This article originally appeared in its Spanish form in El Diario.

War was inevitable. The United States – despite its “neutrality” and even without considering the huge supply of raw materials and war machinery it would send to the United Kingdom in the near future – was the only country capable of standing in the way of Japan’s expansionist wishes. In February 1940, in a gesture that did not go unnoticed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the transfer of the entire Pacific military fleet from their naval bases in California to the Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, a movement that was seen by Japan as a serious and potential threat to its interests.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

Japan aspired to be the leader of a new political order in Asia at the cost of seizing the British, French, Dutch, and American colonial territories, and thus extending, without hindrance, its influence in the rest of Southeast Asia. And as such it was recognized by the western powers of Germany and Italy through the Tripartite Pact of September 27, 1940. Previously, after the fall of France into the hands of Nazi Germany, Japan had invaded French Indochina (Vietnam) on September 22, 1940. As a reaction, the US suspended all exports to Japan, including oil, which accounted for 80% of the total obtained by the country of the Rising Sun. The situation was critical and the only solution was to neutralize the US on its way to the Dutch East Indies, which held significant oil reserves that could feed its insatiable war economy.

Some thirty ships, including six aircraft carriers with 420 aircraft on board, and 16,000 men from the Imperial Navy of Japan, crossed about 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) of the Pacific Ocean, undetected, with the aim of ending the meddling of the United States with a preventative attack that would theoretically mean the end of its fleet on the West Coast [1].

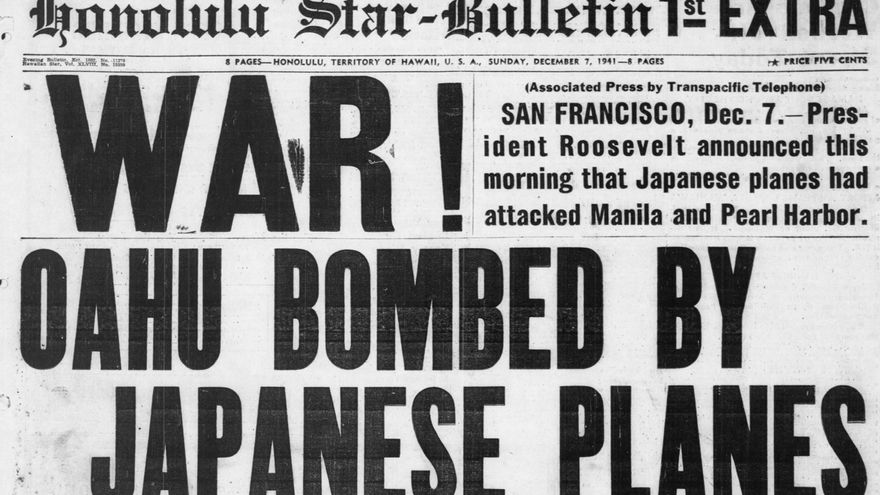

Without warning, on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, Japan launched 353 aircraft from its carriers in two waves of attacks. These air raids were supported by two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, two battleships, eleven destroyers, and 35 submarines. Within just a few hours, Wake Island, in the US, was in turn also razed. On Wake Island, there were seven Basque-American workers, hired by the Morrison-Knudsen engineering company of Boise, Idaho, who were paradoxically building military defenses against a possible Japanese attack.

The American defenses of Pearl Harbor, taken by surprise, offered little resistance to the incessant aerial bombardments. Barring extraordinary instances of heroism, American military and civilians were stunned bystanders of the chaos and catastrophe unleashed by the Japanese. Their placid lives had turned into a nightmare. They had unwittingly become historical witnesses to the unwanted involvement of the United States in the Second World War (WWII). Among them we have been able to identify six people of Basque origin who experienced it first hand. They are Mary Sala, the brothers Fermín and Alfonso Aldecoa Arriandiaga, Leandro Urcelay Llantada, Gregorio “George” Ascuena Monasterio, and Domingo Amuchastegui Guenaga.

Mary Sala, born in 1920 in Ely, Nevada, to a Nafarroan father and a Quebecer mother, who died when Mary was 6 months old. Unfortunately her father died in 1928, leaving her and her older brother, John, orphans at only 8 and 10 years old. Without a relative, the authorities decided to send them to an orphanage in Ogden, Utah. Fortunately, a neighbor in Ely, the Behe Nafarroan Catherine Mong Bercetche, married at the time to another Behe Nafarroan Louis Harriett (they will later separate), decided to adopt them and raise them together with her other two children, Emile Josephine and Louis Genty “Shanty.” It would be at the University of Nevada, in Reno, from where she will later graduate, where Mary met her future husband Mitchell Anton Cobeaga Laca, born in 1917 in Lovelock, Nevada, to Bizkaia parents. Mitchell, commissioned as a lieutenant in the Air Force in May 1940, married Mary in April 1941, was destined for a post at the Hickam Air Force Base, Honolulu, on the island of Oahu, as a pilot of the 19th Bombardment Group, assigned to the mythical Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress.” At that time, the command decided to transfer the group to the Philippines to improve its air defense in the Pacific, a move in which Mitchell participated. He was on a transfer flight to the US when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The Hickam base was completely devastated, killing 189 people. Young Mary, four months pregnant and from her home in the port, was a privileged witness of how Japanese aviation attacked the North American fleet; the ship bearing the name of her home state – the USS Nevada – was the only battleship to get underway that day, although it was hit by a torpedo and no fewer than six bombs, eventually sinking in the port.

Her brothers John and Shanty later served in the Navy in the Pacific Theater of Operations during the war. Her husband Mitchell continued his military career until his retirement in 1968 with the rank of colonel, having also participated in the Pacific front during WWII, and later in Korea and Vietnam. Mary passed away at the age of 76 in Las Vegas, Nevada.

The brothers Fermín and Alfonso Aldecoa, born in Boise in 1915 and 1918 to Bizkaian parents, were in Honolulu working for the aforementioned Morrison-Knudsen company in its main office in Pearl Harbor doing accounting work. Morrison-Knudsen had been contracted by the US government to develop different naval military projects, including at Pearl Harbor, Midway, and Wake Island. Fermín, 26, had arrived in Honolulu from San Francisco, California, aboard the SS Mariposa in September 1941, while his brother, 23, had arrived in April on the SS Lurline. Hawaii, an exotic and distant island in the Pacific, seemed to be the ideal place to take a job, with a salary that was almost double what they would receive in Boise. Their experiences would be unforgettable, but for a very different reason, as they witnessed the hecatomb caused by the Japanese attack.

After two years working at Pearl Harbor, the Aldecoas returned to Boise. Fermín retired as chief accountant at Morrison-Knudsen’s Boise headquarters after 39 years of service, passing away in 2006 in his hometown at the age of 91. Alfonso also retired from Morrison-Knudsen and died in Eagle, Idaho in 1995.

Leandro Urcelay was another witness to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Born in Barakaldo, Bizkaia in 1896, he had arrived at the Port of New York in 1919. He made Massachusetts his home, where he married an Azorean, having two children. A merchant marine by profession, and an excellent make of ship models, he had been recruited as an agent of the United States Secret Service and sent on his first mission to Pearl Harbor a few days before the tragic events. The nature of the enigmatic man from Barakaldo’s mission and his service to the US government is unknown. He passed away in Miami, Florida at the age of 82.

Lastly, we find the young recruits Gregorio Ascuena and Domingo Amuchastegui stationed on Oahu. They were born in 1918 in Gooding, Idaho, and in 1923 in McDermitt, Nevada, respectively, both of Bizkaian parents. Gregorio Ascuena was an inexperienced Marine who had only been in the Corps for a few months. He had enlisted in February 1941, being stationed at Marine Corps Air Station Ewa, seven miles west of Pearl Harbor. This airbase holds the sad record of having been the first military installation attacked during the aerial bombardment, having occurred two minutes before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Despite the desperate defense carried out by Gregorio and his companions with the weapons at their disposal, the 48 airplanes that were at the airfield were destroyed or disabled. The sailor Domingo Amuchastegui was also a newcomer. At just 18 years old, since November 25, 1941, he was part of the crew of the submarine support ship USS Pelias, docked in Pearl Harbor. During that fateful morning, the Pelias managed to successfully shoot down a Japanese torpedo plane and seriously damage another.

Domingo passed away at the age of 54 in Medford, Oregon, while Gregorio passed away at the age of 88 in Mountain Home, Nevada.

The attacks carried out during those two interminable hours concentrated their entire arsenal on the airfields and the cruise ships, captive in their own docks. 2,403 Americans were killed, including a hundred civilians, and about another 1,200 were wounded. The attacks destroyed 169 Army and Navy aircraft while another 159 were damaged, while only 19 ships were damaged, including eight of the battleships. Only one auxiliary ship and two battleships, the USS Oklahoma and Arizona, were totally destroyed. 1,177 men died aboard the Arizona, almost half of the total human losses. Japan lost 129 soldiers, 29 planes, and 5 small submarines.

The Japanese attack momentarily paralyzed the US fleet, facilitating Japan’s territorial expansion across the Pacific. Twenty-four hours later, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Wake Island, Guam and Midway, it was the Philippine archipelago’s turn. Japan soon had in its possession, among others, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Burma and the Netherlands East Indies, coveted for their precious natural rubber and petroleum. Thus, Japan broke the oil blockade imposed by the US since the end of 1940, and was able to replenish its needy civil and military industry. However, the American aircraft carriers were intact, while most of the damaged ships would be repaired between 1942 and 1944, progressively going into active service.

President Roosevelt requested an immediate declaration of war. On December 8, 1941, in his speech to Congress entitled “December 7, 1941 A Date Which Will Live in Infamy,” he called for a state of war to be declared between the United States and Japan. He was blunt :

YESTERDAY, December 7, 1941 a date which will live in infamy the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan. […] No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory. [2]

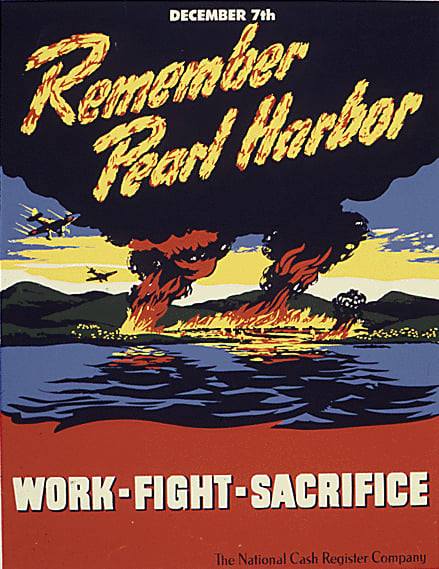

The slogan “Remember Pearl Harbor” would be followed by “America will never forget,” linked to the attack and subsequent invasion of Wake Island. On December 11, 1941, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. More than 16 million Americans – including hundreds of Basque origin – would join the Armed Forces during World War II. Pearl Harbor symbolized the dramatic awakening of a military giant, asleep until then.

The Basque survivors of Pearl Harbor – the Aldecoa and Urcelay brothers – were called up in 1943. The eldest of the Fermín brothers would serve as an investigator in the Army’s Counterintelligence Corps in the South Pacific. Alfonso served in the Air Forces in Europe as a radio operator aboard a B-24 bomber. Urcelay, 47, was assigned to the United States Naval Construction Battalions, the “Seabees.” Lastly, Amuchastegui continued to serve on various Navy ships throughout the Pacific, while Marine Aviatior Ascuena would fight in Luzon, Philippines; for his actions beyond duty he received the Silver Star. It is the beginning of the legacy of the “Fighting Basques.”

[1] Prange, Gordon W., 1910-1980, Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon (1981). At dawn we slept: The untold story of Pearl Harbor. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[2] Roosevelt, F. D. (1941). Speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York Transcript. Library of Congress.

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Basque Combatants in World War II”.

[1, 2, 3] Steve Ranson interview with Gary Parisena on April 18, 2019. “Final farewell for Nevada World War II veteran”. Lahontan Valley News for The State.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Fighting Basques: Six Basques at Pearl Harbor, The Day of Infamy”