Most of us who have Basque heritage in the western United States trace that connection to the Basque sheepherders that, in years past, dotted the entire western landscape. My dad came over when he was 18 years old, drawn by the promise of economic opportunity and his three uncles who were already here herding. These men and women were the foundation of a vibrant diaspora that has garnered the respect of their neighbors and become pillars of their community.

- Livestock was introduced to what we now call the Basque Country sometime around 2500 BCE through North Africa. The importance of livestock to the early Basque economy and lifestyle is attested by the fact that the word for wealth – aberastasuna – literally means “possession of herds.” In fact, herding predates agriculture in the Basque Country, with more native words associated with livestock than are used in agriculture.

- In the Basque Country, there were large herds of sheep — in excess of hundreds of thousands — through which some Basques could make their fortune. Herders would partner until their herds got so big and then split into two new bands, increasing their individual success. In 1841, new customs were implemented at the French-Spanish border which hindered the herding model that Basques had developed. Some left, going to places like Argentina, where they took their model and proved very successful. Eventually, some of these Basques made their way to California, particularly after gold was discovered, and established a similar system there. In fact, early herders were paid in sheep, not money, and this let them establish their own herds.

- Despite this long history with livestock, and sheep in particular, many of the Basques that immigrated to the western United States didn’t have so much experience with sheep. If they did, they had watched small family herds that they took to nearby pastures. They were not accustomed to the long transhumance practiced in the United States, in which animals were moved long distances between seasons.

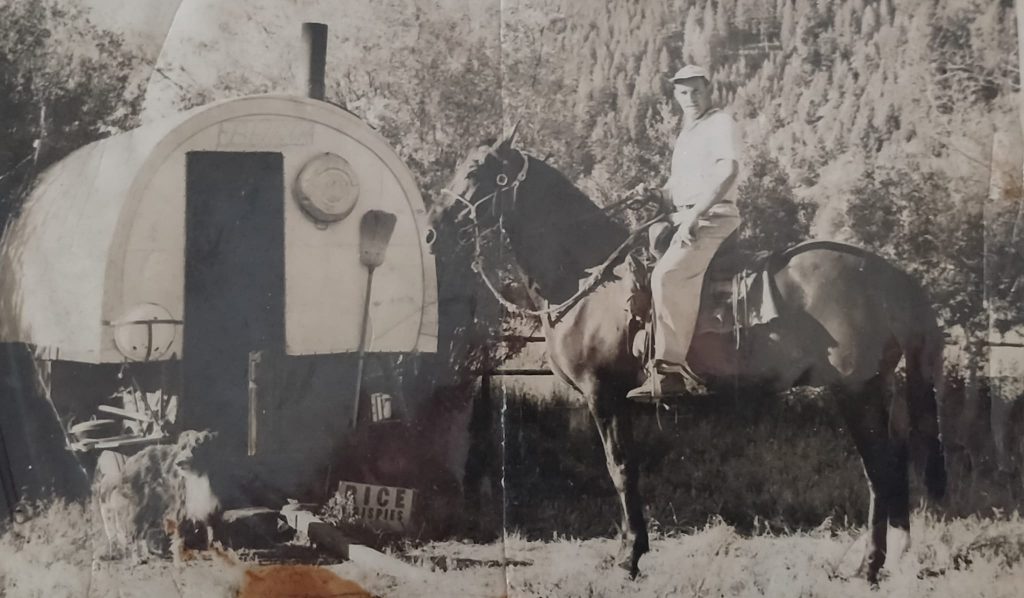

- Since at least the early 1900s, Basques would come to the United States on a three-year contract to herd sheep. They needed little, as they wouldn’t have a permanent home, and most were single.

- While today, the Basque sheepherder is a romantic figure, that wasn’t always the case. In the late 1800s and 1900s, they were looked down upon, particularly by cattle people. They were called “dirty black Basques” and other names. Because they were foreign and they didn’t buy land, American cattle ranchers did not think the herders deserved the same rights as they did. This tension could lead to violence. Laws such as the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 protected grazing rights for ranchers, but not sheepherders.

- Further, immigration from Spain was limited – in 1924 only 131 Spanish could enter the country. That changed in 1950, when Nevada Senator Patrick McCarran sponsored a bill that eventually became the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 and which boosted recruitment of Spanish herders. Again, herders could come on a three-year contract, and potentially return a second time. The three-year contract was enforced to ensure that the herders didn’t reach the five-year residency qualification mark. The Western Range Association, established in 1960, led the selection of herders and this happened in the consulate in Bilbao, leading to almost exclusive selection of Basques as new herders.

- The three-year contracts were for $200-$300 per month. The contracts also stipulated that the herder had to pay their way to the United States (though the Association often paid and then took the costs from wages) and could not work for anyone other than the Association. Amongst other things, the Association promised to pay funeral expenses if the herder died during employment. The herders could also gain permanent residency through their contracts and, in 1976, some 2000 herders became permanent residents. Eventually, however, the economic situation in Spain improved enough such that emigrating to the United States was no longer attractive.

- Life as a herder was lonely. Young men would be put to work in the mountains, often alone or with a partner. While a foreman would come to deliver supplies periodically, it was still a lonely life. Many herders went crazy from the isolation – they would become “sagebrushed.” Some simply couldn’t handle it and committed suicide – my dad told me of one herder that returned to the Basque Country and ended up shooting himself in his ancestral baserri, not far from where my dad grew up. These herders also left their mark on the landscape through their carvings on the aspen trees, a visual historical record that is still providing new insight into their lives.

Primary sources: Arzac Iturria, Eduardo. PASTOREO. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/pastoreo/ar-122884/; Estornés Lasa, Mariano; Totoricagüena Egurrola, Gloria Pilar. Estados Unidos de América. Oeste americano. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/estados-unidos-de-america-oeste-americano/ar-50446/; Carving Out History: The Basque Aspens, by Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Eskerrik asko Blas. Ondo dator batzuetan pentsatzea eta konturatzea nondik gatozen. Besarkada handi bat.

very interesting. I”m writing a novel set in the Owyhees; a Basque man is a central character, so I’ve been doing a lot of research on the sheep business, the times (1928-1931), & the culture. It’s intriguing and rich…I love it! And I love the Basque Museum! Thank you for your newsletter!!