This article originally appeared in Basque and Spanish at Euskalkultura.eus on January 13, 2022.

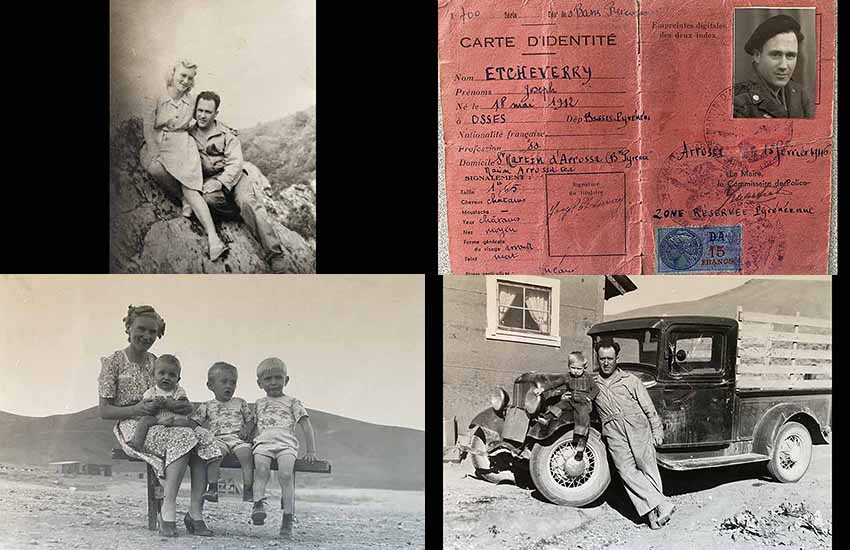

On this Memorial Day, we bring you the story of Joseph Etcheverry and Helena (Santana) Etcheverry, a story of our diaspora that, like many others, unites and connects origins in Euskal Herria — in this case Ortzaize and Arrosa, in Nafarroa Beherea — with trajectories that take us through the Basque communities in the world, in this case Ayacucho, in Argentina, and Battle Mountain, in Nevada, where the couple formed a home and raised their family. Joseph Etcheverry, who participated in the European stage of WWII, died in 1988, and Helene followed him on October 2, 2021, just after turned 100 years old.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

Throughout 1929, a new generation of young Basques arrived in the United States of America. On April 3, at the age of 17, Joseph Etcheverry Oxoteguy, a native of the Nafarroa Beherea town of Ortzaitze, made that journey. Along with him, a group of compatriots in their twenties arrived at the port of New York aboard the ocean liner Paris; among them Jean Bastanchury, Jean Elgart, and Jean Ernaga, all three from Urepele, Jean Bidegaray, from Mendibe, Pierre Duhalde, from Biarritz, and Germain Elissondo, from Bithiriña. They all joined the sheep industry in the American West as sheep herders, pursuing the dream of a better life that many of their ancestors had conquered.

Little could these young immigrants imagine that a few months after their arrival, on October 29, the New York Stock Exchange would collapse, initiating one of the largest economic recessions in US history. The so-called Great Depression began and lasted until 1933. If at the beginning of 1929 unemployment stood at 4%, in 1930 it became 9%. In 1933, it reached 25%. The 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, made into a film by John Ford in 1940, perfectly reflects the horrors of the consequences of the recession and the deep despair of those who, at one point, saw their own Promised Land in America.

Joseph Enlists in Nevada

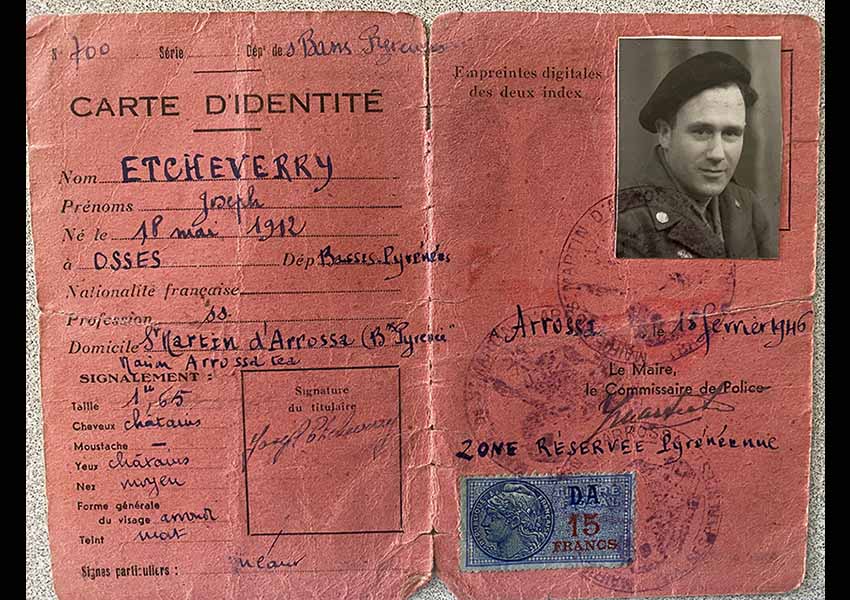

Joseph was headed to Battle Mountain, a town in central Nevada, on the way between Reno and Salt Lake City, Utah. His cousin Pierre “Peter” Oxoteguy, who had entered the country three years earlier when he had just turned 17, lived in this small, predominantly mining town in Lander County. From his arrival until his enlistment into the United States Army in October 1942, Joseph worked as a shepherd. At the time of his enlistment, he was working for the Eureka Land and Stock Co., living in the small rural town of Eureka – about 140 miles south of Battle Mountain – popularly known as the friendliest town on the loneliest highway in the country. He was 30 years old.

His family tells us that Joseph was aware of the invasion and brutal occupation of his native country by Nazi Germany in 1940. Two years later he had the opportunity to enlist and he did not hesitate to take advantage of it, although he was not even a US citizen, like tens of thousands of other immigrants who fought in World War II under the banner of the stars and stripes. In fact, despite his sacrifice and loyalty to his host country, Joseph would not achieve American citizenship until June 19, 1950.

In the European Theater of Operations

Joseph was assigned to the 485th Air Service Squadron, 9th Service Group, which would be mobilized and deployed to the European Theater of Operations. The 9th Service Group was based at Andover Aerodrome, in Hampshire, England. It was part of the 70th and 71st Fighter Wings (composed of P-47 Thunderbolt and P-38 Lightning fighter-bombers) of the Ninth Air Force, which was the tactical combat component of the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe and fought enemy forces in Normandy (D-Day), France, the Netherlands, and in Nazi Germany.

According to his daughter, Bernadette Etcheverry, Joseph participated in the Normandy invasion in June 1944. “I have a photo,” Bernadette relates, “of a big wedding that took place just after the Normandy invasion, in which the couple were so pleased with what had just happened that they asked the troop commander if a couple of men could take part in a photo with the wedding attendees. My father was one of the men.”

On January 10, 1946, Joseph was honorably discharged with the rank of Private First Class in Namur, Belgium. At the time he was assigned to the 473rd Air Service Group Headquarters and Base Service Squadron. Joseph was awarded the Bronze Service Star (attached to his Europe, Africa, and Middle East campaign ribbon) for his unit’s participation in the Northern France campaign (July 25, 1944 – September 14, 1944) which liberated most of France and Belgium.

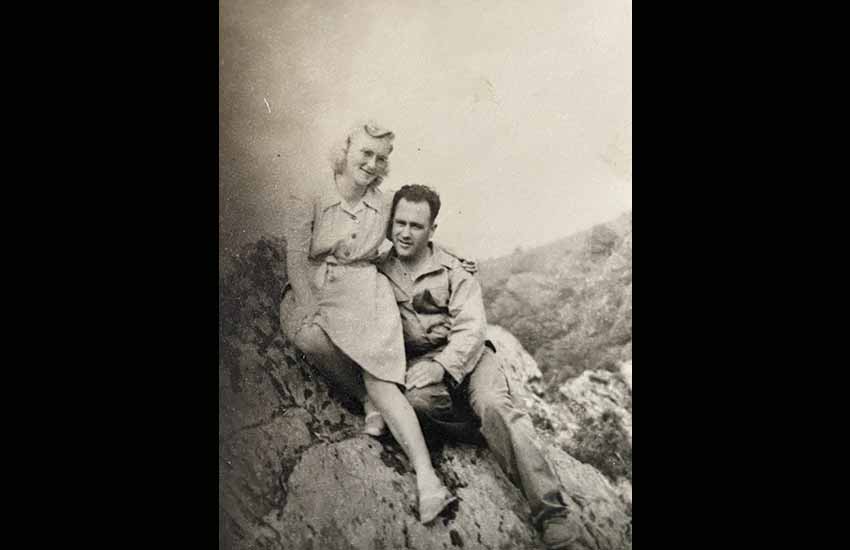

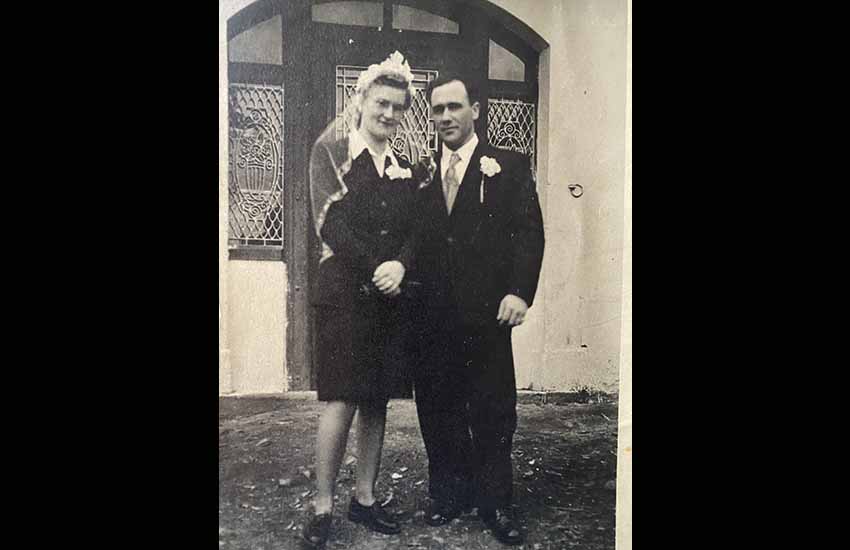

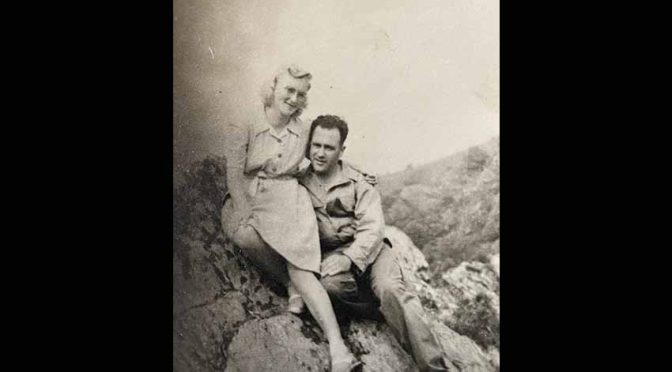

From Belgium, Joseph headed for Ortzaitze to visit his family. It had been 17 years since he had left. There he met Eléna or Helene Santana Anchartechahar, a young woman from the neighboring town of Arrosa, with whom he fell in love at first sight, marrying on February 27, 1946.

Helene was born on August 6, 1921 in Ayacucho, in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, where her parents had immigrated after marrying in 1911, hoping to start a new life. Three other daughters of the couple (Marie, Catherine, and Stephanie) were born in Argentina and a fifth (Marie Angel) would be born in Arrosa after the family returned to the Basque Country to take care of the maternal farmhouse, “Gerechitenia,” at the request of the family. While, in theory, Helene’s maternal uncle should have taken over the farm, he had died in the Great War. Helene was about two years old when she undertook what would be her first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.

Born in Ayacucho, Return to Arrosa

Helene and her sisters grew up in the Arrosa farmhouse. The family tells us how “life on the farm wasn’t always easy, but Helene loved working in the fields with her father and taking care of the animals.” “On Sundays she spent the afternoons with the nuns learning to do different sewing tasks.” The Great American Depression dragged down much of Europe’s financial and economic system. France also succumbed to the effects of the crisis, especially starting in 1931. Unemployment and poverty were a constant. Helene survived both the Great Depression and the subsequent Nazi occupation of Iparralde between 1940 and 1944, which “helped her deal with extreme hardship throughout her life.”

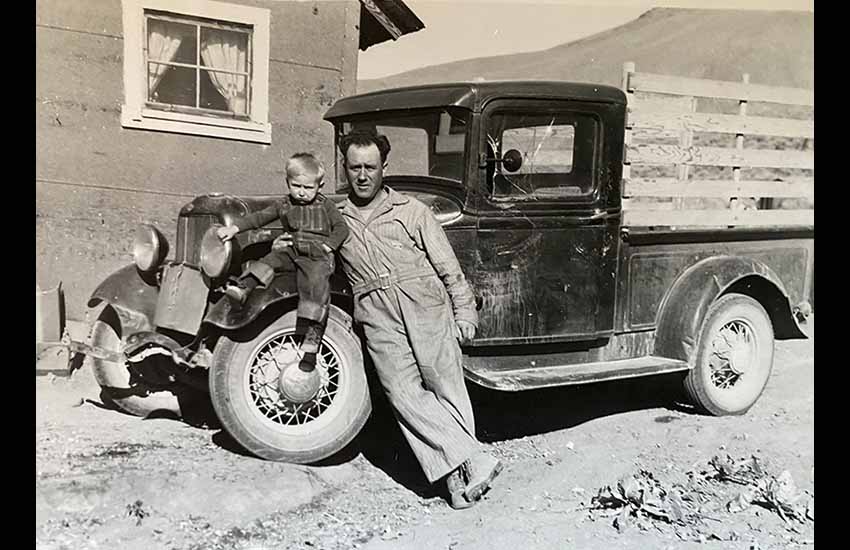

Joseph returned to Nevada shortly after their wedding, where he again worked as a sheep herder for the W.T. Jenkins Sheep Company. Joseph would never return to Euskal Herria. In 1947, Louise Jenkins Marvel, a great friend of the Basques, sponsored the visa of Helene and that of her son Alexander “Alex,” who was born on October 11, 1946 in Arrosa (Alex would die on November 6, 1965 near Reno, in a highway accident).

Helene and her baby flew from Orly Airport, Paris to La Guardia Airport, New York on Air France, arriving on July 13, 1947. Helene was 25 years old and Alex was 9 months old. They later boarded a train that took them to Reno, traversing most of the country. Her daughter Bernadette Etcheverry points out that “with her on her journey there were several Basques who helped her along the way, something for which she was always grateful.” Among them were two young men from her husband’s hometown, Joseph Oilamburu and Jean Lekumberry. The latter would later become the owner of the famous Gardnerville Basque bar and restaurant, Nevada JT Basque Bar and Dining Room. The emigration story of Helene’s parents was thus repeated a generation later with her and her son. They had crossed the Atlantic again in search of a new beginning. Joseph met his son for the first time, and he and Helene were back together.

Basque, the First Language of the Etcheverrys in Nevada

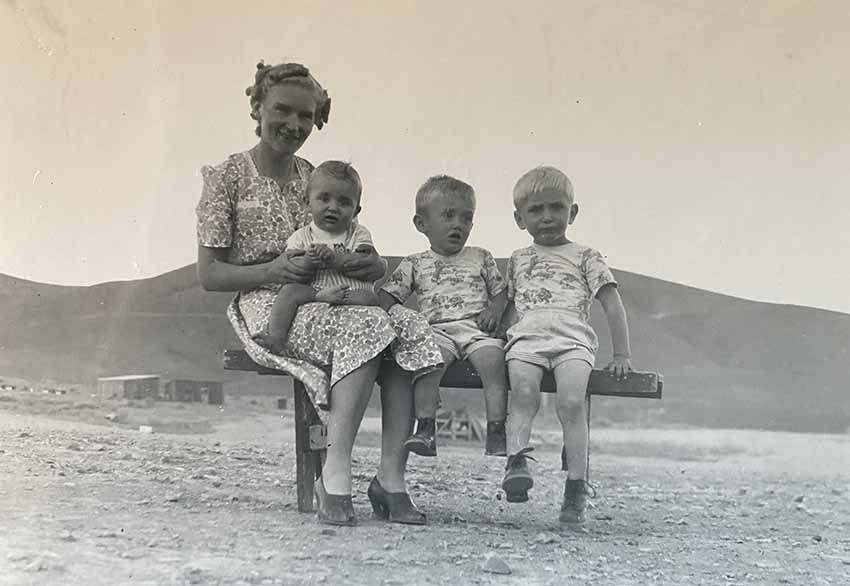

Louise Jenkins set them up at the Martin Ranch, a small cabin within the Jenkins’ main ranch. “The first few years were difficult for Helene,” says Bernadette. “But she went ahead with her plans to create a home for her growing family” in Nevada. Alex was joined by John, Raymond, and Bernadette. Her daughter remembers how Helene used to tell them that she “cried every day for the first two years of living in Nevada, but the dry, dusty heat finally made it hard to produce tears.” When Helene arrived in the country, she did not speak English and was self-taught, learning the language by reading books. At her house they only spoke Basque and this was the only language that her three oldest children learned at home. By interacting and playing with other children they began to learn some words in English. Only when they started school did they learn to communicate in English.

Sometime in 1948, Joseph began working in the mines in Natomas, a mining district about 20 miles south of Battle Mountain. The family moved into housing provided by the mining company. They remained there until 1956, the year in which they moved to Battle Mountain. Joseph got a job as a butcher at the town grocery store. He also built fences part-time for the Artistic Fence Company in Reno, Nevada, which later led him to building guardrails along the highway from the Wendover state line on the Nevada-Utah border. Utah, to the California state line, on the Nevada-California border. Joseph was getting older and finally took a job with the Lander County Water District, from which he retired when he couldn’t work anymore.

In 1985, after 37 years in the country, at the age of 63, Helene finally fulfilled her dream of becoming a US citizen. “She loved America and was always grateful for its help during the war, and for the kindness she received when she came as a stranger to a country she couldn’t even speak the language of,” confesses her daughter Bernadette Etcheverry. “Her greatest joy,” she continues, “was seeing the American flag fluttering in the breeze, and she couldn’t listen to the Star-Spangled Banner without tears coming to her eyes.” “She was Basque-American and she loved this country. And she still had a part of her heart that was 100% Basque.” Helene returned to her homeland for the first time to see her family in 1989, after 42 years, and she did so again in 1998, both times in the company of her daughter.

‘Oberenak,’ the Legacy in Nevada…

The story of Joseph and Helene follows paths similar to those pursued by many other families and generations of Basques. Euskal Herria is only understood in its entirety when the stories of those who for one reason or another had to leave its geographical confines are included. The country’s emigrant sons and daughters largely reflect the society they left behind. Joseph died in 1988 at the age of 75, at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Reno. Helene passed away only last year, on October 2, 2021, just two months after celebrating her 100th birthday.

Bernadette tells us that Helene celebrated her 100th birthday “with a parade full of balloons, flowers… and lots of well wishes from friends, family, and community members. Helene experienced the celebration and dance with joy in her heart. She sang along with music in Basque. At the end of the day,” her daughter emphasizes, “Helene mastered more than five languages, which is not bad for a girl born in Argentina in 1921, who she says she did not pass the fifth grade. Yes, she built a house in another place, but she worked hard to keep the memory of the house that her family came out of long ago. That day, her home came back to her.” Helene was one of the founding members of the Battle Mountain Basque association “Oberenak,” created in 1997. A lauburu and the words “Eskualdun-Fededun”, engraved on their tombstones summarize a Basque legacy in the United States that Helene and Joseph passed on to their four children, 14 grandchildren, 29 great-grandchildren, and 13 great-great-grandchildren.

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”

Greetings,

what a lovely story!! Saint Martin d’ Arrossa and Osses–beautiful country. I wish my Dad was alive to show him the photo of Joseph Etcheverry.

Dad mentioned an American by the name of Etcheverry that he met when he was involved in the French Resistance who was from around Arrossa. Dad would not speak much of the war except with my uncle Luis –he would say –“just in case “they” return and we have to do the same thing again”. Also “look out to the East.” Bitter sweet memories.

Thank you for posting this story.

Monique

It always surprises me how small the Basque world is. I wouldn’t at all be surprised if it was the same Etcheverry! 🙂

My grandmother was also a Etcheverry from Garazi!the world war two did not begin until 1939 to 1945 so where was this war in 1936?

It’s a small world! The Spanish Civil War started in 1936, ended in 1939, so immediately proceeded World War II.