This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario on October 9, 2019.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

The bertsolaris Fernando Aire Etxart “Xalbador” from Nafarroa Beherea and Mattin Treku Inharga of Lapurdi arrived in the United States in June 1960 to participate for a month in the Basque festivals of La Puente, Bakersfield (both in California), and Reno (Nevada), as well as the festival hosted by the French association Les Jardiniers Français de San Francisco (California), which was brought together, among others, a large number of Basques and Bearnais. On June 19, to the dismay of the artists and their compatriots and before an audience of 2,500 people, the power to their microphones was cut off during the performance of the two berstolaris at the Les Jardiniers event. Some said it was intentional and while others called it an accident.

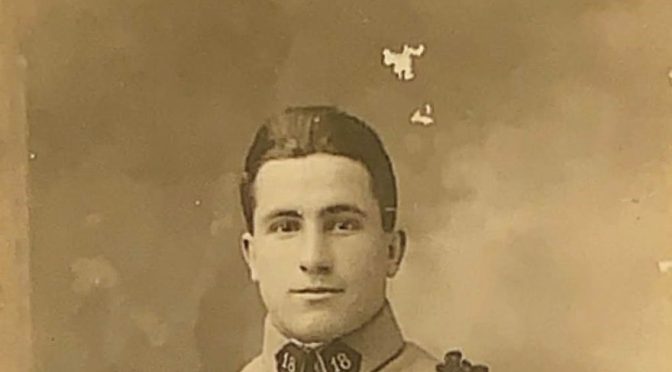

Be that as it may, the reaction of the youngest in attendance, mainly of Nafarroa Beherea origin, was immediate. They decided to establish, before the end of June, their own organization under the leadership of Claude Berhouet, a native of Donazaharre (Nafarroa Beherea) and owner of the Hotel de France in the city of San Francisco. The Basque Club of California was born. Its bylaws include its purpose and objectives: “to promote the well-being of all people in the Basque region of France and Spain by birth or descent, and to promote their social, recreational, intellectual, cultural, physical, and moral well-being.” Among the founding members of this new Basque diaspora association was Baptiste Etchepare, a veteran of the US Army of World War II (WWII). Born in 1908 in Mendibe, Nafarroa Beherea, he immigrated to the United States at the age of 23. At the time of his enlistment he was working as a lumberjack in Standard, California. Life in the barracks was not strange for Baptiste as he had served in the French army before emigrating. He obtained US citizenship at Chanute Air Force Base, Illinois, in 1943 with the “slight” anecdote that his name was officially changed to “Baptis Etche.” He was discharged with honors on October 10, 1945 with the rank of Private First Class and received the Medal of Good Conduct.

Just before the end of the war, Baptiste married Mary Rita Iturreria Gamboa, born in Patterson, California, in 1919, to Nafarroa parents, José Ignacio “Joe” Iturreria and Josefa “Josephine” Gamboa, from Erratzu and Sunbilla, respectively. As a result of the Great Depression, after finishing high school Rita decided to leave her hometown for San Francisco, where she met her future husband at a dance in 1942. Then the war broke out and the sunsets darkened as blackouts were imposed due to fear of air raids by the Japanese imperial forces, a situation that Steven Spielberg captured in his film 1941. Still life went on.

After the war, Baptiste worked as a truck driver and after a few years the family moved from San Francisco to the nearby town of Millbrae, where they raised their sons James and Robert. While the couple spoke Basque, the main language in the house was English. Rita — whom the co-author of this blog, Pedro J. Oiarzabal, interviewed in 2015 within the framework of NABO’s Oral History Program “Memoria Bizia” [1] — described the world of her childhood and youth, mostly agricultural in small towns that has largely disappeared, in which the emigrants, both Basque and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees were gradually integrating socio-economically into American society through great effort, sacrifice, and self-improvement. Basque and Navarrese emigration to California had flourished from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century. WWII became perhaps one of the most important elements driving the incorporation of non-Anglo-Saxon immigrant communities into postwar American society.

Rita’s father immigrated to the United States in 1912, at the age of 23, and her mother arrived in 1916 at the age of 19. Her parents met in Los Angeles, California, where they worked on the same citrus ranch owned by a Basque family. After Rita’s parents married in 1918 in Los Angeles, they moved to Patterson in 1919. Her father and his childhood friend from Erratzu, Juan Felipe Maya Salaburu, established a dairy farm in 1919. Rita’s three younger siblings were also born in Patterson and raised on their parents’ dairy: Graciano “Gracian” was born in 1920, Manuel John in 1921 and Felipe “Philip” in 1922.

Rita, like many of the children of non-English-speaking migrant parents, typically only knew their parents’ language until they were in school. She remembers how in her house they only spoke Basque, although her siblings had a bit more luck going to school since she was able to teach them some English. Even as a child she learned Portuguese to be able to communicate with her Portuguese neighbors.

During WWII, the family business suffered a major setback. The federal government confiscated their cows, under pretext, and they were slaughtered in order to feed the troops. The war not only dragged Rita’s boyfriend into military service, but also her three brothers and the son of her father’s partner, Joseph John Maya Gortari, born in Patterson in 1922. His parents, Juan Felipe Maya and Amalia Pía Gortari Ylzauspe from Azpilkueta, Nafarroa, had emigrated to the United States in 1910 and 1914. Joseph was working on the family farm when he enlisted in the Air Force on September 30, 1942, serving at Marfa Air Force Base in Texas.

Six days earlier, his childhood friend Manuel Iturreria had also enlisted in the Air Force. However, Manuel was sent to England, where he served as crew chief and tail gunner on a bomber in the European theater of operations. Manuel barely survived the downing of his plane in which the rest of his crew died. They were too close to the ground to be able to use the parachutes, so Manuel waited until the plane was low enough to jump before crashing. He was injured in the jump, but survived. He had participated in more than twenty missions. Manuel and his brother Gracián, both stationed in Europe, met in England before being repatriated to the US from France. Gracián had enlisted in the army in August 1942 and participated in the invasion of Normandy on D+1 (the day after D Day). Finally, the youngest of the Philip brothers was drafted into the army in July 1946 as a replacement after demobilization of the troops with the end of the conflict. As the third child and with two brothers who were already serving in the military, he was not sent abroad. Asked about the end of the war, Rita concluded: “We all survived.”

After more than two decades in the country, in 1955, Baptiste returned with Rita to Europe for the first time to visit his relatives. Her husband’s parents had already passed away. “I think we’re brothers,” one of his brothers told Baptiste. Everything had changed. Baptiste passed away in 1988 at the age of 80, Manuel in 1999, Philip in January 2008, and Gracián seven months later. Joseph Maya died the youngest in 1985.

Rita was honored in August of 2019 at the Basque Cultural Center in South San Francisco on the occasion of her 100th birthday. Rita represents a world that has vanished. She is the living memory of a generation, her parents’ generation, that was forced to leave their homes in search of a better life, like the one they gave her. Both generations established the pillars that sustain the Basque-Navarrese communities of today and the organizations that germinated with them. Away from any self-exclusive ideological conflict that dominates the Basque and Navarrese political panorama, the Basque-Navarrese diaspora in the US lives its multiple and complex identities in an immigrant society with great ease, without questioning the fact of being Basque or Navarrese as incompatible concepts. It is especially this WWII generation that chiseled the contemporary diaspora and helped build a country that would become one of the great super powers on the planet. The debt to them remains unpayable, and that is why it is urgent to make their stories visible. That and no other is the objective of our blog: to bring to light the stories of this generation.

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.