This article originally appeared in Spanish at Euskalkultura.eus on May 27, 2022.

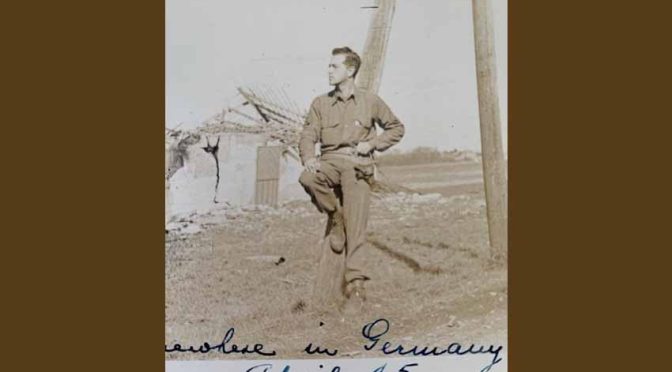

As the Basque-Chilean musician Alberto Arregui contemplated the Statue of Liberty as he entered the Port of New York, the words of Carl Vincent Krogmann, the mayor of the German city of Hamburg, echoed in his head, “Why did you not join us in the salute? Do you not feel sympathy with our cause?” [1]. Alberto — who was fluent in French, German, English and Flemish, in addition to his native Spanish — was working for the Chilean Consulate in Hamburg, when he was forced to flee Germany to save his life [2] .

During a reception organized by the Consulate, Krogmann, who had been invited to the event, gave a speech about the superiority of German culture. The mayor concluded his talk with the usual Nazi salute of “Heil Hitler.” The attendees responded to the greeting by raising their arms. However, Alberto did not. The next morning, two Gestapo men delivered a notice to the Consulate ordering Alberto to leave the country within 24 hours [3]. His time in Nazi Europe had come to an end. On January 20, 1943, Chile broke off relations with the Axis.

From Antwerp to New York via Hamburg

Alberto’s European journey had begun in 1939. Being a tenor, he had come to Europe to continue his music studies. At the university in the Belgian city of Antwerp, he studied for a couple of years, until the invasion of Belgium by Germany — beginning on May 10, 1940 — and their subsequent occupation of the country interrupted his studies. Antwerp was targeted by both the German Luftwaffe from the start of the war as well as by the Allied air forces in their attempt to dissuade Nazi forces from taking control of the city’s strategic port.

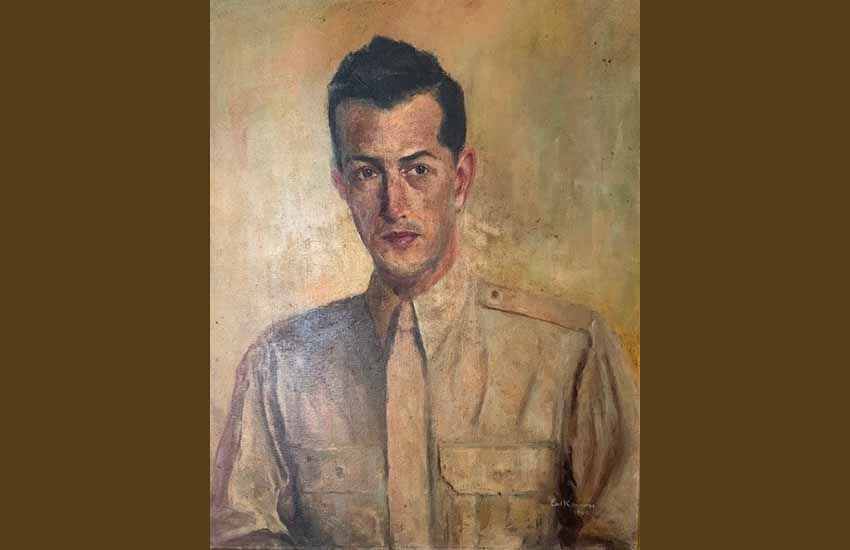

Marita Arregui, Alberto’s daughter, told us about a painting she has in her house that was painted during the war by Emil Kammerer, “a Jewish man whose daughter my father got out of Belgium saying she was his wife. This man gave this to my father in recognition to taking his daughter to Irún.” This act speaks for itself of Alberto’s humanity and courage. Following the invasion, the persecution of Belgian Jews began very early, first by excluding them from economic and public life and then followed by their deportation to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. It is estimated that 25,000 of them were killed [4]. After Antwerp, Alberto had the opportunity to resume his studies, this time in Hamburg, being employed at the Chilean Consulate.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

Stopping Hitler

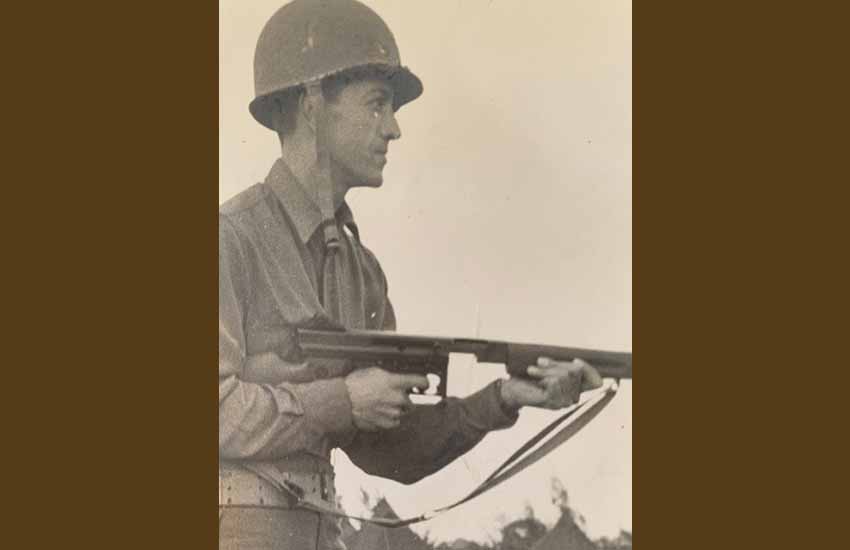

Immediately after landing in New York in September 1943, Alberto headed to the nearest army recruiting center with the sole goal in mind of stopping Adolf Hitler. “A story that reads like that one of the Knights of King Arthur’s Court going to fight in the Crusades is that of Alberto H. Arregui, of Lima, Peru,” wrote Private David A. Bridewell in a November 1943 military newspaper about the man who would become his comrade in arms. “His experiences in Germany and his observation of conditions in Europe,” Bridewell explained, “convinced him that Nazism should be crushed, and he should help the allies by fighting with them” [5].

However, his hope of enlisting was momentarily dashed. The recruiting agent turned him down not only because he was a foreigner but because he was not registered with the Selective Service System, which required at the time that all men between the ages of 21 and 45 register for compulsory military service. “A letter written by the American Embassy in Peru cleared these hurdles for him” [6]. After the draft center, Alberto was sent to a local draft board in New York City. Skipping the times established by the protocols, Alberto even rejected the mandatory three-week leave granted to all recruits to be able to organize their civil affairs before joining military life. He just wanted to join the army. There was no time to lose. Alberto was admitted on September 25, 1943 in New York City. He was 30 years old.

From Gipuzkoa to Peru, passing through Chile

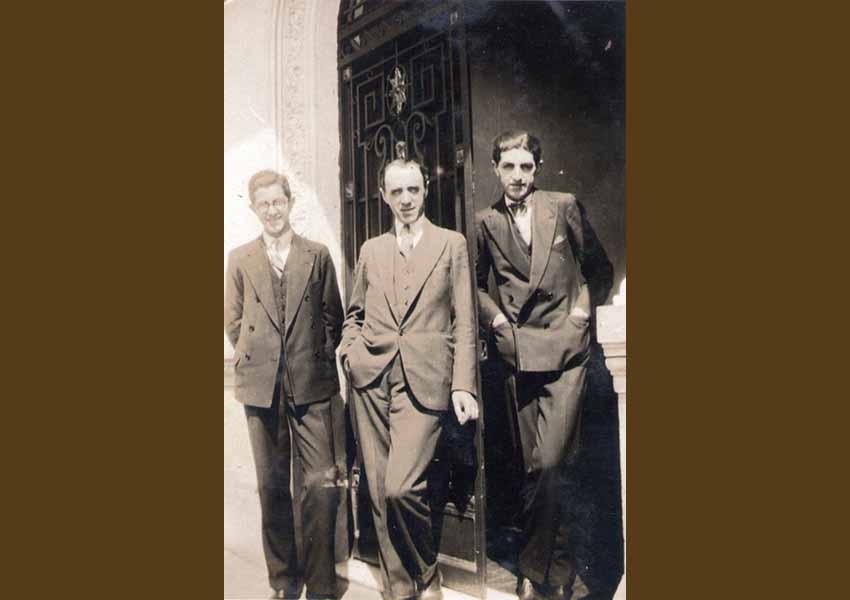

The son of Francisco Arregui Berasaluce and Adela Herrera Heredia, Alberto was born on March 15, 1913 in Santiago de Chile. Francisco, born in 1886 in the Belozaki farmhouse in Mendaro, Gipuzkoa, had emigrated to Chile around 1908, following in the footsteps of his cousins. He made his way via Mendoza, Argentina, crossing the Andes mountain range by the Puente del Inca. “He was very proud of his Basque heritage,” Marita confessed to us. It was a legacy that he faithfully passed on to his descendants.

His mother was born in 1890 in Santa Rosa de Los Andes, Valparaíso, Chile, to a Spanish family settled in Los Andes, San Felipe. It was in Adela’s hometown that Alberto’s parents married in 1910, subsequently establishing their domicile in the country’s capital. Alberto’s siblings were born there: Eduardo in 1911 and Inés in 1919. By that time, Santiago de Chile had become an important destination for Basque emigration. In fact, in 1912 the Basque community in the city had founded the Centro Vasco, which celebrated 110 years of uninterrupted existence this year. In 1915, part of the Basque community of Valparaíso organized the Chilean Basque Center for Mutual Aid [7].

Adela died in 1919 giving birth to Inés, a tragic event that marked Alberto for life. He was six years old at the time, while Eduardo was eight (his father died in 1976, in Lima; Eduardo had died a year earlier). Around 1920 the family moved to Peru, with Alberto and his brother staying in Santiago de Chile, where they were interned at the Colegio de San Ignacio for a few years. Summers were spent in Chillán, in the south of Chile, at the home of relatives. Around 1928, Alberto and his brother moved permanently to Lima, where their father had a felt hat factory, Industrial Sombrerera S.A., founded in 1928. In 1931 he opened another factory, also in Lima, under the name of Arregui y Cía S.A.

Liberating Europe

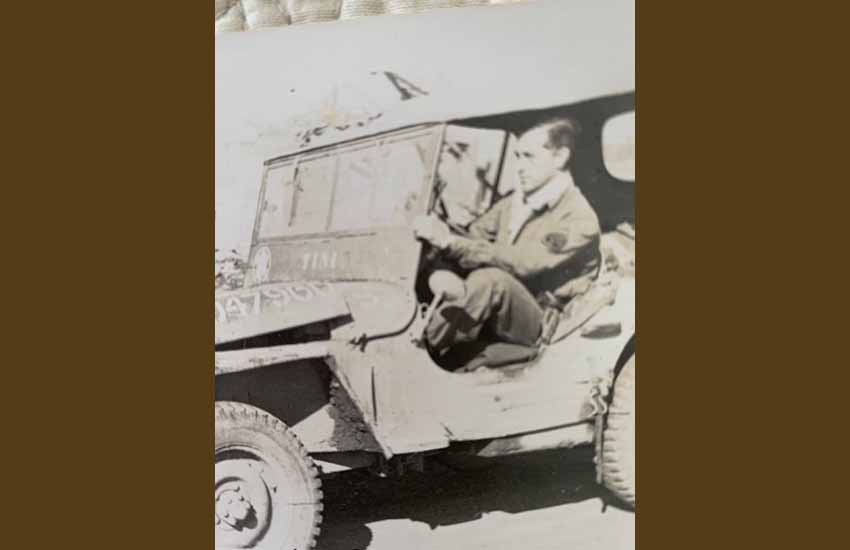

Once enlisted, Alberto was sent from New York to Fort Sill, near Lawton, Oklahoma, for training with the 29th Field Artillery Battalion. He would finally be assigned to Battery B of that battalion.

The 29th Battalion was the main fire support for the 4th Division’s 8th Infantry Regiment since its deployment to the European Theater of Operations. According to the commander of the 29th, Joel T. Thomason, “The battalion with a 15% over strength to cover initial casualties, consisted of about 700 men including 45 officers. The unit was equipped with self-propelled 105 mm howitzers, M-7s” [8]. M105 howitzers were mounted on M7 tracked vehicles. In the words of Irving Smolens, Alberto’s partner in Battery B, “The normal crew for a gun consisted of 12 men. Six men were designated as the “active” crew, and six were designated as ‘reserve.’ Only 3 men were actually needed,” Smolens clarified, “to aim, load, and fire the gun once it was in position” [9].

During World War II, the 29th participated in five major campaigns — Normandy, Northern France, the Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe — in four countries — France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany [10].

Normandy: Landing on D-Day at Utah Beach

“As the darkness gave way to early morning light, I could see a vast armada of boats and ships of all types; it was an awe-inspiring sight. They were so numerous that it appeared one could walk from England to France on them. The atmosphere was electric with excitement and that was my feeling- – one of great excitement. This was the day for which we had trained and awaited so long” [11]. This is how Thomason described the first wave of the H-Hour D-Day assault.

Alberto and his comrades from the 29th Artillery Battalion had arrived in Axminster, England, in January 1944, beginning intense amphibious training at Slapton Sands between February and May. They became the first artillery unit to land on Utah Beach, Normandy, on D-Day. “During the invasion,” Private Smolens explained, “the batteries would fire [high trajectory shells onto the invaded beaches in close support of our infantry] from the deck of the LCT’s [Landing Craft Tanks]. Our M7’s were loaded on the LCT’s two in front, and two in back, each with their ‘active’ crew. The ‘reserve’ crews were located on other boats” [12].

John C. Ausland, liaison officer with the 29th, arrived on the same landing craft as Colonel James Van Fleet, commander of the 8th Infantry Regiment, on the initial assault on Utah Beach. He wrote how “the sound of loud explosions from aircraft bombs and naval shells left no doubt that the beach was an inferno… When the landing craft hit the beach and the front ramp went down, I waded through some shallow water and ran to the shelter of the seawall that ran along the beach – barely glancing at several soldiers who were lying on the sand as though asleep. I could hear rifle and machine-gun fire beyond the dunes, and some mortar shells fell not too far away” [13]. Ausland’s mission on the ground was to guide the 29th’s three artillery batteries into firing positions. However, he soon learned from Thomason that one of the batteries had been destroyed.

During the first hours of the invasion, the 29th lost an entire gun battery when the landing craft (LCT-5) carrying it collided with an enemy mine floating a mile offshore. This was the assault element of Battery B, which consisted of four howitzers. It sank almost immediately. This was reported by Peter N. Russo, a witness to that event, and at that time a member of Battery C; later when Battery B was reformed, Russo would be transferred to the new Battery B, as crew chief of the number one artillery piece.

“Daylight was now approaching and the volume of planes flying overhead was noticed. Bombs were landing on the beach, in hopes of destroying enemy guns emplacements. The Navy guns joined in pelting the same area. […] Our attention was diverted by a large boom to our left flank and not more than 50 feet to our center. The boom was followed by a huge puff of smoke. B Battery was leading the Battalion Artillery toward the landing site on Normandy. It struck a mine in the water and was gone. We could see very little debris and a few bodies as we rode by. All on our landing craft tanks were up and looking at what was left of B Battery personnel, the landing craft and the equipment. Sea sickness was replaced with horror and fear. We were introduced to our first combat exposure. We focused on the enemy artillery rippling along our landing zone and thought about the losses to be added to that of B Battery. […] Not a sound was to be heard on this craft until we landed. We became seasoned veterans before one round was fired in support of our Infantry” [14].

As described by John K. Lester, another member of Battery B and a Jeep driver for a forward observation party, “When I reached the beach on another landing craft and learned of the loss, I was devastated. How quickly I lost so many good friends and buddies. What a way to enter into conflict. The rest of that day draws a blank. I can’t recall much of anything. […] We didn’t know what was happening. Everything was very confused” [15].

A total of 59 officers and soldiers were wounded, with 39 killed. The remaining 20 were seriously injured to such an extent that only 3 or 4 were able to return to active duty and rejoin their comrades months later. The 29th “had lost one-third of its firepower before we even entered combat… That was a great tragedy,” Thomason stated [16]. The reason Alberto and the rest of his mates from Battery B, including Smolens, survived was that they were not ‘active’ personnel and were held in reserve on another ship. In the late afternoon, towards nightfall, Alberto and the remaining men of Battery B were transported to the beach. They had been very lucky. As Thomason noted, “Of the 28,000 men landed on Utah Beach on D-Day, the total casualties were remarkably light — just under 200. Unfortunately about one-third of that number came from one small artillery battalion — the 29th Field Artillery Battalion” [17]. The 29th was awarded the Presidential Citation for their part on D-Day in Normandy on June 6, 1944.

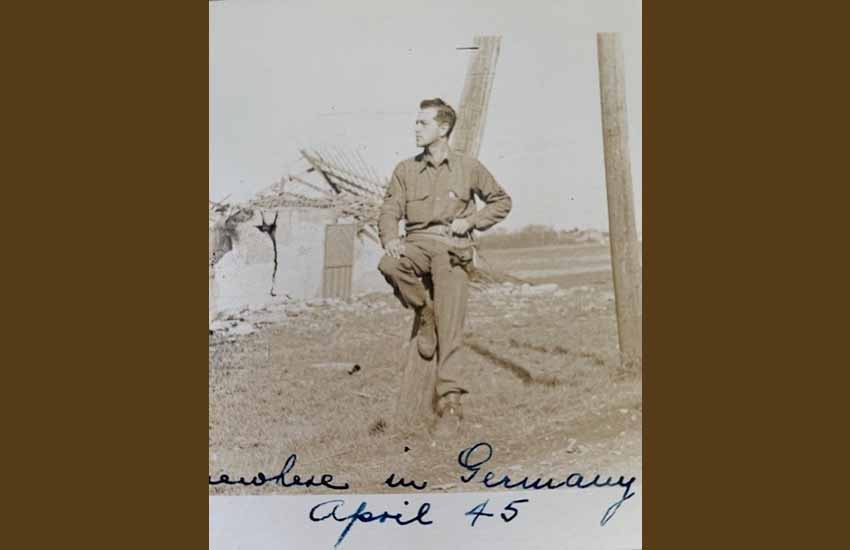

From the Liberation of Paris to Victory in Europe Day, May 8, 1945

As its main fire support unit, the 29th Artillery Battalion continued to support the 8th Infantry Regiment during 11 months of combat in continental Europe, taking part in the capture of Cherbourg, the drive towards St. Lo., the liberation of Paris and Belgium, at the entry into Germany in September 1944, at the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, at the crossing of the Rhine River in March 1945, and at the end of the war in Bavaria in May 1945. Due to the fierce fight carried out in the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest by the 29th, they were baptized by the Wehrmacht as “The beasts of the Hürtgen Forest.” Right at the beginning of this battle, the Basque-New Yorker Julián Oleaga, a soldier from Company B of the 1st Battalion of the 18th Regiment of the mythical 1st Infantry Division, the “Big Red One,” was wounded in combat on the outskirts of the city Aachen on September 18, 1944, for which he received the Purple Heart. Almost a year after his desperate flight from Nazi Europe, Alberto returned to Belgium and Germany, this time as a liberator.

The 29th Battalion also contributed its support to the French 2nd Armored Division in the liberation of Paris. “I was with the first Americans in Paris on August 25, 1944,” enthused Lester, a soldier from Battery B. “That was a most exciting day” [18]. According to his companion Smolens, “We were then designated as the division to liberate Paris, along with the 2nd French Armored Division. Our forward units, according to infantrymen with whom I have spoken, could have entered the city before the French, but were told to wait for the French. We penetrated to the heart of the city, around Notre Dame, the Place de La Concorde, the Hotel de Ville, and the notorious Police Headquarters. We were denied the honor of parading down the Champs Elysee. Our job was chasing Germans across the Seine River and Belgium, and into Germany” [19].

The 29th Artillery Battalion fired a total of 182,000 rounds of ammunition at the enemy in Europe. The 4th Division returned to the United States in July 1945 to prepare for the invasion of Japan. However, the war ended before the invasion could take place [20]. Alberto and his companions were repatriated and Battery B was deactivated on February 14, 1946 at Camp Butter, North Carolina.

Alberto was discharged with honors with the rank of technical sergeant. Like all veterans of the US Armed Forces honorably discharged in World War II, Alberto also received a letter of recognition signed by President Harry S Truman [21].

“My father,” confessed Alberto’s daughter to us, “was very reserved specially when it came to the war and what happened during those years.” The testimonies of his comrades from Battery B that we have collected here speak for the silences that drowned Alberto’s voice for much of his life and faithfully convey to us the sensations of the first moments of the invasion of Normandy and the liberation of Paris.

Alberto received the American Defense Medal, the American Theater Medal, the European Theater of Operations ribbon with bronze arrowhead and five campaign stars, the German Army of Occupation Medal with clasp, the Presidential Citation, the Belgian War Cross, and the World War II Victory Medal. Despite his service to the country, he never obtained US citizenship.

He more than fulfilled the mission that prompted him to travel to New York for the first time. It was time to go home. Hamburg mayor Krogmann was arrested and interned in Bielefeld, Germany; he was fined 10,000 marks in August 1948 for belonging to a criminal organization. He was subsequently released. He passed away in 1978, at the age of 89.

From the United States to Lima, Peru

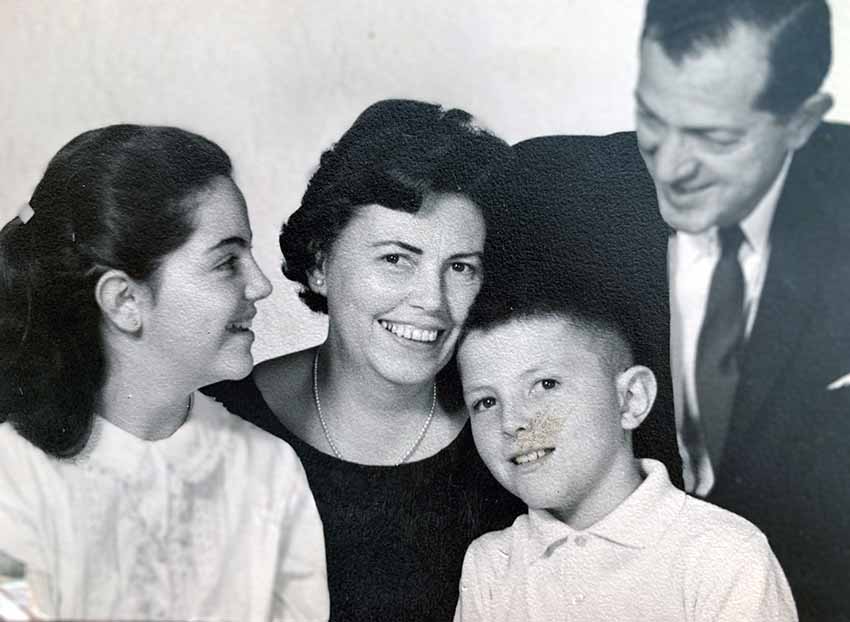

Upon his return to Lima, Alberto joined the family business. Unfortunately, his musical career was over. He became a Peruvian citizen after the war when he started working in the factory. In 1946 he met his future wife, La Vern Betty De Ny (born 1920 in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, died 1995, in Lima) while she was visiting an uncle of hers who worked for City Bank in Lima.

They married in 1949 in La Vern’s hometown, establishing their residence in Lima. They had two children during their marriage: Francisco (Lima, 1951-2007) and Marita. Alberto directed the two family factories until his retirement.

Alberto died in 1980 at the Clinica Anglo Americana in Lima, at the age of 67. In 2016, his sister Inés passed away, the last person of the first generation of the Arregui family born in Chile.

“Unfortunately, many things went unsaid and now more than ever I wish they would have been answered,” concludes Marita. “My father was a very extraordinary person, but two events marked his life. His mother’s premature death and the war. It’s not only fighting during the war but living a life after having taken part in it and live along side with the burdens and nightmares of a war. I always felt there were two Alberto Arregui, one covering up the other,” she asserts.

Just after the 77th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe, in a context marked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we want to remember all those men and women whose sacrifice made it possible to liberate Europe from the clutches of Nazi totalitarianism, and very particularly of those of Basque origin like Alberto, who, from different countries of the Basque diaspora, whether they were Argentina, Chile, Cuba, the Philippines, Mexico or Uruguay, joined the allied forces.

References

[1, 3, 5, 6] Bridewell, David Alexander. “Modern ‘Knight’ trains for his crusade after arguing way into Army”. (November 5, 1943). Bridewell (Forrest City, Arkansas, 1909-1999, Winnetka, Illinois) served in Battery B of the 29th Field Artillery Battalion and as a captain in the United States Army Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps.

[2] In 1940, Miguel Cruchaga Ossa was appointed Consul General of Hamburg. He was replaced by Eugenio Palacios Bate on November 18, 1940. (Archivo General Histórico del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores del Gobierno de Chile (https://www.minrel.gob.cl/ministerio/archivo-general-historico); (https://www.archives.gov/iwg/research-papers/breitman-chilean-diplomats.html).

[4] “Antwerp commemorates World War II”

[7] Oiarzabal, Pedro J. (2012). “En nuestro propio mundo”. Basque Identity 2.0., EITB

[8, 11, 16, 17, 20] Thomason, Joel T. (April 30, 1994). “The 29th Field Artillery”. Thomason was appointed commander of the 29th Battalion on September 1, 1942, at the age of 24. On June 12, 1944, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

[9, 12] Smolens, Irving. “Reflections of a crew member”

[10] “29th Field Artillery Regimental History”; and Smolens, Irving. “29th Artillery Battalion played big role in Fourth Div. actions.” USTS Hermitage Newspaper. (July 1945)

[13] Ausland, John C. “A soldier remembers Utah Beach.” The International Herald Tribune. (June 6, 1984). He is the author of “Letters home: A war memoir” (1993).

[14] Russo, Peter N. “The Great Pinochle Game!”

[15, 18] Lester, John K. “I served with the 4th Infantry Division during World War II”

[19] Smolens, Irving. “B Bty, 29th FA Battalion. D-Day and Beyond…!”

[21] Harry S Truman had also been trained in the Field Artillery at Fort Sill, commanding Company D of the 129th Field Artillery during the World War I.

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”