This article original appeared in Spanish at EuskalNews.eus.

You can find Part I here.

By Pedro J. Oiarzabal and Guillermo Tabernilla

The Evacuation of Wake

After the Japanese occupation of Wake Island on December 23, 1941, both military personnel and civilians were made prisoners of war without distinction, beginning an inhumane treatment that would continue throughout the war. Joseph Goicoechea Zatica‘s son, Dan, recalls how his father “was beaten so badly with a rifle butt that his eye came out of his head […] (He) bled from his eyes and ears and no one could believe he was alive” [1]. Against all odds he survived.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal and Guillermo Tabernilla are the principal investigators of the research project “Fighting Basques: Basque Memory of World War II” of the Sancho de Beurko Elkartea in collaboration with the North American Basque Organizations (NABO). The present article derives from the “Fighting Basques” project.

Oiarzabal received his Doctorate of Political Science-Basque Studies from the University of Nevada, Reno. Over the last two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is a member of Eusko Ikaskuntza.

Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Elkartea, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques of both slopes of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government. He is author, along with Ander González, of Basque Fighters in World War II (Desperta Ferro, 2018).

The prisoners were transferred to the merchant ship Nitta Maru on January 12, 1942. The cruelty was not long in coming. On board, the Japanese tortured, executed, and dismembered several American marines. The ship continued its course to Yokohama, Japan, and from there to the Woosung POW Camp, a suburban area in Shanghai, China. Sadly, they were among the first American prisoners of war (military and civilian) of WWII, and among these were our Basque protagonists. The families did not hear from them for years. For example, the family of George Acordagoitia Mallea, born in 1918 in Jordan Valley, Oregon, received his first letter in January 1945, stating that he was in good health. (Perhaps it is necessary to mention that the letters had to pass the filter of the Japanese censors.) The letter was dated August 2, 1944. Similarly, the family of Joseph (Laucirica) Mendiola, born in Ogden, Utah in 1917, was given a first letter in May 1945. The letter was dated September 10, 1944, and in it Mendiola wrote, “I am all right and very hopeful of returning some day” [2].

The anguish of the families and in the Boise Basque community was evident. Goicoechea’s mother, Eladia Zatica Uriate (born in Ispaster in 1891), began a daily barefoot pilgrimage, carrying a lighted candle from her home to a small Catholic church in downtown Boise for mass at 5 in the morning. According to her grandson Dan Goicoechea, “She knew if the candle didn’t go out, he was alive,” Dan said. ‘Don’t tell me my son’s dead,’ she’d tell people. ‘A mom knows when her son is dead.'” [3].

Prisoners in camps in China and Japan

(The Times-News. Twin Falls, Idaho, September 23, 1945).

In December 1942, the Wake survivors were transferred to another Shanghai POW camp, at Kiangwan. They spent a chilling winter in tropical clothing, and in the case of some like Goicoechea, without shoes. In August 1943, more than 500 men were sent to Japan and forced to work for the Japanese war effort. Ignacio Arambarri Alberdi, born in 1917 in Gooding, Idaho, was 24 years old when he was taken prisoner. He was sent to the Fukuoka-Kashii coal mine, on the Japanese island of Kyushu, which had been converted into a prison camp. On December 20, 1943, the US Department of the Army in Washington officially notified Arambarri’s mother of his whereabouts in Japan. There he was forced to work ten hours a day, under mistreatment by his captors, until his liberation on October 15, 1945, by American troops.

In Fukuoka-Kashii, Arambarri coincided with the corporal of the 31st Infantry Regiment Manuel Eneriz Arista, born in Santa Clara, California, in 1920, to a father from Nafarroa and an Andalusian mother. Eneriz had been taken prisoner during the Japanese invasion of the Philippines and, having survived the infamous “Bataan Death March,” he was sent to Japan. During their captivity, at a distance of 48 kilometers away from Nagasaki, Arambarri and Eneriz witnessed how the atomic bomb hit the city on August 9, 1945. Eneriz died in 2001, at the age of 81 in Camarillo, California. .

Most of the remaining POWs stayed for three years in various POW camps in Shanghai. Among them were Mendiola and Angel Madarieta Osa, born in Boise in 1921. He was only 20 years old when he was taken prisoner on the island.

(The Times-News. Twin Falls, Idaho, November 10, 2001. P. 6).

Acordagoitia and Joseph Pagoaga Yribar were interned together in the main camp in Osaka, Japan (also known as Chikko, Osaka 34-135) until its destruction on June 1, 1945 in a firebombing raid by American B-29 super-flying fortresses. Acordagoitia and Pagoaga, together with the rest of the prisoners, were then transferred to the Tsumori camp and from there to Kita-Fukuzaki. In the port of Osaka they did forced labor, loading and unloading ships.

The last prison camp in which Goicoechea was held was Camp Area 1 (Kawasaki), in the Tokyo Bay area. At the end of the captivity, according to his son Dan’s account, his father’s leg received a sword cut and became infected. “One of the Japanese doctors smuggled sulfa drugs to my Dad to try to keep him alive.” Meanwhile, other prisoners stole food to share with Goicoechea. The Japanese found out. “My Dad was beaten for three days and never gave their names up” [4]. Goicoechea was repatriated after 46 months of captivity via the Philippines. He received the Purple Heart for injuries received during the fight on Wake Island.

The total time of incarceration for the Wake prisoners was 44–46 months (3 years and 6–8 months). Madarieta, for example, was held captive for 44 months and Mendiola was repatriated in September 1945. He received medical attention at the fleet hospital in Guam on his way home via San Francisco, California in October 1945.

Wake prisoners were brutally beaten, starved, tortured, and forced to do slave labor within Japan’s factories and war industries. Many died of dysentery and malaria, among other diseases. An estimated 250 of the more than 1,000 civilian employees died on transport ships or in forced labor camps.

War veterans

Four years later, fate would drastically change his life.

Wake remained under Japanese possession until September 4, 1945, two days after the Japanese Empire capitulated. The Japanese garrison numbered 2,200 troops. Some 1,600 Japanese died on Wake Island during the war. Some 600 died in the air raids, while most starved to death. Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara and Lieutenant Commander Shoichi Tachibana of the Imperial Navy were sentenced to death for war crimes committed under their orders at Wake. Sakaibara was hanged on Guam in 1947. Tachibana’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

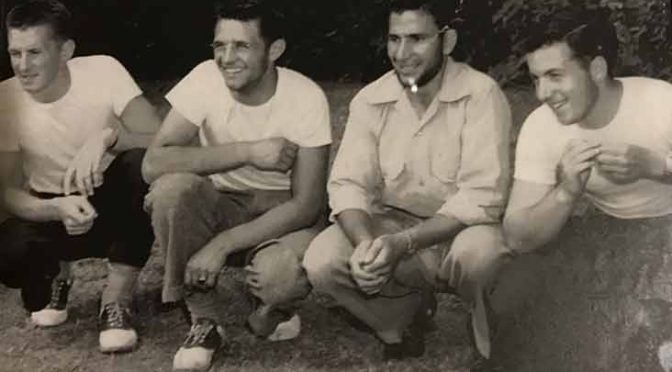

In 1981, Wake’s civilian defenders received US Army veteran status, being considered eligible for veteran’s benefits just like their compatriots in the armed forces. In 1988, a memorial, the “Harry Morrison and Civilian Construction Memorial,” was erected and dedicated in their memory. As Pagoaga’s son Richard recalls, “All his fellow POWs formed a life-long bond and held annual reunions until their very end” [5]. Goicoechea and Pagoaga, together with their inseparable friends Murray Kidd and George Rosandick, joined the Wake Island Survivors in a ceremony that took place during the unveiling of the monument in 1988. Pagoaga’s brother, Albert Pagoaga, a WWII veteran of the Marine Corps, accompanied them on the trip.

Despite the suffering they endured for almost four interminable and cruel years, the surviving Basques of Wake lived long and full lives. They found their why in life and forged a how to survive. George Acordagoitia, who died the youngest, did so at the age of 65. Joseph Mendiola died at the age of 76, Ignacio Arambarri at the age of 84, Angel Madarieta at the age of 88, and the two inseparable friends, Richard Pagoaga and Joseph Goicoechea, died, one after the other in 2015 and 2016, at the ages of 93 and 95, respectively. Goicoechea was the last Basque survivor of the Battle of Wake, and one of the last in the country. They were the first anonymous heroes in an atrocious, unprecedented war that devastated the known world, establishing a new international order that lasts, in a way, to this day.

References

[1] In Roberts, Bill. (January 10, 2017). “‘No one could believe he was alive.’ Boisean survived WWII capture on Wake Island”. Idaho Statesman (Boise, Idaho).

[2] The Times-News (Twin Falls, Idaho, May 27, 1945. Page 6).

[3] In Roberts, Bill. (January 10, 2017). “‘No one could believe he was alive.’ Boisean survived WWII capture on Wake Island”. Idaho Statesman (Boise, Idaho).

[4] In Roberts, Bill. (January 10, 2017). “‘No one could believe he was alive.’ Boisean survived WWII capture on Wake Island”. Idaho Statesman (Boise, Idaho).

[5] Cited in the obituary of Richard Pagoaga, written by his son Richard Jr. Pagoaga.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.