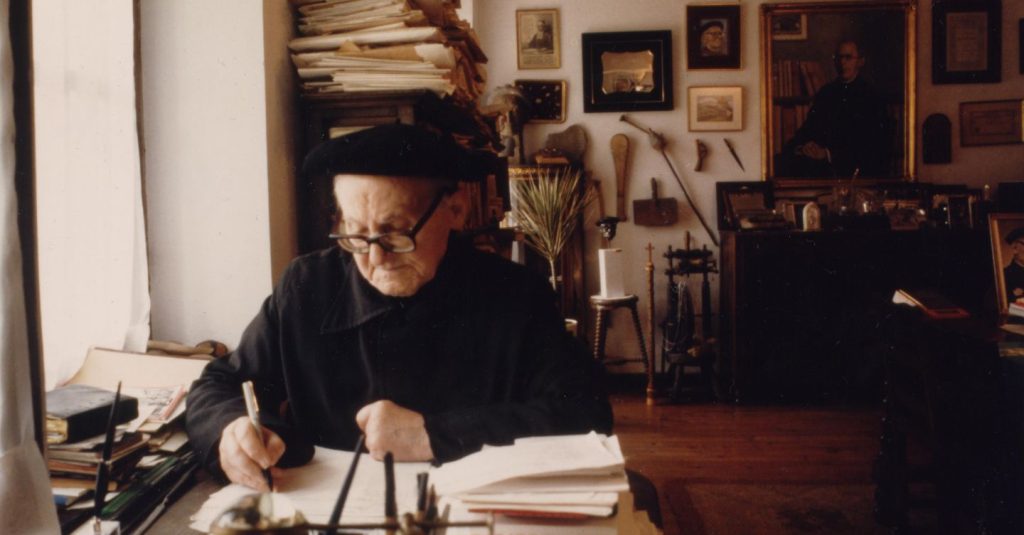

The Basques converted to Christianity relatively late compared to many of their neighbors, and before that they had a complex and fascinating mythology that involved a myriad of creatures and powerful beings that impacted the daily life of the people dotting the Basque coast. Much of what we know about that mythology – and Basque prehistory more generally – can be traced to the efforts of one man, a priest who grew up in the most modest of conditions: José Miguel de Barandiaran Ayerbe.

- Barandiaran was born in the Gipuzkoan village of Ataun on December 31, 1889 to Francisco Antonio Barandiaran and María Antonia Ayerbe. He was the youngest of nine children. He grew up in a world where Euskara was the language of the home and the street and Spanish was for rich and learned people. Remnants of mythological beings sprinkled the countryside. The children believed that lamia, basajaun, and tartalo used to roam the region. At the village school, the children were forbidden to speak Euskara. Whoever did, was given a ring. The ring passed to the next student to speak Euskara. At the end of the day, the child holding the ring would be punished.

- At the urging of his mother, he began studies to be a priest when he was 14, being ordained in 1914 at the age of 24. He joined the seminary of Vitoria-Gasteiz two years later as a science teacher, where he taught, amongst other subjects, physics and chemistry.

- Not long after becoming a priest, Barandarian began his ethnographic studies of the Basques and their culture. Barandiaran was extremely prolific, publishing a large number of articles and books over his career – nearly 250 in total. Of particular note is the large collection of Basque folk tales that he collected, often directly from the tellers, capturing their individual idiosyncrasies in each story. He also documented the daily life and the important dates in many towns of the Basque Country, providing an invaluable snapshot of Basque life.

- He worked closely with other prominent ethnologists, including Julio Caro Baroja, whom he mentored, his own mentor Telesforo de Aranzadi, and Enrique Eguren Bengoa. Together, Barandiaran, Aranzadi, and Eguren formed a particularly successful research team – sometimes called “the three sad cavemen” – that lead many of the prehistoric excavations in the early 1900s, beginning with the excavation of dolmens in the Aralar mountains. This discovery was inspired by local legends of the jentilak that were buried there.

- At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, in September 1936, Barandiaran went into exile. His work on Basque prehistory and ethnography was viewed suspiciously by those on the right, who connected it to separatist movements. He escaped to Iparralde, living first in Biarritz and then in Sara, Lapurdi, where he would remain until 1953, when he finally returned to Spain and took a position at the University of Salamanca. The three sad cavemen, separated at the beginning of the war, never saw one another again as Eguren died in 1942 and Aranzadi in 1945. During his exile, he received many offers to join other institutions, including Columbia University in New York, but he turned these down, expecting to return some day to Vitoria.

- Over his career, he enjoyed many recognitions for his work, including being a member of Euskaltzaindia (the Royal Academy of the Basque Language), serving as president of Eusko Ikaskuntza (the Society for Basque Studies), and receiving an honorary doctorate from Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (the University of the Basque Country).

- Barandiaran died on December 21, 1991, just 10 days shy of his 102nd birthday. He worked until the end, publishing Myths of the Basque Country in 1989 when he was 100.

Thanks to Jabier Aldekozea who inspired the title of this post.

Primary sources: The Jose Miguel de Barandiaran Foundation; José Miguel de Barandiarán, Wikipedia (Spanish); Jose Migel Barandiaran, Wikipedia (English); Estornés Lasa, Bernardo [et al.]. Barandiaran Ayerbe, José Miguel de. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/barandiaran-ayerbe-jose-miguel-de/ar-11007/

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wow, I had no idea about this guy!

Glad I could share something new!