Is it better to be good or lucky? Success in business often requires a bit of both. Or, maybe better said, luck comes to those who are prepared for it: “I’m a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it” (Coleman Cox). “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity” (Seneca). Sometimes, things happen that we could never have anticipated, but if we are in the right place and time, we can leverage that into success. Such is the story of Simon Gurtubay, who parlayed a typo in a telegram into one of Bilbao’s first fortunes.

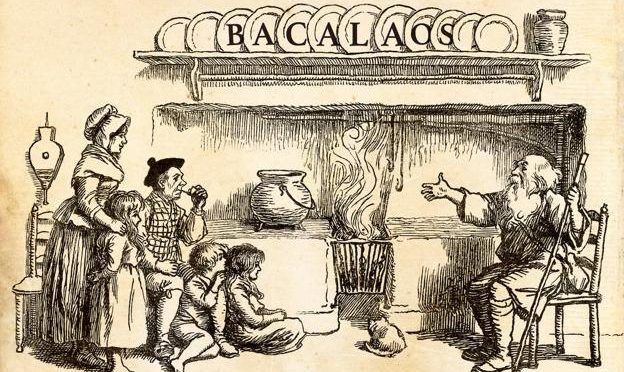

- Simon Gurtubay Zubero was born in Igorre, a small town just to the southeast of Bilbao that is today the home of about 4000 people, in May, 1800. His parents, Baltasar Gurtubay and María Zubero, were laborers. Gurtubay was uneducated; supposedly, his son had to sign documents for him as he couldn’t even sign his own name. As a young man, he moved to Bilbao, where he dedicated himself to the fur trade. The story goes that, in 1836 during the middle of First Carlist War, Gurtubay sent a telegram where he ordered “100 o 120 bacalao” — 100 or 120 pieces of cod. However, his telegram was misinterpreted and, instead of “100 o 120,” the “o,” maybe missing the accent (o versus ó), was read as a “0” and he ended up receiving “1,000,120” pieces instead.

- At first, Simon was almost suicidal as there was no way he could pay for all of that fish. He tried to sell it in various parts of Spain, but had no luck. However, Bilbao was under siege during the war and food became scarce. Soon, Gurtubay had a market for his fish. Cod soon became a staple of the Bilbainos and the Bizkaians and Gurtubay became a rich man. And Basques, being the enterprising people they are, took advantage of all that cod and the now-famous bacalao a la vizcaína was born. Or maybe bacalao al pil-pil. At least that’s the story.

- Ana Vega Pérez de Arlucea argues that there are several inconsistencies with this story. First, olive oil – the foundation of bacalao a la vizcaína – would have been too expensive for the majority of people at the time. Second, there is no record that Gurtubay received such a large shipment. Third, bacalao was already popular in Bizkaia at the time. And, last, the sieges of Bilbao didn’t last long enough to cause such shortages (though the second one, in 1836, did last nearly two months). These are all circumstantial arguments, but suggest that Gurtubay’s story may have some elements of fiction mixed in with fact.

- What is certain is that Gurtubay did become rich, and that he then became a pillar of Bilbao. He founded the company “Gurtubay e Hijos” and participated in the founding of the Banco de Bilbao. He was also involved in the birth of the Bilbao-Tudela railway and the Bilbao Chamber of Commerce. He died on April 14, 1872.

Primary sources: Gurtubay, Mertxe. GURTUBAY ZUBERO, Simón. Enciclopedia Auñamendi. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/gurtubay-zubero-simon/ar-76776/; Vega Pérez de Arlucea, Ana, La falsa leyenda del origen del bacalao (II): así surgió el mito asociado a los Guturbay, El Correo; Alma de Herrero

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You know that this is a legend, right? In other words, fake news.

I saw someone throw some doubt on the story, but it wasn’t conclusive (and I do note that perspective in the post). Is there something more conclusive saying it is fake? If so, I’ll update the post.