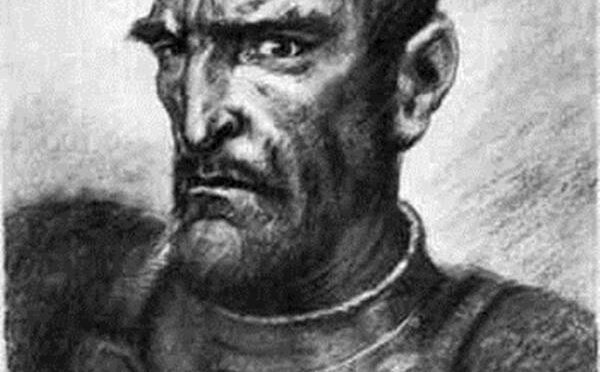

Women enjoy more opportunity now than they have for quite some time. With the rise of the Church and capitalism, women were marginalized, but before that, they held important role in professions such as health care. Martija de Jauregui wasn’t necessarily a pioneer – she just practiced her craft as she knew it. However, she was eventually forced aside despite the renown she had gained for her skills. Today she is viewed as an icon of women’s rights.

- Martija de Jauregui was born sometime in the mid 1500s, likely in Nafarroa, though next to nothing is known about her early life. Her grandfather, Dr. Cartajena, had been a doctor in Lekeitio, so possibly she was born in Bizkaia. In any case, by 1570 she is known to have been practicing medicine in Nafarroa, specifically in Estella and Pamplona/Iruña. By 1580, she was in Uharte-Arakile, having moved there with her husband, where she continued to practice medicine.

- Though she didn’t know how to read nor write, she had learned much about the practice of medicine from her grandfather and she specialized in women’s health. By special dispensation from the chief doctor of Pamplona, she was given permission to practice medicine in the region.

- Her remedies were primarily plasters and concoctions she made with local plants she gathered in places like the mountains of Aralar and had blessed in one of the churches during special fiestas such as San Juan. She also recommended masses and prayers to help alleviate symptoms and cure her patients.

- It was about this time that the Renaissance changed everything. Medicine became more professionalized and dominated by men. Women such as Martija were marginalized. Though she was well regarded for her medical prowess, she was eventually prosecuted by the Inquisition and medical professionals for effectively practicing medicine without a license or title and forced to abandon her profession.

- Today, as a woman who was cutoff from opportunities for schooling and practicing her profession, Martija is recognized as an icon of women’s rights. One of the giants in the festival of Uharte-Arakile is dedicated to her and she is featured in the Parque de las Pioneras in Pamplona.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Martija de Jauregui, Wikipedia; Martija de Jauregui, Wikipedia; Arozamena Ayala, Ainhoa. Jauregui, Martija de. Enciclopedia Auñamendi, 2024. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/jauregui-martija-de/ar-63803/; Martija de Jauregui, Mujeres que hicieron historia