This article original appeared in Spanish at EuskalKultura.eus.

Interrogated in Budapest

“Alfonso Garde, Corporal, 3835273.” Those were the only words that came out of his mouth in response to the demands of his interrogator. Under the Geneva Convention, a prisoner of war only had to provide his name, rank, and serial number. “Alfonso Garde, Corporal, 3835273.” The enthusiasm with which he had enlisted in the Air Force a year earlier at Fort Bliss, Texas, flew through his head. His dream was to be a pilot. He had been called up three months after his 18th birthday. “Like most 18-year-old men at that time, I could hardly wait to put on the uniform,” Alfonso confessed in his memoirs written 40 years after his captivity during World War II [1].

At the interrogation center in Budapest, Hungary, where he had been taken after his capture, he recalled the last time he was able to see his loved ones at the family ranch in Vaughn, New Mexico. It was early July, 1944. Alfonso and the rest of his crewmates had been granted three days leave. During his short visit, he told his siblings, but not his parents, that he was going to be sent to the European front. “I saw no need for them to worry,” Alfonso wrote [2]. It was perhaps premonitory. In fact, it would not be until January, 1945, when the US War Department made public that Alfonso was a prisoner of war in Germany, six months having already elapsed since the beginning of his captivity.

His Plane, Shot Down

“We had been forewarned that prisoner war interrogations could be very rough,” Alfonso recounted. “We were spared by the fact that the war had taken a turn in favor of the Allies. The interrogation finally arrived – it consisted of them telling us more about ourselves than we ourselves knew […] The interrogation room walls were lined up with information on all our units” [3]. It was there that he learned of the death of six of his ten fellow crew members of the B-24, along with the photographer who flew with them to record the results of the bombing. Alfonso had been uninjured, but the two waist gunners had suffered burns to the face and arms while the upper turret gunner had a head wound.

Budapest, a city that, like the rest of the country, had been occupied by German troops in March, 1944, was neither the beginning nor the end of Alfonso’s odyssey. So let’s go to the beginning of the story.

To the European Front

After passing through Fort Bliss in August, 1943, the young Basque-American recruit was sent to the Aerial Gunnery School in Harlingen, Texas, where he was trained as a ball turret gunner – a spherical turret made of plexiglass perched on the belly of a B-24 Liberator heavy bomber with room for one person manning two .50-caliber Browning machine guns. His dream of becoming a pilot had come to an end.

In April, 1944, Alfonso and the rest of the crew were posted to Pueblo, Colorado, for combat training. Returning from their brief three-day leave, they flew to Bangor, Maine, in mid-July, where they picked up their new B-24 bomber, which they named “Patsy Ann,” after the pilot’s girlfriend. They left the US in their “Patsy Ann” on July 21, 1944, via the Azores Islands and North Africa, reaching their final destination in Foggia, southeastern Italy, on August 8, 1944. There they joined the 724 Squadron of the 451st Bombardment Group based at the Castelluccio Airfield, an agricultural area located 14 kilometers from Foggia.

Ring-side Seat to the Allied Invasion

Despite the fact that they lacked two weeks of training, their first mission took place the day after their arrival on Italian soil. The war could not wait. Their objective was to prepare for the Allied invasion of southern France, which took place on August 15, 1944, and which they witnessed, as Alfonso described, “What a ring-side seat! We saw our battleships pounding the enemy installations as hundreds of barges and boats discharged our troops unto the beaches” [4].

Tragically, on August 23, 1944, Alfonso’s aircraft was hit by enemy planes and finally shot down when his group of bombers, made up of 25 planes, tried to destroy the Markersdorf Airfield, 65 kilometers from Vienna, to prevent the Luftwaffe from using it. The 451st Group lost 9 aircraft on that mission and earned the coveted Presidential Unit Citation. The German fighters had made an appearance under the cover of clouds and the B-24s were very vulnerable to the power of the 20mm cannons of the Focke Wulf Fw 190s. Garde’s plane – “Hard to Get,” piloted by Lieutenant James H. Powers – had been hit on the left wing and plunged uncontrollably towards the ground. The other bombers in the squadron counted up to eight parachutes, but six crew members, including the pilot, would not survive the incident: Lieutenants Ray F. Chisholm, Sidney Samet and Merle E. Vanderhorst and Corporals Franklin D. Atwood and Leonard L. Wagner [5].

Show Down and Captured

This is how Alfonso remembers the demolition of his plane and the fortune of getting out alive:

“Abandon the ship!” The pilot screamed. Time was of essence—we were flying at 20,000 feet and I no longer had an oxygen mask. The whole rear end of the plane had been blown away. The only other possible escape was through the bomb bay, which was still loaded with hundreds of small fragmentary bombs. Before the doors were completely open, I jumped. The bombs were also released, so the bombs and I came out together. All I remember is that I pulled the handle of my parachute. I passed out for the lack of oxygen. My ‘ride’ must have lasted about 30 minutes [6].

The inevitable impact against the ground was softened by the treetops that caught the parachute. “As I pondered how to get the tangled parachute down from the tree, I heard two distinct clicks behind me. I turned around to see two rifles aimed at my head. Behind the guns were a middle-aged Austrian farmer and a young man. Would they pull the trigger?” [7]. The two men drove Alfonso to their farm, an hour’s walk away. He was hoping they would help him escape or hide from the authorities. However, all hope was dashed when they went to look for a soldier who escorted him to the town jail. At dusk he was joined by his crewmates.

Later they were taken to a nearby city where there were a large number of airmen who, like them, had also been shot down. “We were then loaded into boxcars like animals for our next destination, which turned out to be Budapest, Hungary – the interrogation center” [8]. Their arrival in the city was not well received. The city had been heavily bombarded the previous days, and the citizens were crying out for revenge. The transfer from the train station to the prison was in open trucks. In their wake, stones were thrown at them. “The only thing that saved us was the fact that the trucks kept moving and the Germans guards placed themselves between us and the civilians,” Alfonso wrote with some relief [9].

The Stalag Luft IV Prisoner of War Camp

After two weeks in Budapest, Alfonso and his companions, along with many other airmen, were sent to the Stalag Luft IV prison camp, in Gross-Tychow, Pomerania (now Tychowo, Poland), which was administered by the German Air Force for Allied aircrews.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

More than 120,000 Americans were taken prisoners of war during the bellicose conflict. Most of them, some 94,000, spent their captivity in the almost hundred camps built by the Nazi regime throughout their country and the occupied territory in Europe.

The journey to Stalag Luft IV took four days, passing through bombed-out Berlin, on a crowded freight train. “We could sit,” Alfonso related, “but we couldn’t lie down. There were no bathroom facilities, and, after a couple of days, it was hell to be in those cars” [10]. The prison camp consisted of four compounds – three for Americans and one for the British – for a total of 10,000 airmen.

Five Months in the Prison Camp

By Alfonso’s account, the German authorities respected the Geneva Convention, so there was no forced labor. However, the shortage of food was a serious problem. “We survived because the American Red Cross food parcels. Life in camp was not bad as long as we behaved. Since we were not forced to work, we had much time to kill. Life was dull, but at least we were ‘safe’. This went on for some five months. This situation was to suddenly change. The Russians began their offensive towards the west. The Germans had no intentions of letting the Russians liberate 10,000 American [and British] airmen” [11].

Faced with the continuous advance of the Soviet Army on the Eastern Front, Germany decided to evacuate the prisoners to the heart of the Third Reich. It is estimated that between January and April, 1945, 80,000 Allied prisoners were forced to walk west in the middle of one of the bloodiest winters of the war, without food or adequate clothing, and afflicted by disease. These forced marches were known as “the Black March” or “the Death March.” About 3,500 Allied soldiers perished as a result of them.

The Death March

On February 6, 1945, some 8,000 prisoners from Stalag Luft IV, including Alfonso, set out on a march of more than 800 kilometers – 500 miles – on foot, during which hundreds of soldiers died. The memory of that time remained very vivid in Alfonso’s mind for the rest of his life.

Early one morning we were informed we would be evacuating the camp. The next three months were to be three months of pure hell. We left camp with the cloths we were wearing, a blanket, and whatever we could carry on our backs. Our problems began almost immediately. The bitter cold brought much influenza and illness. We battle frostbite, fever, and pneumonia. Before long we were infested with body lice. Hunger was the worst part. Because of drinking impure water, dysentery ran rampant among the prisoners. I became quite ill but survived only because I was literally carried for a week by some of my befriended ‘cell’ mates. We walked from daylight to darkness when we would drop from exhaustion and hunger. For substance we had little to eat but boiled potatoes, kohlrabies picked up along the way and loaves of black brot (bread), which had to be divided twenty ways. We survived day-to-day from meager handouts given to us by civilians along the road. I traded my watch for a loaf of bread and a piece of sausage. My class ring went for a dozen boiled eggs [12].

The American and British troops continued their advance towards German territory from the west. “The sound of war and the rumble of tanks were more evident every day. What a sight to behold as the British tanks appeared over the horizon! The day was May 2, 1945 – the happiest day of our lives after 250 days of captivity,” Alfonso exclaimed in his writings [13]. Five days before he had turned 20 years old. Left to their own devices, the prisoners of Stalag Luft IV began their last march towards the British zone. Alfonso’s tragic odyssey was coming to an end. Germany finally surrendered to the Allies on May 8, 1945. By the middle of that month, all surviving American prisoners were under Allied control. Evacuated to the French port of Le Havre, he boarded a troop transport ship for the United States. Alfonso arrived at the Port of New York on June 12, 1945. Thirty-two years earlier, his father, Mauricio Garde Echandi, a native of Urzainki, Nafarroa, had followed the same path, at only 19 years of age.

Back to Vaughn

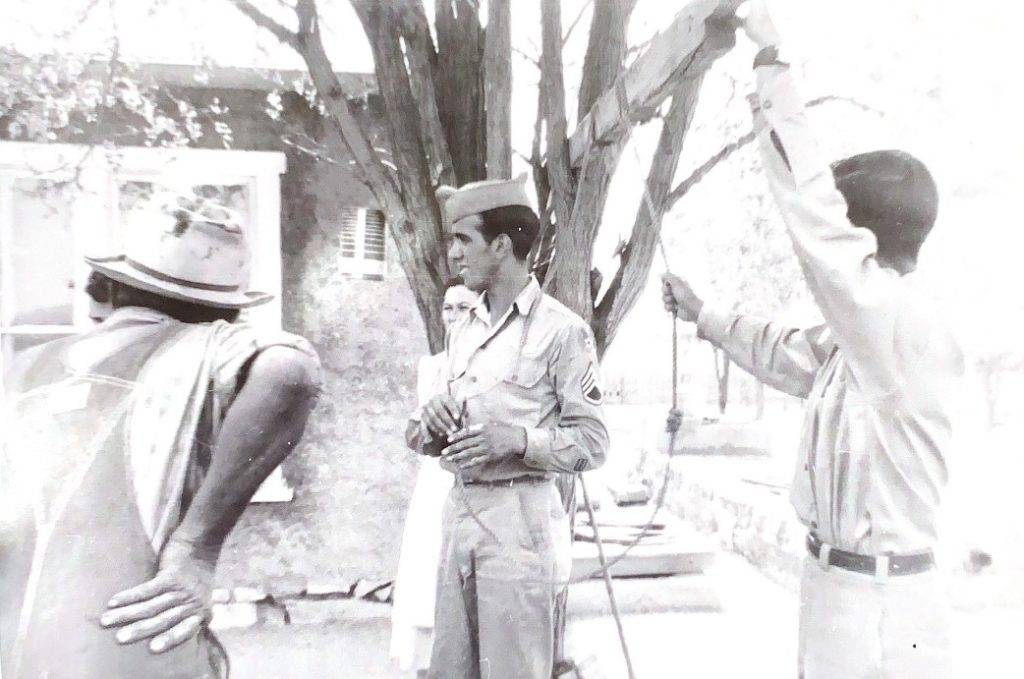

Alfonso was discharged with honors on October 17, 1945, in Roswell, New Mexico, with the rank of sergeant. He was awarded the Bronze Star for the campaigns in Central Europe, the Rhineland, Northern France, Southern France, and for the Balkan Air Combat. He received the ribbons for the Theater of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. He in turn received the Air Medal (awarded in October 1944 during his captivity) and the Presidential Unit Citation.

Upon his return, his parents and siblings were waiting for him at the family home in Vaughn. His mother, Emilia Marcilla Anaut, from Nafarroa and born in Isaba in 1901, had arrived in the US with her father in 1916. Her father tragically died in a snow storm while tending a flock of sheep in the 1920s. More than one hundred residents of Roncalese town of Isaba emigrated to New Mexico during the first two decades of the 20th century. Most of them worked in the agricultural and livestock sector.

Emilia and Mauricio married around 1919, establishing their residence in Vaughn, where Mauricio operated a sheep ranch. The distance that separates the hometowns of Emilia and Mauritius is less than 4 kilometers. Paradoxically, they met thousands of kilometers from their native Roncal Valley. During their marriage they had eight children, all of them born in Vaughn: Mariana (1920-1943), Jesusa “Susie” (1921-2011), Mauricio Jr. (1923-2003), Alfonso Justo, Inez (1927-1998), Emilia ( 1928-1975), Elena “Helen” (1930), and Raymond (1940).

Mauricio Jr. was also called up for duty after graduating from the Vaughn Institute. During the war he served as a Military Police in the Army. All the children of Emilia and Mauricio graduated from college, which facilitated their entry into the middle class. The socioeconomic rise of the first Basque generation born in the country was evident.

In 1949, Alfonso married Delia Dávila and they had three children. He retired in 1981, after having developed a brilliant career in the world of education. In the 1950s he was superintendent of the Vaughn schools, and until the mid-1960s he was superintendent of the Belen, New Mexico, schools. He later worked for a year for the New Mexico State Department of Education in Santa Fe, and from 1968, Alfonso carried out his professional work as director of transportation and district business manager for Belen schools.

As his daughter Sarah told us, “My father never spoke about his experience at war. He would only announce the anniversary date of when he was shot down! My dad was typical of The Greatest Generation!” [14]. Alfonso last reviewed his memoirs in 1990. “After reflecting for forty years on my unusual adventure, I have decided to put my thoughts in writing,” Alfonso wrote. “Why? I really don´t know. It was not a feeling of guilt or shame for having been captured. It was probably more a feeling of sorrow for my crew mates who did not return, as well as the thousands of young men that gave it their all” [15].

Alfonso Garde Marcilla passed away at the age of 66, on February 17, 1992 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. May this article serve as a small tribute to Alfonso’s companions who lost their lives 78 years ago.

References

[1-4, 6-15] Garde, Alfonso. (August 1984, revised August 1990). “Reflections 40 Years Later”. P. 3, 4, 9, 5-6, 6-7, 7, 9, 10, 10-11, 12, and 2.

[5] Report of the mission on Markersdorf (Austria) of August 23, 1944 in nº 9 of the bulletin of former members of the 451st Bombardment Group (https://www.451st.org/Ad%20Lib/Pdfs/Issue%209.pdf).

[14] Interview by the authors with Sarah Garde (January and February 2023).

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’ve heard many stories of the Garde’s from Vaughan. Gene Franchini‘s family who owned the store in South Albuquerque told me great stories about my grandparents, and the Garde’s coming to the Franchini store to buy the wine! We have many connections to the Basques in Vaughn and this story warms my heart! #erramouspe #orhategary (Lorin Erramouspe Abbey, Santa Fe NM)

Thanks for sharing Lorin!