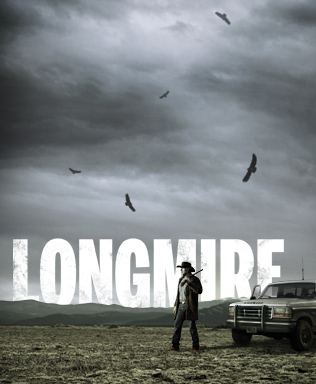

On June 10th, A&E broadcast the episode of Longmire that features the crew dealing with a Basque community in Wyoming, Death Came in Like Thunder. For those who missed it but are interested in seeing it, you can catch it on A&E’s website.

On June 10th, A&E broadcast the episode of Longmire that features the crew dealing with a Basque community in Wyoming, Death Came in Like Thunder. For those who missed it but are interested in seeing it, you can catch it on A&E’s website.

The plot centers around the murder of a Basque sheepherder, the grandson of Basques who lost the rest of their family in the bombing of Gernika. While investigating the murder, the cast of Longmire visit a Basque festival, in progress, and the scene that a bunch of Basques (and non-Basques) were recruited to lend authenticity — you can read about the actual filming experience here. They later find one of the sheepherders, brother of the dead man, in the mountains tending sheep and then go to the home of third brother. Throughout, various references to Basques are made with varying degrees of accuracy.

Overall, given the difficulty of both cramming in as much Basqueness as possible while still staying true to history, I felt they did an admirable job. They had the sheepherder and his dog featured in the beginning of the episode, with the herder sporting a big black beret. The star, Walt, tells Vic, the sidekick, that the Basques came to Wyoming to escape World War II. This is the first inaccuracy, as the reason Basques left Euskadi are more varied and more complex, but Basques in Spain weren’t directly affected by WWII. The Spanish Civil War, on the other hand, would have been more accurate. But, there were Basques in them thar hills before the war. And most of the Basques in Wyoming, I believe, are from the French side, so maybe they could have been escaping WWII, in principle. This didn’t bother me too much, actually, as it isn’t a documentary, but one character giving his explanation. As in real life, and as is true of many Basques themselves, he can be wrong. While investigating the cabin of the dead herder, they find a postcard of Picasso’s Guernica. Thinking on the date, Walt realizes that today is the day of St. Ignacio and there is a Basque festival (never mind that St. Ignacio’s feast day is in July and this episode is supposed to take place in the spring…).

The festival is an interesting mix of both big, Jaialdi-style festivals with booths for food, sport, nicknacks, and alcohol, but with a very small festival feel. They have the Basque colors everywhere and some traditional dress (the crew made the costumes for the women dancers). There really isn’t any dancing though — the dancers carry a hoop around but there is no dancing. I guess there wasn’t time for it. There are traditional sports: tug-of-war and orga jokoa, a game in which men lift wagons and turn them as much as they can. The filming showed relatively small guys lifting what were supposed to be 400 lb weights into the wagons. That didn’t make the cut, presumably because they realized there is no way the little guys could do that. Walt and Vic approach one of the food booths and Walt eats what is implied to be a

The festival is an interesting mix of both big, Jaialdi-style festivals with booths for food, sport, nicknacks, and alcohol, but with a very small festival feel. They have the Basque colors everywhere and some traditional dress (the crew made the costumes for the women dancers). There really isn’t any dancing though — the dancers carry a hoop around but there is no dancing. I guess there wasn’t time for it. There are traditional sports: tug-of-war and orga jokoa, a game in which men lift wagons and turn them as much as they can. The filming showed relatively small guys lifting what were supposed to be 400 lb weights into the wagons. That didn’t make the cut, presumably because they realized there is no way the little guys could do that. Walt and Vic approach one of the food booths and Walt eats what is implied to be a  Rocky Mountain Oyster (in reality it was a meatball). I haven’t ever seen one of those at a festival (though I have in my parents’ fridge) but it isn’t the kind of thing I would seek out either. Otherwise, the scene has people wandering, talking, drinking, and having fun, much like any real festival. The sausages were far from chorizo, but no one could see them anyways (you can barely make out that dashing cook preparing that fine fare). I thought they did a nice job with the festival.

Rocky Mountain Oyster (in reality it was a meatball). I haven’t ever seen one of those at a festival (though I have in my parents’ fridge) but it isn’t the kind of thing I would seek out either. Otherwise, the scene has people wandering, talking, drinking, and having fun, much like any real festival. The sausages were far from chorizo, but no one could see them anyways (you can barely make out that dashing cook preparing that fine fare). I thought they did a nice job with the festival.

Next we find Walt and Vic in the mountains, confronting one of the brothers. Of particular note here are the aspens with the arboglyphs, a well-documented feature of the Basque presence in the western mountains (though I think many cultures carved images into the trees). The herder describes how the arboglyphs recount their family’s history with the land and how the timber company wants to take their land and trees. (Here, my father-in-law, a former logger, pointed out that timber companies don’t want aspens, they are useless as lumber.)

Next we find Walt and Vic in the mountains, confronting one of the brothers. Of particular note here are the aspens with the arboglyphs, a well-documented feature of the Basque presence in the western mountains (though I think many cultures carved images into the trees). The herder describes how the arboglyphs recount their family’s history with the land and how the timber company wants to take their land and trees. (Here, my father-in-law, a former logger, pointed out that timber companies don’t want aspens, they are useless as lumber.)

This brother thinks the timbermen killed his brother so he fights them and gets arrested. While in jail, he describes how his grandparents’ families were killed in the bombing of Gernika. Walt then stares at the postcard of Guernica and recounts a poem by Norman Rosten, made into a song by Joan Baez, which has the phrase “death came in as thunder while they were playing” — hence the title of the episode. He then goes on to state how the Basques would always look someone in the eye when killing them, an odd reference indeed.

The final glimpse into the Basques occurs when Walt and Vic go to the third brother’s home. There is a painting on the wall, a painting that was done by a friend in Santa Fe. But, there isn’t too much said about the Basques in this scene.

The final glimpse into the Basques occurs when Walt and Vic go to the third brother’s home. There is a painting on the wall, a painting that was done by a friend in Santa Fe. But, there isn’t too much said about the Basques in this scene.

One last thing is worth noting. The two living brothers refer to the dead brother as “basati”, which means wild or savage in Batua. Not sure if anyone would use it in the context of calling their brother crazy or wild. Anyone know?

So, in the end, things weren’t perfect. Some things they got off a bit, particularly with the motivation for the festival, but, that said, I thought it was an overall very nice portrayal of Basque-Americans. It was refreshing to have a positive spin on Basques, even if it was at the expense of those evil timbermen (sorry Dave!), as opposed to crazy jumping warriors or the stereotypical terrorist. Of course, the time of the Basque sheepherder is nearing its end. Most sheepherders are now from South America, often from Peru (at least in the Treasure Valley of Idaho). Though Basques are still involved in the industry, they have often moved up the ladder and own the outfits. Still, this was a positive portrayal, one that I’m proud to have been a part of.

In addition to the photos in this post, I’ve put a gallery of some other screen captures from the episode here.