of which marked the beginning of the great allied offensive in the Pacific. In its shadow, on August 30, the United States launched a counteroffensive to recover the two Aleutian islands from Japanese hands, which reached 144,000 American and Canadian soldiers against a Japanese force of about 8,500 Japanese, of whom more than half perished. Military operations in the Aleutians became a true combat laboratory, where the tactics developed would be employed throughout the Pacific campaign. Among the US contingent we have been able to identify a good number of soldiers of Basque origin. The first Allied objective was to secure the Island of Adak, in which the submarine USS S-33 (S-138) took part. Among the crew we find the veteran Chief Electrical Officer Joseph Peter Tabar, of Navarrese origin, who had been born in 1904 in Los Angeles, California. Of the eight patrols the submarine carried out during the war, six were carried out in the Aleutians from July to December 1942, including protecting the convoy that occupied Adak (400 kilometers from Kiska and about 720 kilometers from Attu). After the island was secured by some 4,500 US military personnel, an air base was established – with an airport built in record time – in which Sergeant Gene Acaiturri of the 515th Combat Engineer Company quite possibly participated. Acaiturri was born in Mountain Home, Idaho, in 1919 to Biscayan parents. The ultimate goal was to bombard the Japanese positions at Kiska and Attu. The bombing campaign was carried out both from Adak and Amchitka (occupied by American troops on January 12, 1943; at a distance of 117 kilometers from Kiska and about 445 kilometers from Attu) in the summer and fall of 1942 and throughout much of 1943.

The Basque-American aviation support equipment technician Floyd “Ike” Cortabitarte, born in Jordan Valley, Oregon, in 1917, was aboard the USS Louisville in the Aleutians when Japan launched the attack in June 1942. At the same time, aboard the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis was sailing Assistant Electrician First Class Anthony Lizoain. Lizoain was born in 1911 in Santa Barbara, California. During 1942, both the Louisville and Indianapolis escorted convoys and bombed Japanese ships and facilities in Kiska Bay.

The US Navy imposed an iron blockade on the islands of Attu and Kiska in order to prevent them from being resupplied. In February 1943, the USS Indianapolis intercepted a Japanese cargo ship, loaded with troops, ammunition, and supplies, destined for the bases on Attu and Kiska. On March 26, a Japanese supply transport convoy, escorted by several destroyers, was intercepted near the Russian Komandorski Islands, with the light cruiser USS Richmond taking part. On board was engineer assistant Michael Errecart. Errecart was born to a Laburdine father and a Navarrese mother in 1919, in the Californian county of Fresno. After an intense battle, the Japanese fleet was forced to give up its objective. From then on, the Attu and Kiska bases only received supplies sporadically from submarines.

The cruisers USS Louisville, Indianapolis, and Richmond, joined by the battleship USS Idaho, among others, provided covering fire to amphibious assaults, both at Attu and later at Kiska. An old acquaintance was traveling on the Idaho, the Basque-Californian Ralph Irigoyen – Artillery Assistant First Class – who, like many of his companions that served in the Aleutians, would continue his journey throughout the Pacific. Irigoyen participated in the D-Day of the Pacific Theater with the invasion of Saipan.

On May 11, 1943, 77 years ago, some 12,000 American soldiers, mainly from the 7th Infantry Division, began the invasion of Attu Island. It was the first US offensive in the Pacific, two months before the famous Guadalcanal landing. The soldiers, without specialized training or adequate equipment for the harsh climate, without sufficient provisions and with great difficulty in maneuvering their vehicles on the tundra, also had to face a motivated, acclimatized enemy with perfect knowledge of the island.

In the invasion of Attu we find several Basque-Americans, for example, Captain Leon Etchemendy (born in Gardnerville, Nevada, in 1918) and Sergeant Matthew Etcheverry (Fresno, California, 1916). Both would be seriously injured during the campaign to liberate the Philippines. Serving in the 184th National Guard Combat Regiment were Corporal Donald Urain (Marysville, California, 1922) and Sergeant Joseph Urriolabeitia (Boise, Idaho, 1919). The 184th was the only National Guard regiment that participated in the recovery of American soil lost to a foreign enemy during WWII. Urriolabeitia was also wounded in Leyte, Philippines, and was killed in Okinawa at age 25. He received a bronze star and a purple heart. We also have another Basque-Californian, Sergeant John Errea Etchenique, born in 1918 in Bakersfield.

After 18 days of small-scale attacks and ambushes by Japanese snipers, the balance turned to the American side. Desperation prompted the surviving Japanese, led by their colonel, Yasuyo Yamasaki, to launch a suicide charge, banzai, against the US positions on May 29. It was one of the largest suicide attacks to occur at the Pacific Theater. An estimated 1,400 Japanese soldiers lost their lives in just a few hours. Only 28 men survived. The island was returned to American hands at a cost of 549 Americans killed and about 3,300 wounded (most as a result of extreme cold, illness, accidents and psychotic crises) and 2,351 Japanese killed, almost 100% of the enemy troops. Despite being one of the most unknown battles today, the Battle of Attu became one of the bloodiest in the Pacific, second only to Iwo Jima. After Attu was liberated, on August 15, 1943, approximately 35,000 US and Canadian troops landed at Kiska. They expected the worst. However, to their surprise, the Japanese troops, some 5,200 soldiers, had left the island two weeks earlier. The Aleutian Campaign was ending.

The military operation in the Aleutian Islands will be remembered for being a year-long campaign fought amidst snow, frozen mud, thick fog, freezing temperatures, constant rains, and intense gusts of wind; a place whose waters were and continue to be considered some of the coldest and stormiest of the world. The lives of American soldiers were perfectly reflected in a short war propaganda documentary, “Report from the Auletians,” shot by John Huston in 1943, in which the silence and monotony that made such a dent the morale of the troops could be felt (2). The landings at Attu and Kiska were the only invasions the US suffered during WWII, while the offensive for the liberation of Attu was the first land battle fought on US soil since the War of 1812. For the Unangans, life was never again the same. Many were unable to return home to rebuild their lives. The US government did not provide them with the means to rebuild their towns, nor did it compensate them in any way for their internment or for the material losses suffered during their forced evacuation. The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 (and its 1993 extension) was an attempt by Congress to compensate survivors. Seventy-five years later, in 2017, the US government formally apologized for the internment of the Unangan people and their appalling treatment during captivity.

(1) Chandonnet, Fern. (2007). Alaska at War, 1941-1945: The Forgotten War Remembered. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press.

(2) Huston, John. (1943). Report from the Auletians. US Signals Corps.

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of Two Wars,” send us an original article on any aspect of the WWII or the Spanish Civil War and the Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Basque Combatants in World War II”.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m looking for information about Basque escapees from the Spanish Civil war who may have gone to Alaska to work for a young adult novel I’m writing. Really appreciate any help you can give. Thanks. Val

Hi Val, I’m not sure how to figure out something like that. One resource to try would be the Basque Museum in Boise. They may have some info or leads they could point you to. But, I’m not sure how else you would find that kind of information.