Over 100 years ago, in 1921, José Miguel de Barandiaran began publishing a series of articles under the banner of Eusko-Folklore. His work was interrupted by the Spanish Civil War but in 1954 he resumed publishing what he then called his third series of articles. These appeared in the journal Munibre, Natural Sciences Supplement of the Bulletin of the Royal Basque Society of Friends of the Country. While various writings of Barandiaran have been translated to English, I don’t believe these articles have. As I find this topic so fascinating, I have decided to translate them to English (with the help of Google Translate). The original version of this article can be found here.

Preliminary Notes

Nearly forty years have passed since we began the research work that was to precede the first publications of EUSKO-FOLKLORE. Then, as today, we outlined our plan in these sentences: “Physicists study the characteristics of bodies and all the observable virtues and effects produced in them, thereby having managed, in a certain sense, to master many of the forces of Nature. Why shouldn’t the same be done with social bodies, that is, with those human groups called peoples and with the phenomena that occur within them?”

“Among the characteristics of such bodies or social groups, there are those that come through biological inheritance and are studied by Physical Anthropology, and there are those that come solely through social inheritance. The latter form the field of study of Cultural Anthropology or Ethnology, which today extends its research to all countries of the world.”

To collaborate in this great endeavor, in 1921 I founded the Ethnology Laboratory (later known as IKVSKA), which then undertook research into the social traditions of the Basque people. I encountered resistance and misunderstanding; but there was no shortage of assistance, such as that of my teacher Aranzadi, who had introduced me to this work, and that of the illustrious ethnologist P. W. Schmidt, then editor of the important international journal Anthropos, who encouraged me to continue my work, first by letter and shortly afterward by speaking to me in Tilburg (Holland), where I met him at a conference on religious ethnology.

The Ethnology Laboratory has been publishing the results of its work for 14 consecutive years, publishing an annual volume or Yearbook of Eusko-Folklore and monthly sheets also titled Eusko-Folklore, in which I collected ethnographic materials of various kinds, especially mythological ones.

We are now attempting to resume publication of these sheets, beginning their third series with new materials, the result of research conducted or that we are organizing in the Ethnology Laboratory of the C. N. Aranzadi Group.

Our method will be the one currently used in Ethnography. We will endeavor to locate, date, and weigh each event, highlight its variations, to later establish its area of dissemination and determine the phases of its evolution. In this way, we will be able to understand the core of the social traditions that shape our people, its past history, its current orientation, and its possibilities.

As an introduction to this new series of materials, we will now outline the topics covered in the previous ones published in Vitoria, Bayonne, and Sara. Some of these topics appear only in one region, others extend to the entire country, and others go beyond, perhaps covering vast areas on all continents.

Themes of Eusko-Folklore, the First Series

Shape of the world: substantially flat, not round, immensely large, without known limits (according to the beliefs of Ataun, Olaeta, Cortézubi, Iciar, and Leiza).

Interior of the earth: a delightful place where there are rivers of milk and honey, abode of spirits and the souls of ancestors (Ataun). There is also the place of torment for the wicked.

Fabulous treasures are preserved in the bowels of the earth (Cortézubi, Arrancudiaga, Aulestia, Placencia, Abadiano, Ataun, Elorrio, Gaztelu, Oyarzun, and Leiza).

Various spirits live within the earth, such as Mari and Sugar, who take the forms of a bull, a horse, a ram, a goat, and a snake, as well as the Basajaun, Tartalo, the lamias, the witches, the gentiles, the Moors, etc.

A luminous cloud (or a star) announces the coming of Christ and the end of the Gentiles (Urdiain, Ataun, Segura, Orozco, Zaldivia, Oyarzun, Arano).

Chasms that connect with ancient houses or homes: that of Agamunda with Andralizeta in Ataun, that of Malkorbe with Sales in Elduayen. etc.

Young woman taken to the interior of the earth by a supernatural being in the form of an animal

(Berástegui). A young woman falls into a chasm and there appears a piece of clothing

or a finger of her hand in a distant spring.

The supernatural being Mari issues oracles at the bottom of her chasm, feeds on “no,” demands that visitors enter and leave her dwelling facing her; she kidnaps a young woman, seizes a ram.

A mother’s curse causes her daughter to transform into a supernatural being of the underworld or into Mari.

A lamiñaku deprived of help because her persecutors assume a misleading name (Elanchove, Ataun, Cortézubi, Tolosa, Izarraitz). A theme from the Polyphemus cycle (K 602 Stith Thompson: Motif-Index of Folk-Literature: FF Communications, Helsinki, 1932-1935), which also has its paradigms in Germany and Denmark.

The theft of the comb and the claim of the lamia, the gentile, the Moor.

The dragon that devours a person every day and the young woman freed by a hero (Ataun). These themes have spread to almost every country in Europe, Persia, Japan, Central Africa, Canada, etc. (B 11. 10, S 262, and R 11. 1. 3. Stith-Thompson: Motif-Index…).

Robbing and cursing the Gentiles (Ataun, Leiza).

Herculean forces of the Gentiles, the Baxajaun, the Mairu, Errolan, and Tártalo.

Tártalo, a cannibal character or the Polyphemus of Basque mythology. Caves inhabited by Mari, the Mairu, the Sorgin, the Lamina, the Intxixu, the Ieltxu, or the Iditxu.

The mutilated Sugoi or snake of Balzola (Dima) tries to take revenge on its aggressor by luring him with gifts (Yurre).

Vestiges of religion and worship in caves and chasms.

Mountain spirits and the theft of the first seed of wheat from the Baxajaun of Muskia (Ataun). The Baxajaun deceived by a man and imprisoned.

Apparitions of the souls of the deceased in the form of light, the shadow of an animal.

The boundary stone transplanter returns to the world with his burden on his shoulder (Ataun, Aranaz). A theme repeated in many regions of Europe.

The wandering hunter and his dogs (Ataun, Oyarzun, Placencia, Cortézubi).

Supernatural witches. The danger of denying their existence and answering three times to their neigh (Ataun, Elduayen, Guerricaiz, Elorrio, Lequeitio).

Everything that has a name exists (Izena doon guztie emen da) (Ataun, Oyarzun, Placencia, Cortézubi).

Toponymy and the name sorgin (witch).

The sorgin in the form of vultures (Orozco).

The sorgin who steals apples is surprised in her underground dwelling, and in a fight with the hero, her tongue, which has magical power, is torn out (Ataun).

Human witches. How to treat them: don’t wound them an even number of times, don’t invoke them three times, don’t strike their body, but rather their shadow. (Ataun, Elduayen, Andoain, Arbeiza, Narcue, Guerricaiz, Zarauz, Oyarzun, Cegama).

Days and places where witches gather. Night patrols.

The sign of the cross drives away witches. They are powerless against rue and celery.

A muleteer secretly attends a witches’ meeting where he learns of the remedy that would cure the king’s daughter: she is cured by applying it, and the muleteer is rewarded. Another muleteer later attends a witches’ round and is discovered by them and cruelly punished. (Ataun, Orozco, Salvatierra, Echagüen, Arbizu).

Witches’ journey by sea: “with each stroke a hundred leagues” and the old man hiding in the same boat (Bermeo).

Witch who, enveloped in a wave, threatens to sink a boat carrying fishermen and is injured by them. (Azcoitia).

Sasi guztien gañeti eta odei guztien azpiti (above all the brambles and below all the skies): a phrase witches use when setting out on their journey to their meeting places. Punishment for anyone who mis-speaks the phrase.

Witches’ metamorphoses: they take the forms of oxen, donkeys, pigs, dogs. One becomes a witch by walking three times around a church, a cemetery, or certain trees.

Prakagorri or spirit familiars of witches, in the form of insects, which grant strength to their possessors.

Anthromorphic rocks and explanatory legends.

Legendary boulders: (Sepulturarri, Ipistekoarri, Aranekoarri, Laminarrieta, Jentillarri).

Boulders hurled by Sugaar, by Mikelats, by Baxajaun, by Gentiles, by Roland, by Samson: Theme from a very extensive cycle. Known in ancient Greece and in Nordic countries, such as Estonia, Finland, Lapland, and Norway, according to Stith Thompson, it reaches a considerable concentration in the Basque Country (Ataun, Atxispe in Larrabezúa, Arrancudiaga, Orozco, Cenarruza, Motrico, Placencia, Vergara, Cerain, Urdiain, Aralar, Ursuaran, Segura, Cegama, Tolosa, Urnieta, Oyarzun, Ibiricu, Hendaye, Ezpeleta, St. Just-Ibarre, Errazu, Leiza, Urroz, etc.).

The Church of La Antigua de Zumárraga was built with stones thrown by Gentiles from Aizkorri, as in Denmark, Sweden, etc., according to the Motif Index.

Stones with tempting inscriptions and the disappointment of those who hoped to find treasures beneath them. (Cesama, Vergara, Cortézubi, Sara). A theme that extends throughout northern Spain, with the event located in “La Collada” (Gete, in León) and in the prehistoric rock or monument “Peña Tu” in the Sierra Plana de Vidiago.

Use of stone in magic: to cure illnesses, to ward off witches, and to protect against lightning.

Rocks associated with saints, such as those of Arrechinaga (Marquina), Ambabijiña-arri (in Aralar), and Amabirjiñen-sillea (in Aizkorri).

Land subsidence and rockfall to punish violators of Sunday rest (Cenarruza, Ajanguiz, Oyarzun).

Footprints, handprints, slingshots, etc., that the Gentiles, the saints, Roland, the devil, left marked on certain rocks in Torrano, Antzuitza (in Motrico), Elosua, Ata (in Madoz), Markitola (in Ezcurra), Ereñusarre (in Ereñu), Atxarre, Gaztelugatx, Santa Lucía de Llodio, Zalba, Goikogana (in Oyardo), Kurlutxu (in Lequeitio), Olarte (Orozco), Atxolin (Placencia), Zapata (in Oñate), Amabirjiñen-iturri (in Aizkorri), Santuane (in Amézqueta), Isone (in Amézqueta), Amabirjiña-arri (in Aralar). This theme, which reaches such a dense concentration in the Basque Country, has appeared on all continents since ancient times (A 901, Stith Thompson: Motif-Index).

Animal footprints, such as those of horses, of sacred donkeys that caused miraculous springs to gush forth (Armiñón, Bujanda, Ancin, Gauna, Goizueta, Zarauz, Peñacerrada).

Stone in various popular uses and industries.

Stone as an amulet (rock crystal, stone axe, flint blades).

Prehistoric monuments used as boundary markers, as objects of legends and popular customs: making the sign of the cross and praying when passing by a dolmen.

Tooth amulets: those of a hedgehog and those of a horse.

Fallen teeth are offered to the bat, to Mari of the roof, to Mari of the kitchen stove, to Mari of the henhouse.

Prayers addressed to the cow of San Antón and the Moon.

Offerings to the dead: lights and food.

Churches and hermitages in popular belief: neighborhood struggles regarding their location in Carranza, Rigoitia, San Miguel de Ereñusarre, Santa Eufemia de Aulestia, Andra Mari de Ceánuri,

Mendata, Muxica, Antigua de Ondarroa, Santa Cruz de Berriatúa, de la Encina de Arceniega, Aránzazu, Iciar, Antigua de Zumárraga, Ezozia de Placencia, San Martin de Ataun, Amézqueta, San Lorenzo de Berástegui, Amasa, Aya, San Vitor de Gauna, Mañaria, etc.

Miraculous apparitions of images: Saint Catherine of Badaya, Our Lady of the Encina, Our Lady of Aránzazu, Our Lady of Oro, the Cross of Aizkorri, Our Lady of Muskilda, the Virgin of Puy, Our Lady of Ujué, etc.

Houses collapsed and lakes formed at their sites as punishment for misconduct (lack of compassion for the poor) in Caicedo and Arbeiza.

Continuity of worship in the same places: Christianized pagan temples, according to indications, in San Esteban de Morga, in the church of Forua, in Armentia, in Donela (depopulated in Iruña), San Martin de Asteguieta (destroyed in 1930), San Ginés de Pangua, in Araya, in Ibarguren, in San Miguel de Ocariz, in San Román in Urbina de Basabe, in Andra Mari de Albéniz, in Our Lady of Arzanegi (Ilarduya), in Margarita, in San Pelayo de Ircio, in Cambriana, in Our Lady of Elizmendi (Contrasta), in San Miguel de Atxa (Gobeo), in Our Lady of Uralde (in Grandibar), in Foronda, in Luzcando, in San Bartolomé de Angostina, in Santa María de Assa, in San Sebastián de Gastiain, in San Miguel de Arroniz, in Urbina de Basabe, in Santa Magdalena de Aranhe (near Tardet), in the Marañón cemetery, etc.

Fountains related to temples and other manifestations of worship and superstitious beliefs in Araya, in Narbaja, in Arbulo, in Cabriana.

Lamiña as a spirit of springs and caves. Falling in love with a young man from the village, he recognizes that she is not a human person when he sees her feet, which are like those of a duck. The marriage does not take place; but the young man later dies, and the lamiña rides in the funeral procession to the church door.

The lamiña who pesters a woman with frequent requests for food is punished by her husband, who sticks a spit in her one eye on her forehead.

A lamiña seizes a man to eat him… However, she promises not to take his life while the man recounts the woes of the flax. Meanwhile, the rooster crows and the lamiña flees, leaving the man unharmed.

The pregnancy of the lamiña and the rewarded midwife (Guizaburuaga, Santimamiñe,

Ogoño, Esquiule). A theme repeated in the Isturitz cave and in the Akelarre cave in Zugarramurdi.

The lamiña disappear as a result of the annual litanies or rogations received in the hermitages (Orozco, Cortézubi). They disappear when the hermitages are built (Dima, Sara).

The hermitages and medicinal or miraculous springs: Our Lady of Remedies in Ataun, Andra Mari and Ur-bedeinkatu in Ciordia, San Juan Iturri in Yanci, San Juan de Murgoitio in Berriz, Kristoren Itturri in Elduayen, Santa Polonia in Urquiola, Sandalli or Santeli in Oñate.

Cave hermitages: of the Trinity in Santa Eulalia, Amabirjiñen-solue (now closed) or the place where the image of Our Lady of Bidarte was found in Ondárroa, of the Virgin of Puy in Estella, of the Virgin in Salinas de Oro, of the Virgin in Oskia near Irurzun, Our Lady of Ujué, San Miguel de Excelsis in Aralar, Arpeko-Saindua in Bidarray.

Churches built by Gentiles: Oyarzun, Antigua de Zumárraga, Elgueta, Xemein, the hermitages of San Miguel and Aitziber Andria (Our Lady of Aitziber) in Urdiain, San Martin de Ataun, Ondárroa, Ibarrangelua, Andra Marije de Guernica.

Churches built by Moors: Opacua and those in the surrounding villages, Zurbano, Oñate.

The bell tower and the bells in tradition: the ringing of the bells to ward off storms or hailstorms; to cure illnesses, mainly headaches; to ward off evil spirits.

Circling churches, cemeteries, and houses, a harbinger of misfortune, as is going out at night to settle a bet.

Circling churches to obtain some favor (in San Miguel de Ereñusarre, in San Vitor de Gauna, in Onraita, in Santa Agueda de Alonsotegui).

Procession of the dead around the church.

Custom of placing crosses and food on graves to light and feed souls in the afterlife (Berástegui, Cortézubi, Oyarzun, Andoain, Axpe).

Custom of burying children who died without baptism under the eaves of their houses (Cortézubi, Rigoitia, Berriatúa, Motrico, Mendaro, Arechabaleta, Zarauz).

Healing virtues attributed to certain objects, such as the chains of Theodosius in San Miguel de Excelsis, the cross of Azkorre (Salvatierra), the cross of Langarica.

Belief in the healing virtues of images of saints and sacred objects: the Virgin of the Rose (in Bermeo), Saint Lucy of the Goiburu hermitage (Andoain), Saint Lucy of Ermua (Llodio), Saint Lucy of the church of San Pedro (Vitoria), the korpuz-santa or mummy of the church of Rigoitia, Saint Christopher of Arrazua, Our Lady of Arrate in Eibar, Our Lady of La Antigua in Zumárraga.

Cases of animism and the power of sacred statues; such as that of San Gregorio de Ataun, of San Roque de Placencia, of Our Lady of Aránzazu, of Antigua in Zumárraga, of Antigua in Ondárroa, of Santiago in Astigarraga, of Santa Isabel in Ataun.

The theme of the sister Virgins, which appears in a legend of Our Lady of Aránzazu and is repeated in those of Guadalupe, of the Antigua of Zumárraga, of Ondárroa, of Kizkitza (Ichaso), of the Antigua of Lequeitio, of Orduña, of Andikona (Berriz), of Ujué, of Muskilda (Ochagavía), and of Arburua (Izal), is parallel to that of the Mari sisters of the underworld, perhaps inherited and copied from it.

Dancing in churches, such as that of Our Lady of the Ancient in Zumárraga and that of Oñate; in processions, such as that of July 2 in Ataun, that of Good Friday in Andoain, that of San Roque in Deva, and at the patron saint festivals in Oyón.

The cemetery and the church. Lights on the tombs and the cemetery encirclement.

Numerous themes have been developed in legends and tales, which we list below:

The man who raised a snake is killed by it. This theme is found in Ormazarreta (Aralar), Jentiletxeeta (Motrico), Ernio, Cortézubi, and Gorriti.

The snake that wants to test its strength with a man is defeated by the latter’s skill (Cortézubi).

A Gentile wants to test his strength with Christians and is defeated by the arts of one of them (Ataun).

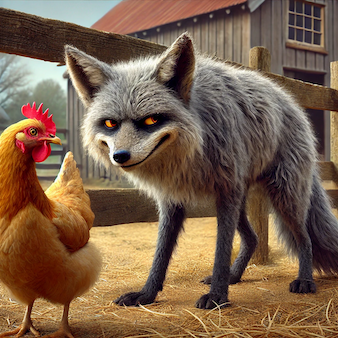

The wolf (or snake), rescued from a tight spot, wants to eat its liberator, but the latter is saved thanks to the cunning of a fox. A theme that covers a wide part of the world, from Scandinavia to the people of southern Africa, passing through Russia, Italy, and Greece (115. Aarne-Thompson: The Types of the Folk-Tale. FF Communications. No. 74, Helsinki, 1928).

The fox who shoes the squirrel with nutshells.

The three truths of the fox.

The thrush, the dove, and the fox in society (K 604, Stith Thompson: The thrush, the dove, and the fox in society. Motif-Index).

The fox who eats the crow’s young.

The fox steals cheese and sends the wolf to receive punishment.

The fox approaches the mill dog, who plays dead, and is devoured by it.

The tragedy of the fox who allows himself to be carried into the air by a vulture who releases him from above the clouds.

The fox who eats the egg omelet prepared for the threshers.

The fox, the wolf, and the moon reflected in a well.

The wounded wolf and the knight fox (3 and 4, Aarne-Thompson: The Types of the Folk-Tale, Helsinki, 1928).

The fox punished by an octopus.

The rooster, hunted by the fox, deceives him and is saved.

The fox loses his life due to the drizzle.

The donkey, caught by the wolf, manages to deceive him, claiming that he has to attend mass in a hermitage and, locking the door from the inside, is saved.

The lame donkey and the blacksmith wolf.

The man who aspires to fly and the vulture that carries him through the air and lets him fall.

A wager between the vulture and the wren, won by the latter.

The donkey, the dog, the cat, the rooster, and the ram, who leave their homes, settle in a robber’s den, punish the robber’s leader, and eat his dinner. A widespread theme throughout the world, with variations in Scandinavia, Germany, Flanders, Italy, Russia, and in the folklore of Missouri in America (Joseph Médard Carriére; Tales from the French Folk-Lore of Missouri. p. 19, Evanston and Chicago, 1937; 130, Aarne and Thompson: The Types of the Folk-Tale. A Classification and Bibliography.—FF Communications, no. 74. Helsinki, 1928).

The March thrush curses this month for its late snowfall.

The wolf cub and the young goat who gather laurel branches on Palm Sunday.

The geese in the wheat field.

The wolf who owns the forest eats the girl who did not obey him.

The fox who distracts Mari and drinks her milk in the meantime.

The sheep and the herbs that resist her.

The war of the animals and the fox, spy, punished by the bees.

Makillakixki or the donkey that makes gold, the table that produces delicacies, and the stick that punishes the thief.

The woman, persecuted by her mother-in-law, loses her hands and her children, only to miraculously recover them.

Legendary account of the life of Saint Genevieve of Brabant by the bertsolari Juan Cruz Zapiain.

Kastillopranko and the three labors imposed on the unfortunate gambler, who performs them with the help of one of his daughters.

Dar-dar, or the ogre who sucks and consumes a young woman’s fingers and is killed by her brother.

The dragon who devours a person every day, the hero who killed him, the charcoal burner who takes credit for this feat, and the latter’s punishment. All or several of these themes were collected by Vinson (Le Folklore du Pays Basque, 56) and by Webster (Basque Legende, p. 87). Their range is very large: we find them in ancient and modern Greece, the Caucasus, India, Japan, and the New Hebrides (Cosquin: Contes populaires de Lorraine, pp. 80-81, Paris, 1886; Anthropos, vol. X-XI, pp. 269-271).

Five extraordinary men who save the king’s daughter and are rewarded.

The three privileges that Juan Soldado requests: with one, he manages to capture the devil and expose him to the mockery and abuse of schoolchildren; he dies, and hell refuses to receive him.

Patxi the blacksmith and the three punishments he imposed on the devil; he dies, and hell refuses to receive him; he manages to deceive Saint Peter and enters heaven.

The king and the salt, or the test to which a king subjected his daughters; punishment

and triumph of the one he declared to be the salt of the world more necessary

than a king.

Cinderella; the scorn of her mother and sister; protection of the Virgin and marriage to the prince.

The fisherman who catches a fish that, in exchange for his freedom, promises him riches. Another day he catches the same fish again, which, in exchange for the one he encounters upon his return to port, promises him new riches. He is forced to give it to him, thinking that, as usual,

a little dog will appear on his path. But this time it is his son who comes to look for him, and he is taken to the house of the devil who appeared in the form of a fish.

The lion, the dove, and the ant, gratefully grant a man three privileges with which he succeeds in taking the lives of the devil and his brother from Iparrarremendi.

The little shoemaker who, with his powerful voice, frightens the giant and uses his strength to kill a dragon and save the king’s daughter.

The fortune-telling shoemaker and the discovery of the priest’s horse and the discovery of the king’s treasure, the thieves who stole it, etc.

The charitable little shoemaker and the hat that divined everything.

A child killed by his mother, eaten by his father, and resurrected thanks to his sister’s care.

Adventures of little Baratxuri in a cow’s stomach and in a donkey’s ear.

Students who receive money from the devil on condition that they guess what material a glass is made of.

Three brothers—one of them mad—who, climbing a tree, let a door fall on a group of thieves and seize their treasure.

The witch who transforms a young lady into a dove and impersonates her.

Three children bring firewood from the forest. Their mother gives them buns as a reward. Two of them, hard-hearted, do not help a poor man with their bread; the third does; he goes to heaven, the former to hell.

Juanillo the Bear and his companions: fight with the devil; liberation of the king’s daughter; magic ear.

Four orphans, one of whom became an astronomer, another a tailor, the third a hunter, and the fourth a thief. The four work together to free the king’s daughter, held captive by a dragon.

A young man whose calf is stolen; he shows up at the thief’s house, beats him with sticks, and charges him well over the value of the calf. He appears again disguised as a doctor, and finding himself alone with the sick man, beats him a second time; and charges more money, etc. (Cegama, Olaeta, Oyarzun, Nachitua).

The man who didn’t let his son be sponsored by God, but rather by Death, who makes everyone equal, rich and poor.

The doctor who saw death.

Two magic eggs and three garments: the hat that makes one invisible, the cape that takes one wherever one wants, and the bag that never runs out.

This first series of EUSKO-FOLKLORE ends with the description of the popular life of Saint-Esteben, a small village in Lower Navarre, which I published in Bayonne in 1941.

Themes of Eusko-Folklore, Second Series

The second series had its laboratory in Sara. The first four issues were published in the weekly Herria of Bayonne, and the remaining three in the IKVSKA newsletter. Various myths and legends relating to subterranean spirits appeared in the issues of this series, spirits that appear in the form of horses, bulls, cows, rams, lambs, sheep, goats, nannies, and snakes.

Ataun, December 1954.

José Miguel de Barandiaran

Share this / Partekatu hau:

Like this:

Like Loading...