A couple of weeks ago, on the 84th anniversary of the bombing of Gernika, I posted about Picasso’s Guernica, and how it was inspired by those horrific events. Eneko Sagarbide and Jabier Aldekozea pointed out that Gernika was not the only, nor even the first, Basque city bombed during the Spanish Civil War. In fact, as emphasized in his book “Arrasaré Vizcaya”. 2000 bombardeos aéreos en Euskadi (1936-1937), Xabier Irujo recounts that the Basque Country was bombed some 2000 and several important Basque cities were devastated as a result.

- Eibar, just on the Gipuzkoa side of the border with Bizkaia, was first bombed on August 28, 1936, and was bombed fifteen times — twelve between the dates of April 22 and 25, 1937 — until the city finally fell on April 26, 1937, the same day that Gernika was bombed. According to the book The Civil War in Eibar and Elgeta, by Jesús Gutiérrez, the population was reduced to about 150 people from some 13,000, many due to casualties and evacuations. In the urban center, out of 488 buildings, 156 were completely destroyed and another 101 were damaged. 840 out of 1750 homes were destroyed. After the war, the population had been reduced to 5,000.

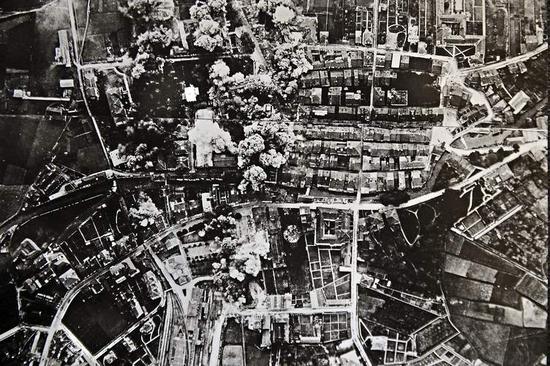

- Durango, Bizkaia, was bombed on March 31, 1937 by both the Italian Aviazione Legionaria and the German Legion Condor. Durango was a road and rail junction between Bilbao and the front lines of the war. Two of the town’s churches were bombed while conducting mass, leading to the death of 14 nuns and a priest. Estimates put the civilian death toll at about 250 people. Elorrio, a nearby tourist destination known for its spas, was bombed on the same day. After Durango, the civilian populace began to realize that their houses were not safe against the bombings and began taking refuge in, amongst other places, local caves.

- My dad’s home town of Gerrikaitz, and the associated town of Arbatzegi, which together comprise Munitibar, was bombed in the morning of April 26, 1937, just hours before Gernika. 11 people were killed. The nearby towns of Markina, Ziortza-Bolibar, Arratzu, Muxika, and Errigoiti were also bombed during this wave. In fact, Markina was the first Basque city bombed by air in the war, on September 29, 1936, but this first bombing caused little damage. In fact, people were more curious than anything when these first bombings and attacks occurred as they were fascinated by the planes flying overhead. However, that all changed when 6 people were killed by such attacks in Markina in October, 1936. By the end of the war, Markina had been bombed at least 20 times.

- The Bizkaian towns of Etxebarria and Berriatua were bombed starting in October, 1936. In fact, Mount Kalamua, part of the front lines and where the towns of Markina, Etxebarria, and Elgoibar converge, was bombed nearly every day between October 1 and 20 by Italian planes.

- These are only a few of the bombings that occurred against the Basque populace. A very comprehensive list of all of the bombings, both aerial and land by both sides, can be found here: Atlas de Bombardeos en Euskadi (1936-1937).

Primary sources: History of Éibar, second.wiki; Bombing of Durango, Wikipedia; Bombardeos en Euskadi (1936-1937); Bombardeos de la Guerra Civil (an Excel spreadsheet listing the bombings, by both sides, during the war)

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Durango was the basque city hardest hit by Aviazione Legionaria. There were around 250 deaths in Gernika and slightly over 300 in Durango.

It is hardly understandable why Franco and his allies decided to bomb Durango, whose inhabitants were very conservative and regarded with undisguised simpathy the coup of general Mola.

In fact, a significant part of the older Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) leaders and the military insurgents shared the same views and it was the lehendakari (president) José Antonio Aguirre who at the last minute sided with the Spanish Republic.

Anyway the Italians added salt to injury when, hours after the raid on Durango, Mussolini’s fighters, flying low level to avoid detection, returned to the town and straffed the funeral procession for those killed in the morning. But this fact diluted into oblivion under Franco’s regime and modern historians have resurfaced it.

This proves two things: that war is always cruel and that only the patience of children is shorter than the memory of men.