This article original appeared in Spanish at EuskalNews.eus.

By Pedro J. Oiarzabal and Guillermo Tabernilla

“He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 1888).

Operation Rainbow 5

Pedro J. Oiarzabal and Guillermo Tabernilla are the principal investigators of the research project “Fighting Basques: Basque Memory of World War II” of the Sancho de Beurko Elkartea in collaboration with the North American Basque Organizations (NABO). The present article derives from the “Fighting Basques” project.

Oiarzabal received his Doctorate of Political Science-Basque Studies from the University of Nevada, Reno. Over the last two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is a member of Eusko Ikaskuntza.

Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Elkartea, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques of both slopes of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government. He is author, along with Ander González, of Basque Fighters in World War II (Desperta Ferro, 2018).

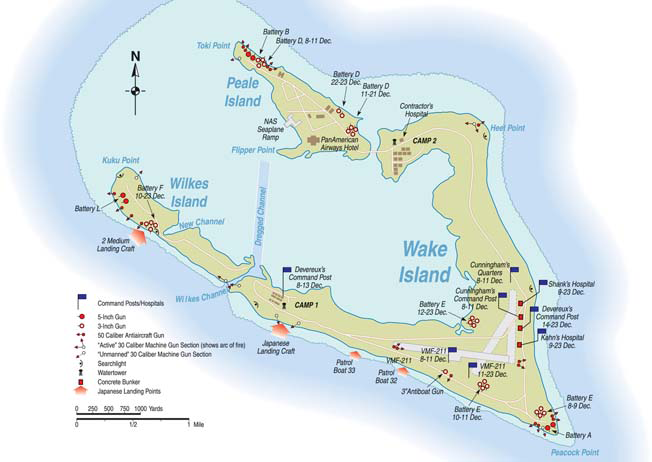

The escalation of tensions between Japan and the United States during the 1930s focused attention on the Pacific Ocean, primarily on the weak defense of the Hawaiian Islands against a potential enemy attack. The US government designed “Operation Rainbow 5” with the objective of defending the west and southwestern flank of Hawaii, through the construction of military bases on five islands: Wake, Midway, Johnston, Palmyra, and Samoa. However, the plan came too late.

In January 1941, a consortium of civilian firms called the Pacific Naval Air Base Contractors began construction of US military installations on Wake Island. Located in the western part of the Pacific Ocean, Wake, with two small islets (Peale and Wilkes), is considered one of the most isolated islands in the world. It is located 3,700 km (2,300 miles) west of Honolulu, Hawaii, and about 3,200 km (1988 miles) from Tokyo, Japan. It was formally claimed by the US in 1899 as a strategic atoll (uninhabited at the time) for maritime, military, and merchant refueling.

Source: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/Wake/maps/USMC-M-Wake-0.gif

One of the primary construction companies, if not the most important one, in Wake was the Morrison-Knudsen Civil Engineering Company, based in the then small town of Boise, Idaho. At the time, Boise had about 26,000 inhabitants and a significant population of Basque origin, which had been growing since the last third of the 19th century. In August 1941, the first military garrison was permanently established on the island, consisting of 399 Marines from the 1st Defense Battalion, 50 from the Marine Corps Combat Squad (VMF-211), 68 from the Navy, and 5 from the Army.

and Richard Pagoaga. (Courtesy of the Pagoaga family).

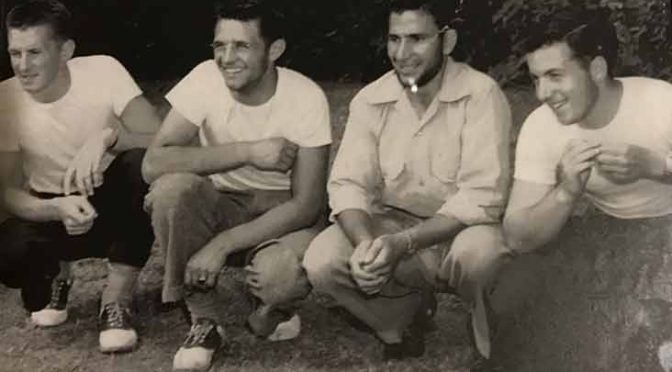

By December, the consortium had more than 1,100 construction workers in Wake. About 230 came from Idaho. Among them were seven young Basque-Americans: George Joseph Acordagoitia, Ignacio Frank Arambarri, Joseph Goicoechea, Angel Madarieta, Joseph Mendiola, Richard Joseph Pagoaga, and Robert Lemoyne Yriberry. All of them had parents from Bizkaia, with the exception of Pagoaga, whose father was Gipuzkoan and whose mother was born in Boise (herself of Bizkaian parents), and Yriberry, whose father was from Lapurdi and whose mother was American. The Basque parents had arrived in the country between 1899 and 1920, although most had done so during the first decade of the 20th century. For their children, the $120 a month plus room and board offered to go to Wake were more than attractive incentives for younger workers. At that time, good jobs were scarce; add to that their desire for adventure and to know the world, and the opportunity was irresistible. “For young people, it was paradise,” recalled Joseph Goicoechea Zatica [1]. Born in Jordan Valley, Oregon, in 1921, he was 20 years old at the time. Goicoechea, with a group of his best friends including George Rosandick, Murray Kidd, and Richard Pagoaga Yribar who was born in Boise in 1922, decided to try their luck and apply for the job for Wake, an island they had never heard of before, as they would confess years later. At 19, Pagoaga was the youngest of Wake’s Basque-Americans. Soon that paradise turned into a nightmare.

The Battle of Wake

The Empire of the Rising Sun launched a simultaneous attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (on December 7), and the then almost unknown Wake, during noon local time on December 8 (note that Wake is west of the International Date Line). Pearl Harbor had been attacked five hours before Wake. The Japanese bombers came from the Kwajalein bases in the Marshall Islands. The attack on Pearl Harbor was the trigger that caused the US to enter fully into World War II.

Source: http://maximietteita.blogspot.com/2017/01/battle-of-wake-island.html

After the first air raids, more than 185 workers volunteered to fight alongside the Marines, and about 250 other workers helped them with other tasks. Goicoechea was recruited in the heat of battle. He had military training and experience. He had participated in the Reserve Officer Training Corps, and, being a minor at 17 years old, after forging his father’s signature he enlisted in the 116th Cavalry Company of the Idaho National Guard. Goicoechea was seriously wounded in the first Japanese attacks. Even so, he continued to help the Marines constantly move artillery pieces to avoid being hit by shelling. He was only 20 years old. “I was frightened; you never get over it […] The first night was the worst night in my life. I was shaking and didn´t know what the heck was happening. You could see the older men were just as scared as you were. I used to hear a lot of guys pray,” Goicoechea would recall years later [2].

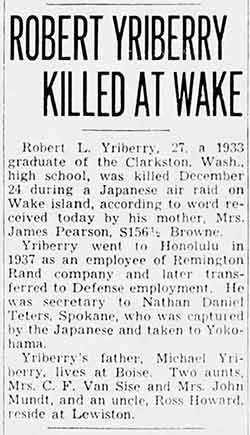

The oldest of Wake’s Basque-Americans, Robert Yriberry Howard was not so lucky. Born in Council, Idaho, in 1914, he dedicated his life to construction. From 1937 he worked in Honolulu for the Remington Rand Company, later transferring to the Pacific Naval Air Base Contractors consortium. Yriberry was the first Basque to arrive on the island, in October 1940. He was the “valuable” secretary of Morrison-Knudsen’s general superintendent, Nathan Daniel Teters, in charge of the Wake workers, who would also be captured like the rest of the island’s inhabitants. Yriberry died on December 9, 1941, at the age of 27, during an air raid that deliberately destroyed the hospital where he was staying, having “received shrapnel wounds in the first attack” [3]. Yriberry is buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, in Honolulu. He is probably one of the first, if not the first, Basque-American fatality (either civilian or military) of World War II.

The first invasion attempt by Japanese troops occurred on December 11, though it was successfully repelled by the few American forces. It was the first amphibious attack on a territory under US control during WWII. The first such attack on US territory would take place in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska six months later, and in which there was significant Basque-American participation.

Meanwhile, between December 8 and 10, Japan had occupied the Philippines, Guam, and the Gilbert Islands, taking 400 construction workers on Guam prisoner. Operation Rainbow 5 had failed. Among those captured in Guam was the Bishop of the Capuchin Order of Nafarroa, Miguel Ángel Urteaga Olano – “León de Alzo” – head of the Catholic Church on the island since 1934. Born on September 29, 1891 in Altzo, Gipuzkoa, he had arrived on Guam in 1918. Like the rest of the prisoners, he was sent to Japan on January 10, 1942. However, he was released under the protection of the Government of Spain and resided first with the Spanish Jesuits in Tokyo and later traveled to Goa and Bombay, returning to Guam, after its liberation, on March 21, 1945. Sent to Manila, he retired in 1960 in San Sebastián-Donostia. He passed away on May 21, 1970, during his last visit to Guam, where he was buried [4].

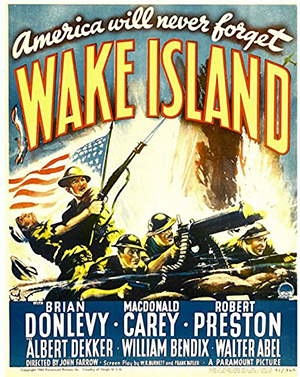

The next landing at Wake was on December 23, and it was impossible to stop it. Wake was cut off by air and sea and was unable to receive soldiers or supplies to repel the invasion. The defenders, under the command of Major James Patrick Sinnot Devereaux, eventually capitulated and the island was occupied. An epic new chapter in American history had been written, the defenders even being compared to those who held out to the end at the Alamo [5]. Unlike the battle in Texas, 105 years earlier, there were survivors, but as we will see, their destinations would become a true purgatory. In the face of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the defense of Wake was an injection of morale for the despondent American society. It became the first military setback for the Imperial Japanese Navy in whose plans the capture of a small atoll in the middle of the Pacific should not have proven to be any problem. Quickly, the Hollywood film machine went to work on what would become the first WWII combat film by Paramount, with a clear propagandist profile. On August 11, 1942, director John Farrow‘s Wake Island opened at the Marine Corps base in San Diego, California. Meanwhile, the whereabouts of the survivors of the Battle of Wake remained unknown to the general public.

The Japanese had lost some 1,000 soldiers in combat, and more than 300 were wounded. The defenders lost a hundred soldiers and civilians, including Americans and Guamanians – workers for the Pan American Airways company, which had built a small town with a hotel. The Japanese subsequently garrisoned more than 4,000 soldiers on the island and erected large fortifications to protect them from any retaliation for the occupation.

All but 98 skilled workers were evacuated from Wake. These 98 remained on the island to operate the necessary machinery in their eagerness to fortify it. However, the American response was not to recover the island, but rather to block it, causing a lack of supplies and starvation among the Japanese troops. Beginning in February 1942, constant and intense air and sea bombardments, the first and most important in the Pacific War, were added to the American effort. Between October 5 and 7, 1943, the Japanese bases at Wake were totally destroyed by the largest concentration of American aircraft carriers in the history of naval warfare. Aviation Lieutenant Pablo “Paul” Bilbao Bengoechea, born in 1917 in Boise to Bizkaian parents, was on board the USS Lexington, one of the aircraft carriers participating in the attack. The military onslaught had unforeseeable consequences. Faced with what the Japanese thought was an imminent invasion, they executed the 98 Americans on the 7th.

To be continued…

References

[1] Garber, Virginia S. “Survivors remember Wake Island”. The Times-News (Twin Falls, Idaho, September 17, 1995, page 9).

[2] Cited in Wukovits, John (2003). Pacific Alamo: The Battle for Wake Island. New Amer Library.

[3] Gilbert, Bonita. (2012). Building for War: The Epic Saga of the Civilian Contractors and Marines of Wake Island in World War II. Casemate Editor. Page 215.

[4] Sinajaña, Eric (2001). Historia de la Misión de Guam de los Capuchinos Españoles.Pamplona: Curia Provincial de Capuchinos.

[5] See, for example, Wukovits, John (2003). Pacific Alamo: The Battle for Wake Island. New Amer Library.

Quoting Nietzsche!! is this is why this Fighting Basque Project is about? To inspire young Basque people, on both side of the Atlantic, to joyously go to battle even if they get blown to hell for this discombobulated idea that absolute freedom is real.

Surely Oiarzabal andTabenilla must know that Nietzsche’s ideas were used and interpretated by the nazi’s to justify their atrocities.

Before doing anything senseless, talk to you mother!

Monique

My father, George Rosandick, was the son of Croatian immigrants. I grew up around the Wake Island “crew”. They were the best of friends before the war, and even better after. All of them were captured on Wake and imprisoned during the war. Remarkably, they all survived the very cruel treatment by the Japanese. Idaho’s Senator Frank Church recognized their contributions to the war effort and championed their award of Veterans Benefits.

the more reason to work toward peace rather than war!!! Does anyone know of a country that has not at one time or another committed unspeakable cruelty. Do you? did you fight in war? Even if you were not old enough to fight in a war, do you know what war is like? did any one come to your door begging your parents to take their children for safety and to feed them. How would you feel if you were that child–to be left with stranger who, in some cases, did not speak the same language as you did. While picking wild berries, did you come up a terrible smell, took few steps–there was the body of a soldier, clutching in his hand the photo of a woman holding a young child??

The crew of the ” wake” deserved all the benefits they could get and more!!!!

Croatia!! Honor and respect your grandfather.

Monique