John Ysursa is near-omnipresent in the Basque community of the United States. He’s seemingly at every festival, he’s a central part of Boise State University’s Basque program, and he has authored a book on Basque dance. His enthusiasm for all things Basque – particularly how to get others excited about the Basque culture – is infectious. A few years ago, I had the pleasure of hearing him speak about how we can make being Basque cool for the next generation. I had so many questions… it’s taken a while, but I’m happy to present this interview with John.

Buber’s Basque Page: Let’s start with a bit of introduction. Who is John Ysursa? What is your backstory, or your Basque story, if you will?

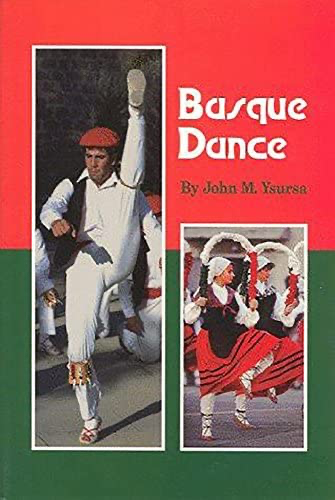

Photo from Boise State University.

John Ysursa: I was born in Boise, Idaho to Basque parents: Ramon Ysursa and Begonia Ormaetxea. My youth was very much connected to Basque identity and I followed a common path shared by other American born Basques: hearing different languages at home (Spanish and Basque); a world of friends populated by Basques, going to learn Basque folk dance at age seven, etc. Oh and our school lunches were always a bit different from the other kids 😉

BBP: In your recent talk Got Basque? you discussed Basque identity in the United States. In particular, you described how identity is more and more a choice, particularly for the grand and great-grandchildren of those original Basque immigrants. How do we make being Basque “cool” so that they choose that as part of who they are?

John Ysursa: It’s one thing being born and raised Basque and another to decide as you get older to want to remain connected to this as a thick (vs. thin) identity; i.e., choosing to make being Basque a bigger rather than smaller part of one’s identity. In my case though I heard it often, I didn’t really know much Euskara/Basque at all beyond some words and phrases; I couldn’t really speak it. So I learned the language as an adult. It was a choice therefore to connect with one of the key elements of Basque identity–the language Euskara which is how historically Basques identified themselves since the name for themselves isn’t Basque/Vasco (which derive later from French and Spanish) but Euskaldunak which means those who speak Basque. Note that this is not to say if someone doesn’t speak Basque that they are not Basque: there are many ways of making being Basque a thick identity. It can be Basque dance, Basque sports, playing the card game mus, Basque music, Basque food, etc.

The reference to “cool” derives from the ever elusive element we all sought as teenagers. In the Basque case, it came from a friend saying to you “aren’t you Basque?” When you replied yes they responded gushing “that’s cool because I went to a Basque festival and it was great!” Bingo. Right there the teenager had a part of his/her identity validated and being Basque was cool. Basque culture affords those kinds of moments in different ways, and not just for the parties. Many are struck, for example, by the multi-generational aspect of Basque gatherings in a society such as ours that is regimented by age; i.e., many hang out with only people their own age. Basque culture demonstrates connection with something quite old and that’s striking to most Americans where things here are relatively much younger.

BBP: Was there a particular point in your life which made you decide that you wanted a “thicker” Basque identity? And how has your choice impacted your life beyond being Basque?

John Ysursa: I think my story follows that of many other young people, who when given some responsibility, take on a greater degree of ownership and interest. For me it was my senior year in high school when I was elected the boy’s dance director for the Boise Oinkari Basque Dancers. That set in motion about three decades of involvement with formal Basque dancing.

BBP: Related to that, without the influx of immigrants, we are in danger of losing any real connection to the Basque Country. The elements that we emphasize here, such as dance and music, are relatively small components of Basque identity over there. How do we keep Basque culture in the United States from becoming purely folkloric?

John Ysursa: Basque migration to the United States slowed to a trickle in the 1970s. Today many Basques come over but as tourists or students and they return. No doubt that changes things for the Basque community here, but there are ways to compensate for this broken connection (migration) with others (internet). A game-changer has been the explosion of virtual Basque communities in cyberspace, as illustrated by buber.net. And the Basques who come here for a time also serve as a great infusion of energy. As to the point of a folkloric Basque identity, this is pronounced throughout the Basque Diaspora (those who live outside the Basque Country but identify as Basque). It’s fine actually as long as it doesn’t get locked into a single understanding of being Basque. We get plenty of the “new” from our everyday modern culture, so this can keep us rooted and connected to something much older. And some of that new is brought to us by the visiting Basque friends. So we can meld the old and the new.

BBP: Are there elements of the modern Basque Country that you find particularly interesting, that you try to incorporate in your own personal Basque identity?

John Ysursa: I know I’m not alone is seeing the Basque Country as a great place. I was born in Idaho, but had a chance as an adult in 1983 to go live in the Basque Country for six months, courtesy of an invitation from the Bieter family. Initially I wasn’t too keen on learning Euskara the Basque language. I spoke some Spanish and considered it was enough. But it was my time in Onati, meeting the people there, that I came to realize that if I really wanted to know Basque people, I had to learn Basque. That’s been the biggest element that I incorporated into my Basque identity–to become Euskalduna (“One who speaks Basque”).

BBP: You described specific elements that tended to define the identity of the United States Basque. I was struck by the generally conservative tilt those elements have, which makes sense given the type of work that brought many of those original immigrants to the US west. At the same time, it seems that the Basque Country is, if anything, going the other way: more urban, less religious, generally more liberal in many ways. Do you see this as an extra challenge in keeping Basque identity in the US connected to the Basque Country of today, that the gulf will widen even more?

John Ysursa: I’m not making the case here to be a modern Conservative or Progressive: I want to stay away from that cat-fight. It shouldn’t be too controversial to acknowledge, however, that most Basque immigrants brought with them a conservative mindset that included elements such as emphasis on family and community, religion, work ethic, perseverance, a rural outlook, etc. There’s no doubt how quickly things have shifted in a couple of generations. Interestingly, in a good many of our Basque clubs politics has been forbidden–sometimes formally. Most recognized how political differences could quickly erode unity, so the formal and informal prohibitions have largely been successful. Most are willing to suspend discussions about current politics and focus instead on renewing friendships. It works!

BBP: Fair enough! I also don’t want to wade into a controversial subject. But, let me ask my question in a slightly different way. Basque-American culture is overwhelmingly rural while life in today’s Basque Country is, in large part, urban, though of course with rural elements. Do you see this difference as leading to new challenges in each side relating with the other? Do we at some point drift far enough apart that we have little in common?

John Ysursa: Just a bit ago (July 2022) there was a visiting Basque Country artist who was interviewed about her time here in Boise. One thing she noted was surprise in how she saw the Boise Basque community almost stuck in time. She commented how we were still dancing like our grandparents, but this was not complimentary but more critical that Basques here were stuck in the rural context. The observation is spot on. While many of our grandfathers were involved in the sheep industry, today hardly any Basques remain. Yet here we celebrate the sheepherder legacy. In a similar fashion (though not the same since sheepherding was more of a dynamic for the American West but not New York City which is our oldest US club), most all the Basque communities of the Basque Diaspora (those who live outside the Basque Country but still consider themselves Basque) celebrate our legacy. That doesn’t mean that modern elements aren’t present, but that’s not our primary focus. The artist made the case of how in the Basque Country their Basque culture was largely modernizing. True enough. But the context is very different for most of us here in the Diaspora. Our society is overflowing with the new, modern, innovating, etc. That metaphorical cup is full. In contrast, we find in Basque culture something of permamence and endurance. We crave the old because in this country we’ve got plenty of the new.

BBP: Your wife also has Basque roots. What steps, if any, have you and her taken to instill a sense of Basque identity to your children? How have you balanced the desire to pass something along without forcing something they may not (yet) appreciate?

John Ysursa: While we raised our two boys in a Basque context, and they danced and attended Udaleku, went to the Basque Country, etc. But now that they are young adults in their early 20s, the jury is still out how much or how little they’ll “be” Basque.

Very interesting article. Being full Basque, I have always felt it important to pass my heritage on to my sons, grandchildren, & they to their children.

Greetings Margaret–What is full Basque? Were you born and raised in the European Basque?

It is important for children to know where their parents come from.

Monique

Thanks for sharing

Wonderful article Blas!

The language, in my opinion, is the spirit of any nation. In my domain I am teaching my granddaughter as much as possible.

Greetings, Joseba,

You are right, language is the spirit and I would add the soul of a nation. Good for you!!

Monique

That Y guy sure is smart.

Greetings, Interesting article! Mr. Ysursa is diplomatic and lucid.

I do not believe that there is a gulf between the American Basque culture and the European, French and Spanish, Basque. They are both different and have their own merit. Ditto for the Basques in Argentine or other south American country or anywhere in the world.

Paz a los que llegan, Salud a los que quedan, Felicitades a los que marchan. From my favorite Basque province..Alava.

Monique