Humans have always needed explanations for why bad things happen. If a crop went bad or a violent storm destroyed the harvest, maybe a wizard was the cause. Or maybe someone had not paid the proper tribute to a god or goddess. Bad dreams and nightmares are probably one of the most confounding experiences for people. Why would our brains subject us to such misery? Well, according to the Basques, it might be because Inguma was sitting on your chest and squeezing your throat.

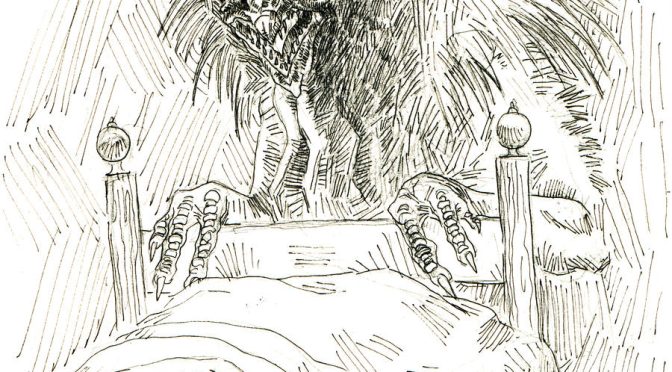

- Inguma (called Maumau in some parts of Euskal Herria) is a malevolent spirit that comes into peoples’ homes once they are asleep. He often enters in the form of a fog that squeezes through cracked windows or door locks. He presses on the sleeper’s throat, making it hard to breathe and instilling fear in his victims. He is the bringer of bad dreams and nightmares. At his worst, Inguma can cause sleep paralysis and even death. It’s as if he drowns his victims.

- In some places, he is envisioned as a heavy animal, maybe a black dog, that sits on the sleeper’s chest. Interestingly, Inguma can also mean butterfly in Euskara. I’m not sure if that is coincidence or not.

- Throughout the Basque Country, there are incantations people invoke to keep Inguma at bay. A few of these include:

- In Ezpeleta: Inguma, enauk hire bildur, Jinkoa eta Andre Maria Artzentiat lagun; Zeruan izar, lurrean belar, Kostan hare Hek guziak kondatu arte Ehadiela nereganat ager.

Inguma, I do not fear you. I take God and Mother Mary as protectors. In the sky, the stars; on earth, the blades of grass; on the coast, the grains of sand; until you have counted them all, do not come to me. - In Ithorrotz, they add: Hi, aldiz, jin akitala, Gauarguia!

Instead, you come to me, Gauarguia! (Gauargia, the night light, is a benign spirit that appears as a point of light and is a counter to Inguma.) - In Amézqueta: Amandre Santa Inés, / bart egin det amets; / berriz egin eztezadala / ez gaitzez ta ez onez.

Lady Holy Mother Agnes, I dreamed last night; may I not dream again, neither for bad nor for good. (Saint Agnes, the Virgin Mary, and Saint Andrew are often invoked to protect against nightmares)

- In Ezpeleta: Inguma, enauk hire bildur, Jinkoa eta Andre Maria Artzentiat lagun; Zeruan izar, lurrean belar, Kostan hare Hek guziak kondatu arte Ehadiela nereganat ager.

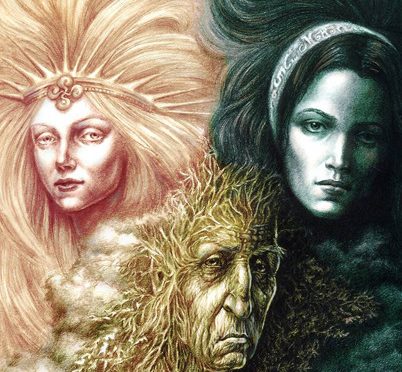

- Other spirits similar to Inguma are Aideko, who is responsible for all diseases whose natural causes are not known, and Gaizkiñe who, by forming rooster-headed figures with the feathers of the pillow, causes serious illness to those who lie on it. Only by burning such figures can the disease be cured.

Primary sources: Barandiaran Ayerbe, José Miguel de; Elia Itzultzaile automatikoa. INGUMA. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2024. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/inguma/ar-74437/; Inguma, Wikipedia