“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario on December 25, 2019.

Discussion of the Basque participation in the Merchant Marines of the Allied countries and more specifically in the United States during the Second World War (WWII), despite some non trivial efforts, have certainly been tangential, perhaps due to the immense scope of the topic. Furthermore, these works, in general, have not treated these sailors and merchant marines as war combatants but as auxiliary elements, although certainly crucial in the war machine itself. Until not long ago, for example, studies on emigration spoke almost exclusively in a masculine key, discarding immigrant women and thus relegating them to a secondary and passive role of mere companion to the migrant man. In our research project, “Fighting Basques,” on WWII veterans of Basque and Navarrese origin, we not only include them as such but we also try to vindicate their key role in the face of public recognition for having been, although to a certain point of view understandable, made invisible by the role played by the different strictly military branches.

Of the dozens and dozens of war movies, few or none come to mind that focus exclusively on the merchant marine. To a certain extent, the public is largely unaware that without their participation in the war, allied troops, transported across the planet, would also have had enormous difficulties in obtaining the resources (weapons, fuel or food) they needed to continue fighting. Some 7 million soldiers and some 126 million tons of supplies were shipped from US ports during the course of the war. It took 15 tons of supplies to support a soldier for a year at the front. Possibly Action in the North Atlantic of 1943 is the most famous feature film of the time about the United States Merchant Marine (USMM) in WWII. Produced by Warner Bros., directed by Lloyd Bacon, and starring Humphrey Bogart and Raymond Massey, Action in the North Atlantic is a propagandist film about two merchant sailors, portrayed as patriotic heroes without uniforms, whose ship has been sunk by a German submarine and survive for several days adrift. But it was John Ford in The Long Voyage Home (1940) who – using great spotlights and shadows, according to his biographer J. McBride – was the first to show us the human drama and the fatality, not to mention longing, of those who went through life entrusting their fortune to their fellow crew members.

Perhaps it is pertinent to remember that the main means of transport at this time and during the war, due to the large volume of cargo, was naval. In the absence of complete and reliable statistics, all the sources consulted point to a high number of Basque sailors and mariners, many loyal to the Spanish Republic, serving not only under the Spanish flag, but also British or American. Some would collaborate, to varying degrees, with the Information Service of the Basque government in exile, particularly in South America, and others participated directly in the transport of troops and the supply of critical supplies to the Allies. Our investigation has not yet been completed and it would be very risky at this time to even venture an approximate figure on the number of people of Basque origin who sailed under the American flag between 1941 and 1945 due to the difficulty of identifying the crews of the hundreds of ships that formed part of the US Merchant Marine, mobilized in the service of the US government.

Nor would it be wrong to remember that the merchant crew were not military personnel but civilians and volunteers, who consciously or not assumed the same risks as the soldiers themselves who were part of the military proper. Both the navy and the army lacked cargo ships, so they had to rely on the merchant marine, which became an essential element for the war effort. The demand for crew members grew exponentially. It was not necessary to wait for the official entry of the US into the war, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (Hawaii) on December 7, 1941, to see the consequence of this on the merchant ships and their crews. It is estimated that at least 243 sailors perished as a result of enemy action by Germans and Japanese before December 7, while 160 were taken prisoner by the Imperial Japanese Navy, becoming the first American POWs of WWII. They were not only exposed to enemy planes, submarines and mines but also to nature itself in the form of hurricanes and storms in all kinds of latitudes and climates.

The German declaration of war on the US on December 11 exposed the USMM to the fearsome Nazi submarine fleet or “Unterseeboot” (U-boats), which caused real havoc mainly in 1942. Between February and May 1942, about 175 ships were sunk by U-boats along the North American East Coast, a time when the navy provided little or no military cover even though the USMM was under the control of the Armed Forces. Some 500 American merchant ships were sunk or damaged, with a loss of 4,300 sailors, throughout 1942. The situation from the summer of 1942 gradually changed. The Navy provided the USMM with members of the Armed Guard – a military force constituted by the Navy in October 1941 as an armed force aboard merchant ships – and artillery, and organized convoys escorted by destroyers and aircraft carriers to repel enemy attacks. These measures prevented the catastrophe that occurred at the beginning of the war from repeating itself.

The American Merchant Marine at War association estimates that between 215,000 and 285,000 men were part of the USMM during the war. After the end of the war, most of them rejoined civilian life, without public recognition, tributes or military honors, and certainly without benefits reserved exclusively for the military, including doctors to treat disabilities and lasting injuries. Few know that the crews only collected their pay while they were sailing. From the moment their boats were sunk, the sailors stopped receiving pay until the survivors re-embarked, if they were unharmed or not seriously injured.

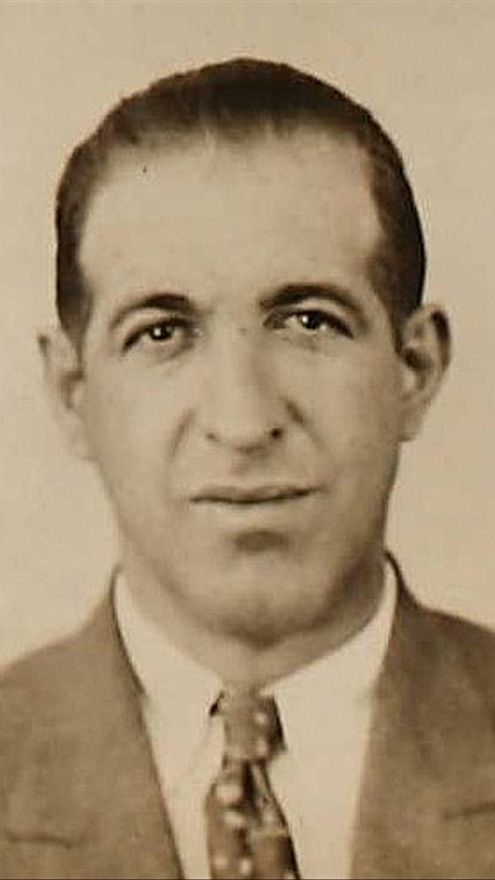

It is not surprising, therefore, that among the identified sailors of Basque origin, there are those who, despite having survived a German attack, returned to sail as if nothing had happened. This was the case of Antonio Uribe Echevarria – born in Busturia, Bizkaia, in 1886 and living in Brooklyn, New York. He was a fireman (also called a stoker or watertender in charge of the levels of refrigeration in and maintenance of the boilers) on the passenger ship SS Cherokee when on June 15, 1942, en route from New York to Boston, it was torpedoed twice and finally sunk by the submarine U-87 commanded by Joachim Berger (who would receive the Iron Cross First Class on July 2 1942). 65 members of the crew, 20 soldiers of the Army the ship was transporting, and a member of the Armed Guard died. Uribe and 82 other people survived the attack, being rescued by the merchant ship SS Norlago and the Coast Guard cutter Escanaba. However, his fate was cast. Uribe embarked on the SS Coamo, another passenger steamship (also used as a military transport ship since January 1942), en route from New York on September 23, 1942, with a stopover in Liverpool (England), to Clyde (Scotland), where some 1,500 British soldiers embarked for Algeria, arriving in a convoy of 17 ships on November 14. Later the Coamo left for Gibraltar and from there to Land’s End, in Cornwall, England. On December 1, 1942, the British Admiralty ordered the Coamo to abandon the convoy and return to New York via the relatively safe Bermuda route. The next day she was fatally torpedoed, some 200 miles off the west coast of Ireland, by U-604, commanded by Horst Höltring. All 186 men on board died – 11 officers, 122 crew members, 37 armed guards and 16 soldiers from the Army that the ship was transporting – including Uribe, 45 years old. This was the largest single loss of a merchant crew on any US-flagged merchant ship during WWII.

The Battle of the Atlantic, which began in 1939, has gone down in history as one of the largest and longest-running naval battles in WWII. The fight for maritime hegemony, the blockade of the United Kingdom by Germany, and the counter-blockade of Germany by the allied powers placed in the center of the bullseye the convoys that formed from the warships and the merchant ships they escorted in their mission to transport all kinds of supplies to the United Kingdom and allied troops in preparation for the eventual invasion of occupied Europe. The military war also became a logistical war, of great strategic importance, which finally tilted to the Allied side with a cost in the lives of some 36,200 Army soldiers and some 36,000 merchant sailors, and the loss of some 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships.

Among the Basque sailors that we have identified in the Atlantic is Daniel Solaegui Mugartegui. Born in 1916 in Fallon, Nevada, to Bizkaian parents, he joined the Merchant Marine in San Francisco, California. He was part of the crew of one of the new Liberty-class artillery cargo ships, the SS Melville E. Stone which was launched on July 24, 1943. Solaegui was a qualified member of the engine room where he worked as a fireman. The Melville E. Stone carried a 101 mm gun, a 75 mm gun, and 8 20 mm anti-aircraft guns, which were commissioned by a crew of armed Guard gunners embarked for that purpose, but that was no problem for the German submarines, and less when traveling without an escort. She was destined to make the route between Antofagasta (Chile) and New York, and had already crossed the Panama Canal when she was torpedoed on November 24, 1943 by U-516 under the command of Lieutenant Commander Hans-Rutger Tillessen. The 88 men who made up the crew and the passengers (military personnel) abandoned the ship, but the suction caused by the sinking ship dragged 15 people to the bottom of the Caribbean, including Solaegui. He was 27 years old. Two of Solaegui’s brothers served in the army: Joseph (1925-2004) graduated with the rank of first-class soldier and Frank (1921-2009) became a lieutenant in the 101st Airborne Division.

Straddling the European and Asian theaters of operations is Miguel “Mikel” Usatorre Royo, born in Lekeitio, Bizkaia in 1913. Like his brothers (Marcelino Juan, Vicente and José María), he was a career merchant sailor when his life was abruptly interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War in Spain. He fought with the Basque Army and was taken prisoner by the rebel troops. His brother Marcelino (1902-1966) also participated in the war and became a lieutenant colonel in the 27th Division of the People’s Army. After the military defeat, Marcelino went into exile to France and later to the Soviet Union, serving in the Red Army between 1939 and 1947. Marcelino graduated with the rank of lieutenant colonel. After serving time in forced labor camps, Mikel was finally able, after four years of waiting, to embark as a sailor bound for Buenos Aires, Argentina. Later he went to sea as a boatswain on the Argentine-flagged tanker Victoria. Despite their neutrality, on the way to New Jersey the Victoria was torpedoed twice (by mistake according to the German authorities in response to the Argentine government after the attack) on April 18, 1942, by U-201, commanded by Adalbert Schnee. The crew left the ship in two life rafts, being rescued days later. To their aid came the minesweeper USS Owl, which towed them to the Island of Bermuda, where they were able to partially repair the Victoria. Once repaired, she was escorted by the destroyers USS Swanson and USS Nicholson until a tugboat took over for the tanker. The Victoria and crew arrived in New York on April 21. Mikel was 28 years old.

On American soil, Mikel decided to enlist on a ship dedicated to the transport of American troops bound for the United Kingdom, in preparation for the invasion of Normandy, work that he would later carry out in the Pacific, in the face of possible invasions of the islands occupied by Japan (from the Philippines to Okinawa). After the war, he was posted to the Philippines and, shortly after, to Okinawa, where he worked as a captain and portmaster for 25 years for the Second Logistics Command of the US Army. For a time, he met another Basque merchant seaman, Antón Brouard, in Okinawa. Mikel received the Two-Star Combat Medal, among other decorations. In 1950, he obtained American citizenship. He passed away in 2000, aged 86, in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

The aforementioned Antonio “Antón” Brouard Pérez de Oxinalde, born like Mikel Usatorre in Lekeitio in 1916, was also a professional merchant captain. After the coup in Spain, Brouard as second officer of the yacht El Vita – under the US flag and owned by the Basque-Filipino financier and US citizen, Marino Gamboa – participated in the transport of a shipment of seized valuables and precious metals by the General Reparations Fund during the Civil War, between Le Havre, in France and Veracruz, Mexico, where it arrived on March 23, 1939. The so-called “Vita treasure” was destined, originally, for the Service of Evacuation of the Spanish Republicans, but ultimately it would be yielded to the Board of Aid to the Spanish Republicans. Both the captain, José Ordorica Ruíz de Asúa, his first officer, Isaac Echave, and the rest of the yacht’s crew were from Lekeitio. Despite having received Mexican nationality from Lázaro Cárdenas himself, Brouard was unable to captain ships, so after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he decided to work for the USMM, eager to recruit experienced sailors. He served in the Pacific where he supplied troops during the war. After WWII, he was sent to Okinawa as a port pilot, a position he held for five years. He passed away in his hometown in 1994, at the age of 78 (1).

The American Merchant Marine at War association estimates the loss of about 8,400 men out of a total of 243,000 merchant seamen, as identified by the War Maritime Transportation Department in 1946, to which should be added another 1,000 wounded who would eventually die. Altogether, some 12,000 were injured and some 700 became prisoners of war. Almost half of all casualties occurred in 1942. Among the Armed Guards, assigned to merchant ships since the summer of 1942, about 2,200 perished and 1,100 were wounded. The USMM suffered a higher casualty rate than any branch of the military during the war. One in 26 sailors died or were reported missing, much higher than casualties in the Armed Forces, where one in 133 soldiers died or disappeared. The overall loss by the USMM was very similar to that of the Marines, who had a ratio of 1 in 34. Between 1939 to 1945, some 1,600 US-flagged merchant ships (6 million tons) were sunk, while hundreds of other vessels were damaged.

Despite their great sacrifice, it took 43 years for the federal government – after a lawsuit by the American Merchant Mariner association – to recognize USMM survivors as war veterans that could receive, albeit partially, the benefits related to this recognition. However, today it is still common to observe how they are not included in military monuments or memorials or in public tributes. In 2018, US Congressman John Garamendi, grandson of Bizkaia, sponsored and promoted the “Merchant Mariners of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2020,” which was approved by Congress on September 19 of 2019, and was ratified by the Senate on December 21. Therefore, the bill became law once it was signed by President Donald Trump on March 14, 2020. The goal of this legislation is to award, collectively, a Congressional Gold Medal – one of the highest honors in the United States – to the merchant seamen who supported the armed forces during WWII. From the Sancho de Beurko Association we congratulate the happy ending of the initiative and we hope that our public institutions and professional associations of merchant seafarers will join in this public recognition as part of our historical legacy. We hope this article serves as a small tribute to the merchant marines of WWII and that it can contribute to their knowledge and encourage young historians to investigate the role played by the thousands of sailors and merchant marines without whose effort and sacrifice the victory against totalitarianism would not have been possible.

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.