Four Basque brothers, four very different ways they experienced the immigrant life.

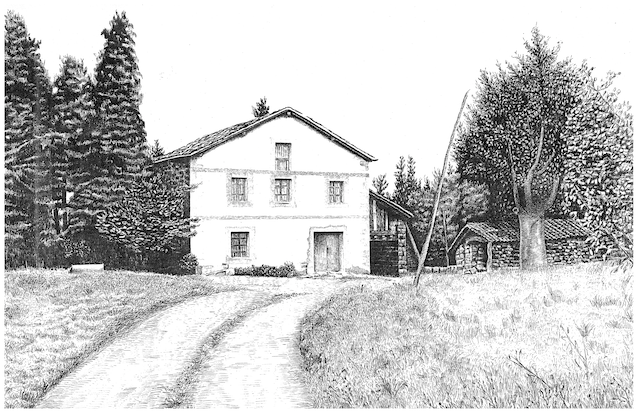

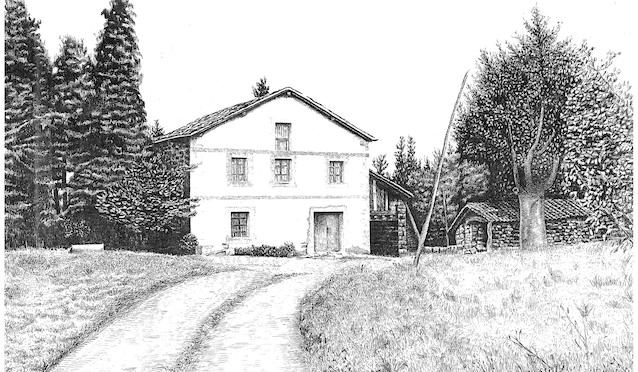

Goikoetxebarri is a typical baserri nestled into the woods just outside of Gerrikaitz, one of the two barrios that together make up the village of Munitibar. Munitibar is small, maybe 500 people, and lies in the heart of Bizkaia, in the center of a triangle formed by Durango, Gernika, and Lekeitio. Goikoetxebarri was the home of the Uberuaga clan: the patriarch Pedro Uberuaga Kareaga and the matriarch Justa Urionaguena Magunagoikoetxea and their children, eventually seven in all. While the baserri provided the essentials, for such a large family it wasn’t enough. And there weren’t many opportunities in Munitibar — there wasn’t much industry to speak of. While it wasn’t so long ago that there used to be a few ironworks, mills, and even a gypsum mine, today there is just a factory of construction materials and an agricultural coop. Beyond that, there are just a few bars, a couple of churches, the fronton, and the school. To make a living, one had to look beyond the borders of this small village.

Several of the Uberuaga children left home at a young age – as young as ten years old – to work. There simply wasn’t enough money at home to support them all, so they had to work to help the family. Often, necessity drives the search for opportunity, and, as these kids grew up, they took advantage of what opportunities they could, each finding their own way. What I find fascinating about this family is how each of the brothers followed very different paths, together spanning the spectrum of the Basque immigrant experience.

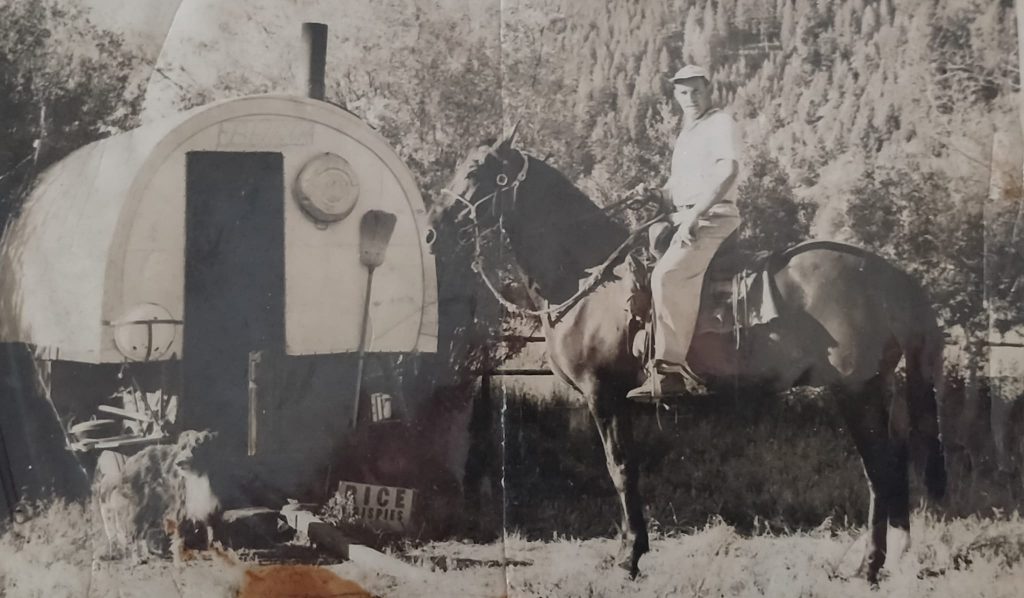

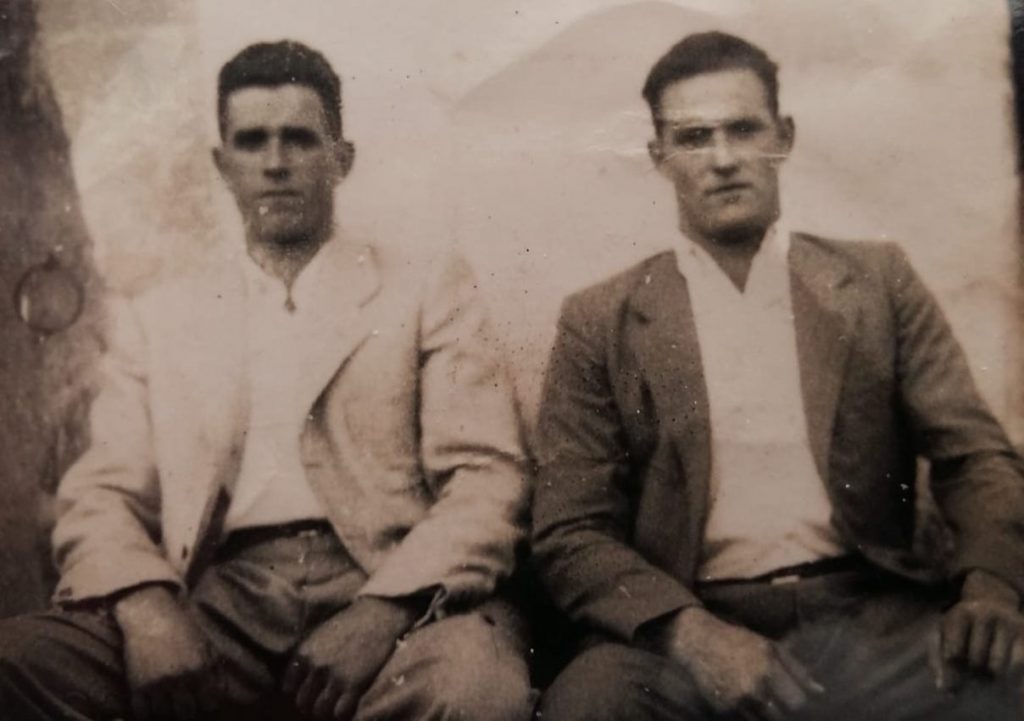

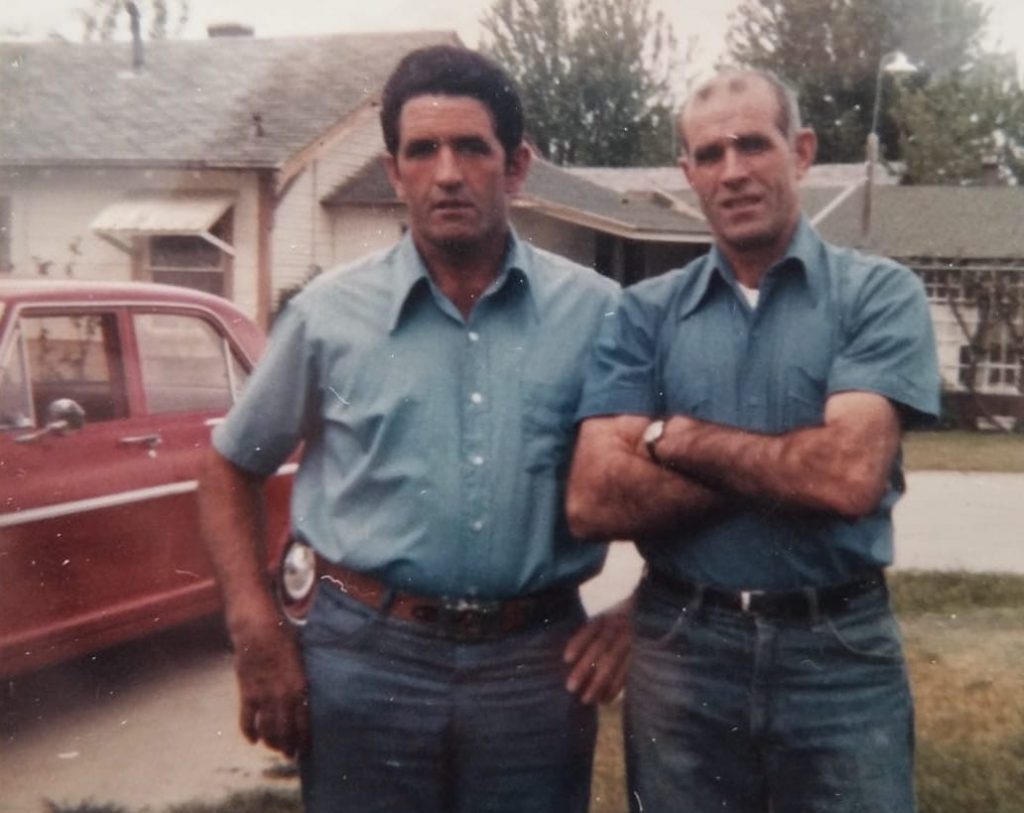

The three youngest brothers each made their way to the United States, attracted by the opportunities that sheepherding promised young Basques. Juan Jose – Tio Joe – was the first. (For many years, Tio Joe was Uncle Tio to me… my dad called him “tio” so I just assumed that was his name…) Born in 1924, he arrived in the US in 1952. After his stint as a sheepherder and a lumberjack, Joe worked in a plywood mill for Boise Cascade. Joe never married. He had a shiny, bright red car, with white pin stripes, that embodied cool to me. Eventually, in 1984, he retired after 32 years in the US and returned back to the Basque Country at the age of 60.

When he moved back, he joked with his brother Juan and nephew Jon that he was sick and that he wouldn’t last much longer. But, Joe is still going strong, the last of Pedro and Justa’s children still alive. While his body is certainly weaker than it was when I knew him as a kid – when he would show off his huge biceps, saying he had swallowed big eggs that formed his massive arm – his mind is still sharp. When he was just a little younger, he drove almost every evening from his home in Durango, which he shared with his brother Juan, or Amorebieta, where he now lives with his niece Rosario, to Munitibar, where he could always be found having dinner with his friends, usually in the Ondamendi Taberna. After dinner, he often made his way to his nephew Martín’s bar, the Herriko Taberna, to play cards.

Tio Joe has come back to the United States often, usually for Jaialdi, though, as he gets ever closer to 100, his traveling days are likely over. Just before his last trip, in 2014, we were visiting him and the rest of the family. His niece, Rosario, was away on vacation. Joe and his other niece, Begoña, and her husband, Javier, were planning to board a plane just weeks later to visit my parents and friends. The stubborn old Basque that he is, Joe decided it was the right time to trim some hedges, so at the age of 90, he climbed up a precarious ladder to cut away the branches. He fell, and had to be taken to the hospital. While he ended up ok, and was able to get on the plane, the whole time he was waiting for the ambulance, all he could do was worry about the “broncas” – the scolding – he was going to get from Rosario…

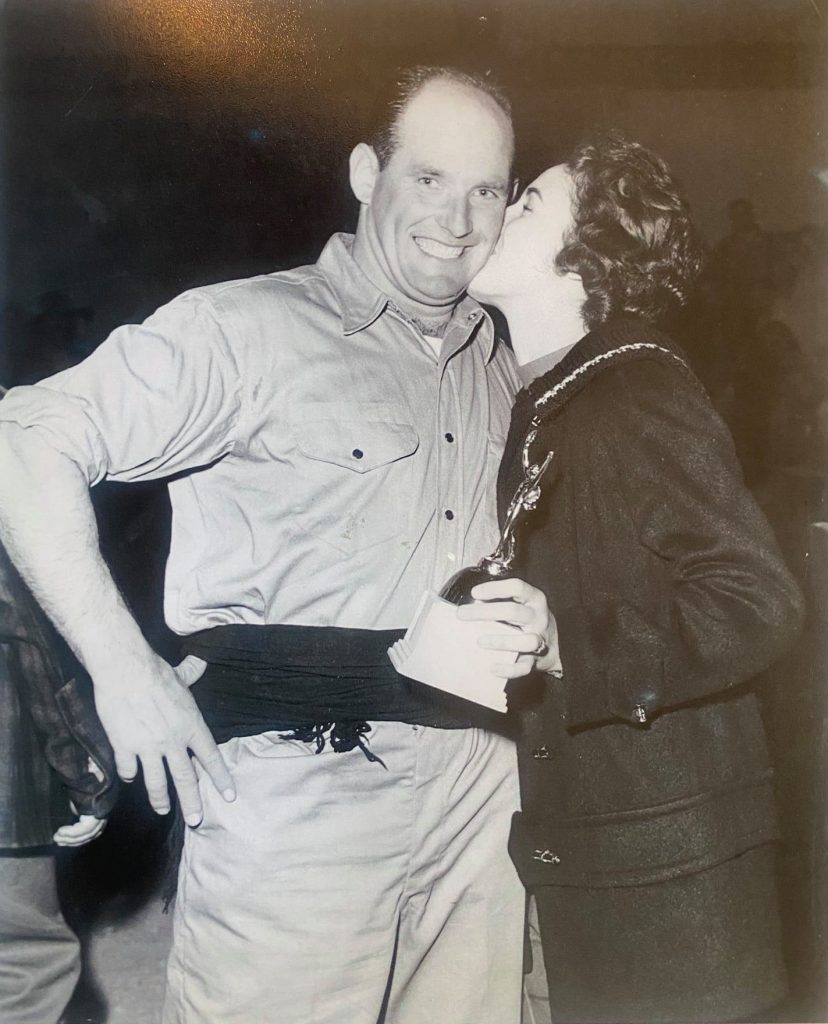

Joe’s younger brothers soon followed him to the United States, presumably drawn by Joe’s stories of the wonderful opportunities the American West offered. Juan came in 1956, when he 29 years old. Back in the old country, Juan had already gained fame, nicknamed the Leon de Oiz – the Lion of Oiz – a champion txinga carrier. On the day before he left for the US, he beat a rival – Gandiaga – by carrying two weights, each weighing about 100 pounds, over 850 feet. Juan came on one contract, returned back to his native Bizkaia, and then came on a second contract to herd sheep. His immigration status was different than Joe’s – Juan wasn’t allowed to hold any job other than sheepherder while Joe spent half of each year cutting wood. After a second contract, he returned to the Basque Country for good. But, during those six years, Juan earned enough money that he could have bought five apartments and a car. Now back in the Basque Country, Juan settled down. He married Felisa Urionabarrentexea and had a son, Jon. Sadly, his first wife died in 1975 when Jon was nine years old.

When I first met Juan, during my first visit to the Basque Country in 1991, Juan was confined to a wheelchair, the result of severe thrombosis. However, his strength was still legendary. During one of my visits, I joined him, Joe and Jon at a sporting event that was held in honor of his career carrying weights. Juan died in 2001.

The youngest son, Santiago – Tio Santi – came a year after Juan, when he was 28 years old. As his older brothers, he came on a sheepherding contract. When my dad, Pedro, came in 1961, Santi was still herding sheep, and became my dad’s boss. While Santi was out watching the sheep, my dad took care of the camp. In 1972, Santi started working at a Boise Cascade plywood mill in Emmett, Idaho – he worked there until he retired in 1991. Shortly after he began working at the mill, he married Frances Chacartegui Toolson and they made their home in Boise. Santi was a staple at the Boise Basque Center, and was always ready for a game of mus. Santi wouldn’t make it back to the Basque Country more than a few times after that. When Juan’s first wife died in 1975, Santi and Francis made a trip to the old country. But, that was Santi’s last time in his native country. When Juan himself died in 2001, they wanted to visit again, but the attacks on 9/11 disrupted those plans. Santi died not too long after, in 2002.

While Santi was by far the closest to us, physically, I never really got to know him. We never really saw him that much when I was a kid. When he lived in the United States, we saw Joe a lot more, and I’ve of course seen Joe many times since, as we each skip across the ocean. I even got to know Juan, who I only met a few times, better. It is funny how life happens.

The eldest brother and my aitxitxa, Teodoro, born in 1915, stayed in the Basque Country. He never step foot in the United States. As the oldest child, Goikoetxebarri was his responsibility, though the younger siblings often sent money to help with the upkeep of the baserri. Teodoro married Feliciana Zabala Idoeta, and they made their home in Goikoetxebarri. They had eight children – six boys and two girls. Just as with the previous generation, several of the children started work at a young age to help the family. Over the years, Teodoro worked various jobs, including at a paper mill in Durango and making charcoal. He would often work two shifts, taking on that of another worker, to earn that much more. Teodoro died young, only 56 years old, of lung cancer in 1971, the year I was born. Of those eight kids, only my dad – the eldest – followed his uncles to the United States.

Each of these four brothers lived the Basque immigrant story in very different ways. Teodoro, the oldest, became the new patriarch of the family baserri and never left the Basque Country. Juan did two contracts as a sheepherder and returned home. Though the work was hard, he appreciated the economic opportunities it had given him. José – Joe – also came as a sheepherder but ended up spending the rest of his working life in the United States. However, the lure of his native land never left him and he returned once he retired, enjoying another 38 years and counting in his native land. And Santi made the US his permanent home. Each followed a completely different path afforded by the opportunities of the time.

There were three other kids in that Uberuaga clan of Goikoetxebarri. The only girl, María, left home early when she was only ten years old, to live with an aunt and help support the family. Eventually, she made her home just up the mountain from Goikoetxebarri at another baserri, Kortaguren. Emilio, the second oldest brother born in 1917, was killed in 1938 in the Spanish Civil War. The last brother, Eusebio, also died young at the age of 31.

Many thanks to my cousin, Jon Uberuaga, for filling in so many details and sending these great photos, and my wife, Lisa Van De Graaff, for the critical eye.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Gracias Blas,por conpartir,Conozco biem a tu familia me gostado mucho,Eskarrikasco ,aurora

Gracias a ti, Aurora! Siempre estoy buscando mas historias de ellos, si tienes alguna… 😉