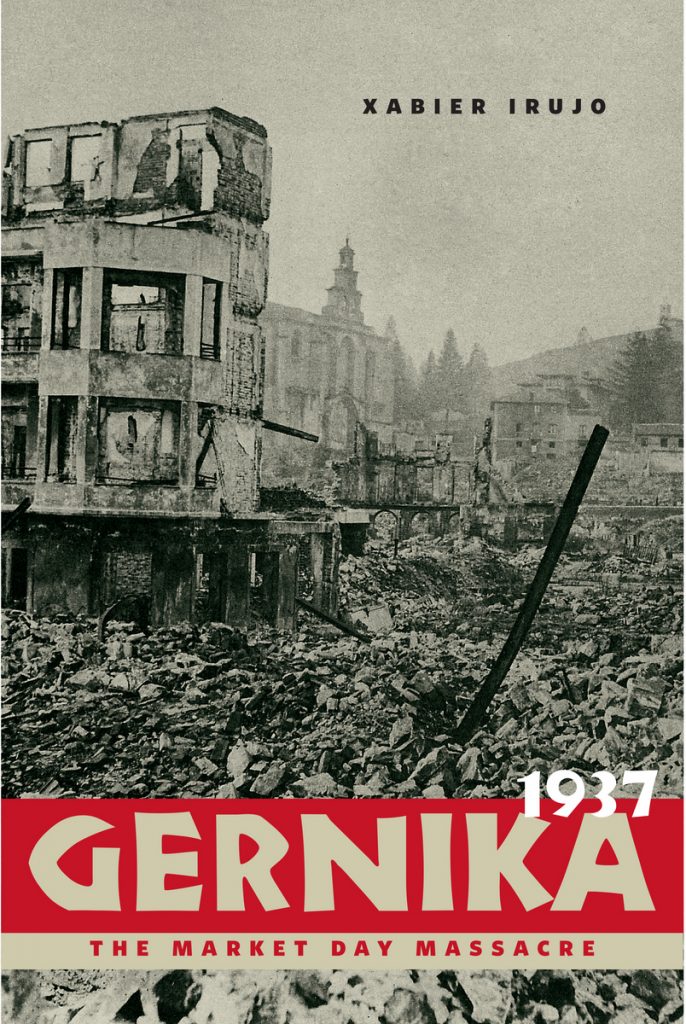

April 26, 1937. Market day in the Basque village of Gernika. Though the Spanish Civil War raged around them, villagers still gathered at the market. However, that day would come to live in infamy as the Condor Legion of Germany, at the behest of the Franco and his forces, bombed the symbolic Basque town. Not only did they bomb it, they strafed the fleeing populace. They planned an attack that maximized casualties and terror, avoiding the few strategic targets in Gernika, such as the factories, while destroying nearly every thing else. As the first civilian population that was bombed solely to inflict terror and maximize damage, Gernika has become a symbol of the horrors of war.

April 26, 1937. Market day in the Basque village of Gernika. Though the Spanish Civil War raged around them, villagers still gathered at the market. However, that day would come to live in infamy as the Condor Legion of Germany, at the behest of the Franco and his forces, bombed the symbolic Basque town. Not only did they bomb it, they strafed the fleeing populace. They planned an attack that maximized casualties and terror, avoiding the few strategic targets in Gernika, such as the factories, while destroying nearly every thing else. As the first civilian population that was bombed solely to inflict terror and maximize damage, Gernika has become a symbol of the horrors of war.

Of the three countries involved in the bombing — Spain, Germany, and Italy — only Germany has issued any statement of apology. During Franco’s dictatorship, Spain never even acknowledged that Gernika had been bombed by him and his allies, instead blaming the destruction on Basque “Reds” that burned the city for propaganda. Because of the denials and the lack of a consistent historical record, and as a consequence of new documents brought to light from a variety of sources, Xabier Irujo, in his book Gernika, 1937: The Market Day Massacre, details the evidence for both the involvement of those three countries in the bombing as well as the level of destruction it created.

Irujo’s analysis describes exactly how meticulously planned the attack was. According to Irujo, the German Air Force, lead by Hermann Göring, used the bombing as a demonstration of the power of an air force to inflict fear and terror on the populace. The goal was to show Hitler and the rest of the German military the might of the air force. As such, documents record various participants as saying that the mission was a complete success, even though the few military targets were not hit.

The number of casulties is still in dispute. The entry on the bombing at Wikipedia, for example, claims that while there was some exagerated claims in the past, recent consensus places the number of deaths at around 400 or less. However, Irujo argues convincingly, based on numerous eye-witness testimony and the structure of the bomb shelters in Gernika, that the number is significantly higher, more likely near the 1500 or more that was originally reported by the Basque government.

It seems remarkable that the facts surrounding such an event are in so much dispute. This is the true motivation of Irujo’s study, quantifying at every possible point the numbers associated with the bombing: the numbers and types of planes, the locations and capacities of all bomb shelters in Gernika, the attacks on neighboring towns before and after the bombing of Gernika (Gernika was not the first Basque town, nor Spanish town for that matter, to be bombed (my dad’s home town of Gerrikaitz was also bombed) but it was the first to be attacked in a manner to destroy the civilian population). At some points, the recounting of these numbers becomes a bit heavy, as the litany of facts distracts from the narrative of the bombing itself. But, these facts serve the vital role of precisely documenting exactly what is known about the bombing, as a counterpoint to those that would still downplay the events of that day.

The historical importance of events such as the bombing of Gernika cannot be lost. Particularly the context of the bombing, the Spanish Civil War, has uncanny parallels to our own time, in which proxy wars seem the norm. The Germans and Italians could deny involvement in the Spanish Civil War because the democratic powers wanted to avoid what was increasingly seen as an inevitable world war that would engulf all of Europe and beyond. Thus, they willingly turned a blind eye to what was going on in Spain, even though there were official policies, agreed to by all parties (Germany and Italy included) to not intervene. After the bombing, Nationalist forces quickly overtook Gernika and hid from the world all evidence of the bombing, making it nearly impossible for an accurate accounting. Feels eirily like multiple warzones in 2015.

In the end, Irujo does the world a service in detailing the facts about what is known about the bombing of Gernika, providing an updated historical record for future generations. Gernika, Dresden, Hiroshima… these cities represent the capacity for humanity’s destructive tendencies towards ourselves and must not be forgotten.

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Gernika, 1937: The Market Day Massacre”